Struggling for Survival: Bay Area sea lions face changing conditions

By Catherine Conrow and Macrae Sharp

Although sea lions can be spotted at beaches along the California coast, many of these marine mammals will end up in our backyard, 15 minutes away in Sausalito. Upon entering the Marine Mammal Center, a veterinary research hospital, seals and sea lions bark loudly as they are fed sardines in the form of “fish milkshakes.” It is here that a group of baby seals are learning to properly feed before being released back into the Pacific Ocean.

The Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito has seen a drastic increase in the number of starving and abandoned California sea lion pups in the past two years, according to Courtney Good, guest experience coordinator at the center.

The majority of the current sea lions at the center are pups who are younger than a year old and have been abandoned by mothers who left them in search of food, according to Good.

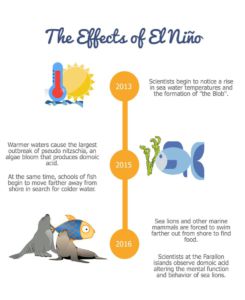

“Those fish are moving to colder and deeper waters, so then you have starving pups that are stranded on the shoreline because they cannot find the fish that they need to eat,” Good said.

There have been four times as many sea lions found stranded along the California coastline in Jan. and Feb. 2016, as compared to the average from 2003-2012, according to the center’s website.

“Every time there is an El Niño, we see a disruption in where the nutrients are because there is warm water in places where it is usually cold, so there are more algae blooms and so there are more fish in those areas,” she said. “The Marine Mammal Center starts to see animals that it doesn’t normally see, like Guadalupe fur seals and Northern fur seals.”

The presence of the El Niño weather patterns has caused a warm body of water that moves through ocean currents, a phenomenon referred to as the “Blob” by scientists.

Although “the Blob” is only 3-5 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than surrounding waters, the temperature increase can have drastic effects on small fish.

Due to this lack of fish and the increase of poor food quality, female sea lions are also aborting their fetuses at an almost exponentially increasing rate, according to Russell Bradley, senior scientist and Farallon program leader for Point Blue Conservation Science, a nonprofit research center located in Petaluma.

Furthermore, under normal conditions, mother sea lions usually deliver their babies during the summer. This year, however, sea lions were already giving birth by the end of March, according to Bradley.

The warm water of the Blob is also more hospitable to harmful algal blooms, according to Sharon Melin, who researches the health impacts of algal toxins on marine mammals at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The largest algal bloom yet of pseudo nitzschia, a diatom that produces domoic acid, was reported in 2015, according to Melin.

Domoic acid is a biotoxin that, with exposure, affects the brain and causes animals to become disoriented and lethargic, and sometimes even have deadly seizures, according to the Marine Mammal Center’s website.

Domoic acid contaminated much of the foraging fish stocks—Northern anchovies and sardines—that California sea lions usually eat in large amounts, senior research scientist William Cochlan wrote in an email. Cochlan is a biological oceanographer and a marine microbial ecologist at San Francisco State University, and he has published research on these recent harmful algal blooms along the West Coast.

“The contamination of the food web with domoic acid was the biggest we’ve seen yet, and so we’ve seen a lot of toxins in the marine mammals,” Melin said.

According to Melin, she and her team are working with the Marine Mammal Center to research domoic acid toxin samples and investigate the associated health effects on marine mammals.

“This would have caused some of [the sea lions] to die or become sickened due to the ingestion of this neurotoxin. Perhaps that contributed to their inability to find food to sustain themselves, as it affects both movement and short-term memory,” Cochlan said.

Researchers at the Farallon islands have also found domoic acid to significantly alter the mental function and behavior of sea lions, according to Bradley.

“The toxin makes the sea lions do strange things, like crawl up on the island a lot higher than they normally would or they just seem to make strange decisions,” Bradley said.

Although the productivity of the marine ecosystem has decreased due to the recent rise in ocean temperature, Bradley is hopeful that the negative trends will reverse due to high winds that blew through the California coast from the northwest. Bradley said he hopes that the winds will bring down sea temperatures and create a marine ecosystem that is better able to support marine life.

“We are seeing a lot of negative impacts now, but we are in this very critical period. If the ocean becomes cooler and if we even get a few strong pulses of productivity, it could turn the tide and improve things greatly,” Bradley said. “The timing of these events are crucial.”

Despite Bradley’s hope that sea temperature levels will drop, the Marine Mammal Center is continuing to see an influx of severely malnourished animals, such as the sea lions, coming to the hospital.

Junior Lindsay Thornton, who volunteers weekly at the Marine Mammal Center, said that the feeding routine for the sea lions in rehabilitation is important so that they will not adapt to being fed by humans, but rather learn to rely on natural instinct.

“I’ve noticed that [the pups] come in really, really skinny and emaciated. It’s really sad seeing their ribs,” Thornton said. “Especially the elephant seals, they come in really lethargic.”

Today, four types of marine mammals are housed at the Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito: California sea lions, elephant seals, Pacific harbor seals and fur seals.

On March 20, there were 73 California sea lions and 32 elephant seals at the Marine Mammal Center. The center has a capacity for 225 animals, and is currently hosting approximately 130 patients.

Many of the sea lions at the center were transported to the Bay Area by volunteers instead of swimming up the coast, themselves as they instinctively do, according to Good.