Nuestra generación exige cambios: ¿vale la pena?

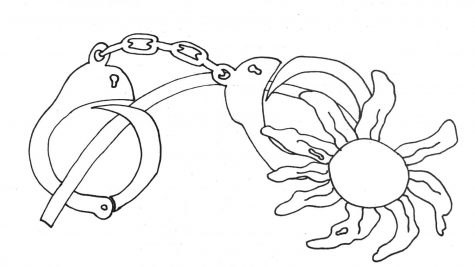

Personas gritando en las calles, pósteres soplando en el viento, pies marchando por el cambio. Protestas son comunes en nuestra generación. Ya sea sobre corrupción en el gobierno, el cambio climático, la seguridad del arma o cualquier cosa––salimos a las calles. ¿Pero para qué? Tenemos nuestro impulso y nuestras motivaciones, ¿pero puede una protesta realmente crear un impacto significativo? Creo que sí. Me gustaría esperar eso, por lo menos.

Las protestas son una parte importante para lograr el cambio, pero solo funcionan si una gran parte de la población está involucrada y si es pacífica.

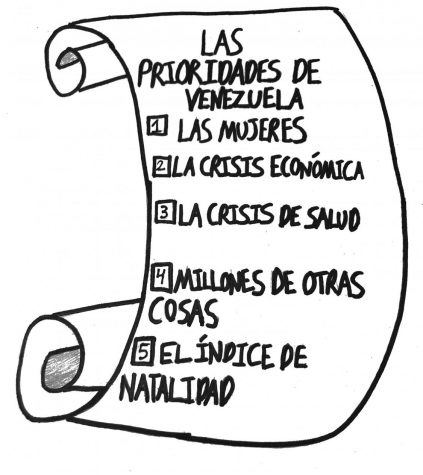

Como probablemente has escuchado en las noticias, ha habido una gran cantidad de protestas en Latinoamérica y alrededor del mundo este año. De Brasil a Chile y de Venezuela a España, estas protestas han tenido diferentes niveles de éxito por muchas razones.

En Brasil, por tres meses, los brasileños salieron a las calles, marchando contra el presidente Jair Bolsonaro y los incendios aconteciendo en el Amazonas. Muchos de los manifestantes culparon a Bolsonaro por los incendios porque quería desarrollar el Amazonas y explotarlo. Si eso es verdad o no, la selva más grande del mundo estaba quemando y algo necesitaba a cambiar. ¿Pero qué hicieron estas protestas? Nada. En cuanto estaban protestando, Bolsonaro salió a la televisión para decir que todo estaba bajo control. No quería la ayuda de otros países en el Cumbre del G7, y solo habló de su “amor por el Amazonas.” Si realmente amara a la Amazonía, habría hecho todo lo que está en su poder para evitar que los fuegos ardan, incluso si eso significa pedir ayuda de otros.

¿Por qué no funcionaron estas protestas? El cambio climático es una causa digna. No fueron violentas, simplemente pararon y bloquearon unas calles en ciudades grandes. Lo único que les faltaba: el poder de la gente.

Según las investigaciones de Erica Chenoweth, un politólogo en la Universidad de Harvard, “ningún gobierno puede soportar un desafío del 3.5 por ciento de su población.” Si tomas eso en consideración, aproximadamente siete millones de brasileños necesitaban protestar para que fuera exitosa. En realidad, solo unos pocos miles protestaron en ciudades grandes como São Paulo y Rio de Janeiro; mostraron el sentido de la gente pero no obligaron al gobierno a hacer cambios.

Más reciente que eso, en Chile los ciudadanos de clase media empezaron a protestar en el comienzo de noviembre contra un impuesto en la transportación pública. Después de dos días de protestas violentas, el gobierno canceló el impuesto. Pero no fue el fin de los problemas en Chile. Los manifestantes continuaron protestando en formas violentas contra las desigualdades en la economía.

