El Alianza de Canal; Un organización para crecimiento generacional

March 31, 2022

Al Lado de carretera 101 y San Quentin Cresta, la zona del Canal de San Rafael alberga la más gran población de latinoamericanos e inmigrantes en Marin. Con más de 41, 713 residentes, COVID-19 tuvo un gran impacto en la comunidad y fue uno de los lugares con más casos de COVID-19.

Pero en este oscuro momento bancos de comida se abrieron, las pruebas de COVID-19 eran gratis y se ofrecía ayuda para encontrar trabajo, donaciones de dinero y asistencia para pagar el alquiler, un éxito que se puede atribuir en gran medida al Alianza del Canal. Creado en 1982 y actualmente bajo el liderazgo de Oficial Ejecutivo Omar Carrera, la Alianza del Canal es una organización activista y política que trabaja para romper el ciclo de pobreza en inmigrantes Latinos y sus familias. Además de su trabajo en respuesta a COVID-19 el programa tiene servicios para apoyar a residentes además de ayudar con viviendas asequibles.

“No puedo resolver las problemas del mundo pero puedo tratar de resolver las problemas en mi barrio o mi condado. [Y] eso es que [la Alianza de Canal] esta tratando de hacer.”

La cosa diferente de la Alianza del Canal respecto a otros programas es que como se dice en la declaración de objetivos, su objetivo es ayudar con el crecimiento a largo plazo y aliviar a corto plazo. Para Carrera el crecimiento a largo plazo es la educación.

“Families todavía tenían que pagar el alquiler y alimentar a sus niños, entonces nosotros tenemos programas diferentes que levantan las barreras hacia eso éxito … pero, lo que [El Alianza de Canal] cree como instituciones y como individuals, es que la educación es la manera mejor para conectar personas con oportunidades y trabajos de alta calidad [sostenibles],”

Para unos la educación significa adquirir habilidades lingüísticas. Para otros y especialmente ciudadanos Latinoamericanos de los EE.UU. que ya aprendieron inglés, la educación puede significar ir a una Universidad durante cuatro años. En esos casos, el Alianza de Canal tiene programas para después de terminar la escuela, programas de escuela y salud mental, y también dinero para becas para asegurar que todos tengan buenas oportunidades. Pero según Carrera, apoyar la educación no solo significa hacer una pasantía, sinó la oportunidad de obtener un trabajo o futuro sostenible.

“La economia ha cambiado. Todo ha cambiado con la automatización del trabajo que ocurre a un ritmo más rápido…duante la pandemia. Esto va a tener un impacto directo en los trabajadores de bajos ingresos. Debemos enseñar also a personas que va a desaparecer en cinco años a partir de ahora? No… necesitamos tener conversaciones para crear mas trabajos de alta calidad para garantizar que todos tengan la oportunidad de recuperarse de la pandemia. Necesitamos identificar las habilidades necesarias para trabajar y tener éxito en la economía posterior a la pandemia, y garantizar que estos nuevos empleos ofrezcan a los trabajadores beneficios, salarios dignos y la oportunidad de crecer.”

Este pensamiento metodológico es algo que la Alianza del Canal ha empleado en todos los niveles de su programación. Además de ayuda educativa y laboral, la Alianza del Canal también ha invertido en investigación sobre vivienda asequible para proporcionar viviendas de calidad y combatir la gentrificación. En su charla, Carrera dijo lo siguiente:

La crisis de vivienda no es única a Marin County, extende a través de el estado de california. Entonces la pregunta es que papel podemos nosotros tener en esto gran problema? Yo no pienso que debemos dejar la responsabilidad de resolver esto problema solo al gobernador o el presidente. Nosotros necesitamos reaccionar localmente … nosotros necesitamos proveer vivienda afortable donde personas pueden vivir con dignidad.”

Una iniciativa clave que Carrera destacó durante su discusión de la crisis de la vivienda es la necesidad de acción a nivel local.

Como organización no es sostenible que sigamos alquilando más espacio y contratando más empleados para responder a la alta demanda de servicios. Es por eso que también tenemos que trabajar en cambiar el sistema que está contribuyendo o creando el problema en primer lugar,” Carrera dijo, “Históricamente todas las políticas de vivienda que tenemos en nuestra ciudad y en este país son para segregar a las comunidades. La comunidad blanca ha tenido mucho éxito en segregarse con políticas de vivienda que impiden el desarrollo de complejos multifamiliares y protegen las viviendas unifamiliares. Esto ha contribuido directamente a la actual crisis de vivienda y la falta de diversidad en nuestras comunidades y escuelas en Marín.”

Carrera siguió enfocándose en las razones por las cuales el Canal fue tan afectado por el COVID-19 y fue porque el condado de Marin no estaba dispuesto a proporcionar viviendas asequibles en todo el condado. Esta idea fue reiterada por la Coordinadora de Extensión Legal Ilana Goldberg del departamento legal de la Alianza del Canal. Goldberg insta a la próxima generación de votantes a reevaluar y educarse sobre el legado de Marín y votar más allá de las elecciones estatales y nacionales.

“Si tienes casi dieciocho años, piensa en las elecciones y en quiénes son sus funcionarios electos, porque no puede cambiar la política federal a nivel local, pero ciertamente puede cambiar la política de aplicación de la ley [o las políticas de vivienda] a nivel local”, dijo Goldberg.

Hablando de la necesidad de trabajar en las políticas y la votación, tanto Carrera como Goldberg, argumentaron que los funcionarios electos a nivel local deben tener más atención.

