Marin City & the test of time

Individual persistence and community resilience

February 10, 2023

Seven courts, six drives, four streets, two circles and one avenue. A single road, Donahue Street, leads off Highway 101 and into the city, curving behind the shopping center that holds Target and Panda Express. Turn left at Phillips Drive, where Bayside Martin Luther King Jr. Academy and the Recreational Center greet you, and loop along Drake Avenue. Golden Gate Village, one of Marin’s largest affordable housing developments, sits nestled in the hills, and, if you continue past it on Drake, it’s only a minute until the highway stares back at you again.

Created 80 years ago during World War II, Marin City has remained resilient through struggles over segregation, housing and gentrification. But more than that, Marin City is a tight-knit and intergenerational community with an incredible history and promising future. Stemming from its wartime origins, continuous development and ongoing activism, Marin City’s evolving legacy is just its beginning.

Marin City was our playground. We used to go up to what’s now the Marin Headlands and play in the orchards…It was a fun community to grow up in — a very free-spirited kind of community. — Bettie Hodges

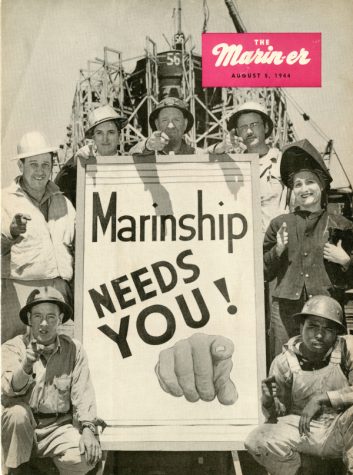

Marinship

Lifelong Marin City resident Bettie Hodges has lived through the history of Marin City first hand. Hodges’ parents, like many of Marin City’s first residents, moved to Marin from Mississippi during World War II to work in Marinship, a shipyard built in Sausalito that supported the U.S. war effort.

“When I grew up, Marin City was still the temporary wartime housing project that was built during Marinship to house 5,000 shipyard workers. It was the first integrated housing project in the whole country,” Hodges said.

Between 1940 and 1960, 3,348,000 Black Americans left the South in the Great Migration. A handful joined Marinship to work alongside Asian Americans and other minority groups, along with white workers, motivated by a sense of patriotism and labor opportunity.

“Most of our neighbors had come from the South, and they didn’t want to go back; they wanted to make Marin County their home,” Hodges said.

With such an influx of workers, Marinship faced severe housing inadequacies and turned to the Federal Housing Authority, who took control of the land north of Sausalito and built temporary homes, thus founding Marin City.

“It was the kind of neighborhood where we never locked our doors when we were kids,” Hodges said. “Marin City was our playground. We used to go up to what’s now the Marin Headlands and play in the orchards. The hill, [overlooking the city], was our slide and go-kart hill. We would climb up and spend the day sliding down on cardboard. It was a fun community to grow up in — a very free-spirited kind of community.”

Marin City, known at the time as the best-integrated shipyard in the West, still faced challenges in preserving its unique multicultural makeup. According to Felecia Gaston, the founder of Marin City’s Historical and Preservation Society, Marinship’s internal racial tensions drove a pro-integration labor movement.

“Marinship had what they called a Boilermakers Union, and [it] wanted all the Blacks to be in a separate auxiliary,” Gaston said. “Joseph James was a welder but also a famous performer who had been in several operas and plays back East. When he got the call to work, like many people, [he was] patriotic, so he came out here. He was the instrumental person who led the fight so that the Blacks did not have to be in a separate union, and it [eventually] became a California Supreme Court case.”

Joseph James v. Marinship encapsulated the nationwide equity issues of its era, although the case is seldom discussed in the rest of the county today. History and ethnic studies teacher David Minhondo was especially captivated by the case’s significance in American history, but also disappointed in how little recognition it has received.

“The fact that this one former Broadway worker moved [to Marin City] in the Second Great Migration [and] led this landmark California Supreme Court case [is incredible],” Minhondo said. “But then to find that it was also led by the famous lawyer, Thurgood Marshall, was like unraveling this thread that I thought would be a simple story and ended up being this civil rights victory, 10 years before Brown v. Board [of Education], that happened right here in predominantly white Marin County.”

James v. Marinship was one of Marshall’s first cases. Marshall would later become the first Black supreme court justice. It set a precedent throughout the state of equal opportunity in the workplace. This past summer, Marin City 80, a yearlong celebratory movement of the community’s 80th anniversary, developed a production detailing and commemorating James’ life in the play, “The Spirit of Joseph James.”

Likely encouraged by James and Marshall’s win, at its peak, a third of Marinship’s workforce consisted of minorities.

Marinship was incredibly successful in its operations: over the course of the shipyard’s three-and-a-half years effort around 93 vessels were built. After World War II ended, Marinship was decommissioned in May of 1946.

Redevelopment

Marin City was integrated when I grew up, but by the time I got back from college, it was [around] 70 percent Black because whites were able to move out of the community and purchase homes in various places in Marin County, and Blacks weren’t. — Bettie Hodges

“When Marinship was over, Marin City was slated to be torn down, so a group of residents got together to try to organize the redevelopment of Marin City,” Hodges said.

In conjunction with county supervisors and, eventually, a redevelopment agency that was granted by officials in Washington D.C., Marin City residents fought to save the community and continue their wartime economic prosperity.

Yet, the county was slow to update the city. In tandem with poor redevelopment efforts, Marin City also faced a new, post-war reality.

“Marin City was integrated when I grew up, but by the time I got back from college, it was [around] 70 percent Black because whites were able to move out of the community and purchase homes in various places in Marin County, and Blacks weren’t,” Hodges said.