Aunque la problema inicial fue resuelta con la violencia, dudo que el desafío más grande con la economía total va a ser concluido en esta forma. Según las mismas investigaciones de Chenoweth, protestas violentas solo funcionan 26 por ciento de las veces y protestas pacíficas son exitosas 53 por ciento de las veces. Midieron el éxito según si el gobierno reconoció o no las protestas e hizo cambios.

Además, según el Centro Internacional de Conflictos No Violentos, “los levantamientos no violentos son casi tres veces menos propensos que las rebeliones violentas a enfrentarse a asesinatos en masa,” y las protestas violentas enfrentan una represión tan brutal casi el 68 por ciento de las veces.

Si estos patrones de violencia continúan como están en Chile, pueden dar lugar a más consecuencias para los manifestantes y, obviamente, ese no es el objetivo. El objetivo es generar cambios, promover reformas sociales y políticas.

Nuestra generación tiene un impulso tan fuerte y necesitamos usarlo para nuestra ventaja en lugar de desperdiciarlo en emprendimientos desesperados. Al maximizar los efectos de nuestras protestas, podemos obligar a nuestros gobiernos a hacer los cambios necesarios para nuestros propios futuros.

English Version:

Our generation demands change: is it worthwhile?

People yelling in the streets, posters waving in the wind, feet marching for change. Protests are common for our generation. Whether it be about government corruption, climate change, gun safety or anything else, we take to the streets. But for what? We have our drive and our motivations, but can a protest really create a significant impact? I think so. I would like to hope so, at least.

Protests are an important part in bringing about change, but they only work if a significant part of the population is involved and if it is nonviolent.

As you’ve probably heard in the news, there have been a huge number of protests in Latin America and across the world this year. From Brazil to Chile and from Venezuela to Spain, these protests have had varying levels of success for multiple reasons.

To start with Brazil, it’s been three months since the Brazilian people took to the streets, marching against the president Jair Bolsonaro and the resource situation in the Amazon. Many of the protestors blamed Bolsonaro for the forest fires, because he wanted to develop and exploit the Amazon. Whether this is true or not, the world’s largest rainforest was burning and something needed to change. But what did the protests do? Nothing. While they were protesting, Bolsonaro appeared on television to say that everything was under control. He didn’t want help from countries at the G7 Summit, and only spoke about his “love for the Amazon.” If he really loved the Amazon he would do everything in his power to stop the fires from blazing, even if it meant asking for help from others.

Why didn’t these protests work? Climate change is a worthy cause. The protests weren’t violent, they simply stood and blocked some streets in large cities. The one thing they lacked: the power of the people.

According to the research of Erica Chenoweth, a political scientist at Harvard University, “no government can withstand a challenge of 3.5 percent of its population.” If you put this into account, approximately seven million Brazilians needed to protest in order for it to be successful. In reality, only a few thousand people protested in cities like São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro; they may have expressed the beliefs of the general public, but they did not compel the government to make changes.

More recently than this, in Chile, middle class citizens began protesting at the beginning of November against a tax on public transportation. After two days of violent protesting, the government cancelled the new tax. But this wasn’t the end of problems in Chile. The protesters continued violently protesting against the economic inequalities in the country.

Although the initial issue was resolved with violence, I doubt the greater challenge will be concluded in this form. According to the same research from Chenoweth, violent protests only work 26 percent of the time and nonviolent protests are successful 53 percent of the time. They measured success by whether or not the government acknowledged the protests and made changes.

Also, according to the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict, “nonviolent uprisings are almost three times less likely than violent rebellions to encounter mass killings,” and violent protests are faced such brutal repression nearly 68 percent of the time.

If these patterns of violence continue how they are in Chile, they may result in further consequences for the protestors and that is obviously not the goal. The goal is to generate change, to promote social and political reform.

Our generation clearly has such a strong drive and we need to use it to our advantage rather than waste it on hopeless ventures. By maximising the effects of our protests, we can force our governments to make the changes necessary for our own futures.

Sophia Rocha is a senior at Redwood High School and one of the Review Editors for the Bark. She runs varsity track and enjoys doing community service in...