“Cuando se piensa en el problema sistémico, realmente se remonta a tres cosas, ¿verdad? Políticos, políticas y personas que votan…Yo me convertí en ciudadano estadounidense en 2007 y he aprendido mucho sobre la historia de América. Para mi era muy interesante ver cuán desconectadas están las personas de las elecciones locales. Nadie conoce al alcalde, nadie conoce a los miembros del consejo de la ciudad, nadie conoce al fideicomisario de la junta escolar, o incluso a este supervisor del condado, porque siempre estamos pensando en las elecciones estatales y nacionales.”

The Canal alliance; An Organization For Generational Growth

Bordering Highways 101 and the San Quentin Ridge, San Rafael’s “Canal area” houses the most densely populated Latino and immigrant community in Marin county. With more than 41,713 residents, the Canal was hit particularly hard during the COVID-19 pandemic, quickly becoming Marin County’s largest hotspot for Covid-19 cases.

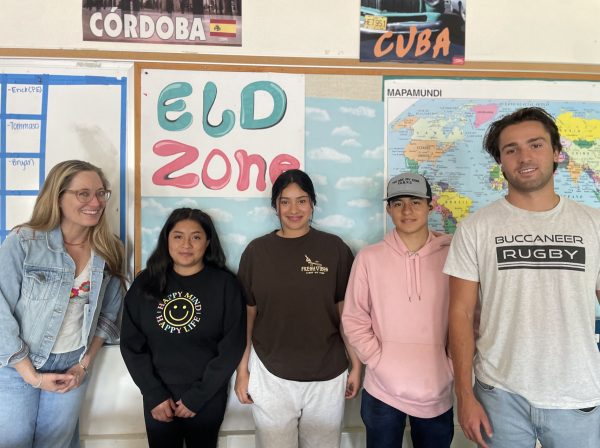

Yet in this moment of darkness, food bank distribution sites stayed open, free Covid-19 tests were provided, and financial, unemployment, and rental assistance was made available; a success that can largely be attributed to the Canal alliance. Created in 1982 and currently under the leadership of Executive Officer Omar Carrera, the Canal alliance is an activist and policy organization which aims to break the generational cycle of poverty for Latino immigrants and their families. Beyond its response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the program notably provides legal support to residents, in addition to affordable housing complexes.

“I can’t solve the problems in the world, but I can try to solve the problems in my neighborhood or my county. [And] that’s what [The Canal Alliance is] trying to do.

What differentiates the Canal alliance from other programs as it’s laid out in the programs mission statement, is its dedication to fostering long-term growth along with short-term relief. To Carrera, long-term growth means education.

“Families still have to pay the rent and feed their kids, so we have different programs that lift the barriers towards that success … but, what [the Canal Alliance] believe as institutions and as individuals, is that education is the best way to connect people with opportunities and [sustainable] high quality jobs,”

While for some, education may mean acquiring language skills. For others, and especially U.S. Latino citizens who have already learned English, education can mean a four year college degree. In those cases, The Canal alliance provides after school programs, academic and mental health support as well as scholarship money to ensure the best opportunities are given to people. But, according to Carrera, educational support for the U.S. Latino citizen youth from the Canal alliance, cannot end with college; for a college degree does not necessarily mean an internship, potential job opportunity, or sustainable future.

“The economy has changed. Everything has changed with job automation happening at a faster pace … during the pandemic. This will have a direct impact on low-income workers. Should we be teaching people now something that might disappear in five years from now? No … we need to broaden the conversation about how we can create high-quality jobs to ensure everyone has a chance to recover from the pandemic. We must identify the skills needed to work and succeed in the post-pandemic economy, and ensure these new jobs offer workers benefits, living wages, and the opportunity to grow,” Carrera said.

This forward and methodological thinking is something that the Canal Alliance has employed on every level of its programming. In addition to educational and job-outreach efforts, the Canal Alliance has also invested in affordable housing landscape feasibility research in an effort to provide quality homes to residents and combat gentrification. In his discussion of the study, Carrera said the following.

“The housing crisis is not unique to Marin County, it extends throughout the State of California. So the question is what role can we play in this big problem? I don’t think we should leave the responsibility of solving this problem solely to the Governor or the President. We need to respond locally … We need to provide affordable housing options where people can live with dignity.”

One key initiative emphasized by Carrera during his discussion of the housing crisis, was the significant need for policy action at the local level.

“As an organization it is not sustainable that we continue to rent more space and hire more employees to respond to the high demand for services. That’s why we also have to work on changing the system that is contributing to or creating the problem in the first place,” Carrera said, “Historically all the housing policies that we have in our cities across the county, are policies that contributed to segregating communities. For instance, the white community has been very successful in segregating itself with local housing policies that have prevented the development of multi-family complexes. This has contributed directly to the current housing crisis and lack of diversity in our communities and schools in Marin.”

Carrera went on to emphasize that the reason why the Canal was so disproportionately affected by the Covid-19 pandemic was because of Marin’s unwillingness to provide affordable housing across the county. This understanding of the cascading effects of local housing policies was reiterated by Legal Outreach Coordinator Ilana Goldberg, from the Canal Alliance’s legal department. Goldberg urges the next generation of voters to reevaluate and educate themselves on the legacy of Marin and voting beyond the state and national elections.

“If you’re nearly 18, think about elections and who your elected officials are, because you can’t change federal policy on a local level, but you certainly can change law enforcement policy [or housing policies] on a local level,” Goldberg said.

Speaking on the necessity of policy work and the vote, Carrera, like Goldberg, argued that elected officials, at the local level, should be at the top of mind.

“When you really unpack the concept of systemic problem, it really goes back to three things, right? Politicians, policies, and people who vote … I became a US citizen in 2007 and have been learning a lot about American history. For me, it was very interesting to see how disconnected people are from the local elections. No one knows their Mayor, no one knows their city council members, no one knows their school board trustees, or their county supervisor, because we are always thinking about state and national elections … [vote for those who] impact the lives of residents on a daily basis.”