Marin, like most suburbs post-World War II, allowed for practices of redlining and restrictive covenants — statements written into property documents that excluded people of certain racial identities from occupying homes.

Thus, while many parts of Marin began advertising as suburbia (coined “Marvelous Marin”), Marin City was one of the only available areas in the county where non-white people could live.

For the past two years, Crystal Martinez, an aide to Marin District Two supervisor Katie Rice, has closely examined these local housing injustices for the Marin County Restrictive Covenant Project, an initiative aiming to educate local residents of the intentionally discriminatory practices that helped segregate Marin. She explored how white communities had access to housing at historical low prices post World War II, allowing them to purchase homes that became highly valued in Marin County.

“Over time, these homes resell for a lot of money, [and] sometimes they’re kept in the family, so white families that stayed here were able to develop legacy wealth,” Martinez said. “By contrast, in Marin City, there weren’t as many single-family homes built, and certainly not with the purpose of selling to Black families. [Instead], public housing was built, and [the community] didn’t get to take much advantage of property taxes in the school district.

“So you see the lack of legacy wealth, and the lack of investment [in public resources] and the amenities that ‘Marvelous Marin’ [touted] for the rest of the county. And you saw that families [in Marin City weren’t] always able to remain in public housing, [they] didn’t get to say, ‘Now when I pass away, I bequeath my child my rental;’ that’s not how that works, right? People either had to leave, or stayed in conditions that [weren’t] as set up for success as they [were] in other spaces in the county.”

Consequently, Marin City’s evolution followed a different trajectory than other parts of Marin, eventually redeveloping — but into isolation, as it consisted largely of low-income housing.

New public housing was built in the 1960s, including Golden Gate Village: 300 units of housing that remain today as one of the only entry points for low-income families to live in Marin. Since then, the community has withstood decades of continued displacement on top of other inequities from gentrification, private development, and in particular, underinvestment in education.

Next Generation

Marin City and Sausalito were once home to two K-8 schools: Bayside MLK Jr. Academy and a charter school, Willow Creek Academy. While Willow Creek performed better academically and mainly taught Sausalito students, Bayside suffered from a lack of funding and primarily served Marin City residents.

Orianna Vaughn, whose great-grandmother migrated to work in Marinship, attended Bayside herself and witnessed firsthand the educational gaps when compared with her sister, who attended Willow Creek. Through her attendance at Bayside MLK and her transition to Tamalpais High School, those observed inequities became experiences for Vaughn.

“[In Advanced Placement courses], there was a disconnect in how my peers who were not Black and not from Marin City were performing and how I was performing … in terms of how my peers responded to the teacher, how they spoke and how they wrote. [For instance], I didn’t know what an annotation was — I [had] never learned,” Vaughn said.

Vaughn was not alone in her experiences. In fact, because of these disparities, in 2019, the Sausalito Marin City School District received California’s first school desegregation order in 50 years, a stark reverse from being the first integrated housing project in the country during World War II.

Vaughn is currently a teacher at Women Helping All People Scholastic Academy in Marin City, a school open to low-income children of color struggling in mainstream education. Many of her students transferred from Bayside in the past couple years.

“[Students are] defeated before the day hits 10 a.m. [They say], ‘Oh, well, I didn’t go to Willow Creek. I went to [Bayside], [the] stupid school, and I’m just stupid, and maybe if I had gone to Willow Creek, I’d be a lot smarter,’” Vaughn said.

Bayside and Willow Creek have been integrated campuses since 2021, though the process was not easy, with both schools’ students’ learning and comprehension suffering as a result. However, slowly but surely the school district is rebounding, becoming a unified community once again.

“Though I’m not in the classroom at Bayside MLK, I do have friends there and they say things are a lot better. [They’ve] made some tremendous changes that seem to be more positive this year than last year,” Vaughn said.

Retelling and Reshaping

Beyond education, persistent efforts from community leaders have allowed Marin City to find growth and empowerment throughout the decades.

educational and social opportunities. (Photo courtesy of Bettie Hodges)

Hodges, who worked with the Marin City Community Development Corporation to head economic development and introduce permanent housing, eventually founded the Hannah Project in 2007 to help first-generation students in Marin City navigate the college admissions process.

For Gaston, the future is about making the community’s history more visible. She’s collected newspaper clippings and oral histories of the residents in Marin City for decades, chronicling the narratives that often go unnoticed.

As one of the leaders of Marin City 80, an exhibit and celebration of the 80 years of Marin City, Gaston helped design an exhibit at the Bartolini Gallery this summer highlighting Marin City’s history.

“The telling of the experiences of Black people [in this county] was just hidden, lost stories that got out in bits and pieces, but never in a consistent way. That’s why the [Marin City 80] exhibit was so important,” Gaston said. “I have another publication that’s coming out soon [covering] 1942 to 2022 that’s really going to share [Marin City’s] history, the Black experience and also share through adversities and outside influences how the community has been resilient.”

Similar to Gaston, Hodges described a new goal that the entire community is striving to achieve: having every child be able to read in the third grade, while she continues to head the Hannah Project and the summer Freedom School.

Vaughn has plans to open up a bookstore for Marin City, envisioning a space where kids can go to be productive and creative. She sees the beauty that Marin City offers and hopes, with new projects and initiatives, the community will shine brighter than ever.

“[Marin City] has a lot of problems, but underneath, and what many don’t see, is that there are a handful of people, both young and old, who are collaborating to make Marin City a thriving and robust community,” Vaughn said. “It just takes time and money, and it takes faith. So as long as you have people who aren’t willing to give up on it and on the kids, and you have allies who are willing to lend a helping hand, it will get better — it is getting better.”