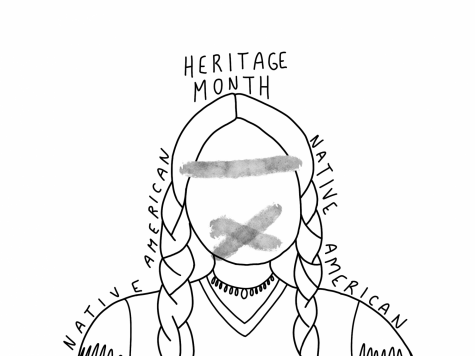

November: The month to face the reality of Native American oppression

December 14, 2021

The month of November is often associated with Thanksgiving celebrations and fall festivities; now, as of Oct. 29, 2021, November is “Native American Heritage Month.” President Joe Biden, the third president to implement this title, aims to celebrate and honor the lives of Native Americans, specifically American Indian and Alaska Native (AAIN) people. Although this acknowledges the often forgotten history and culture of Native Americans living in the U.S., it does nothing to stop the widespread mistreatment and oppression of these individuals that continues to prevail.

AAINs are one of the most marginalized minorities today in the U.S. Their history of oppression began in 1492 when Christopher Columbus “discovered” the Americas, only to conduct a mass genocide on the Native Americans that already lived there. These individuals not only had their land stripped from them, but they also lost their traditions, culture and values, as a result of land-hungry, white colonizers. Although we have since realized that the “peaceful” Thanksgiving dinner between the Native Americans and Pilgrims — a topic first introduced in kindergarten — was a falsity created to conceal a tragic history, the reality is that the disparities that they faced still lie in our country today.

A study done by First Nations in 2019 revealed that two-thirds of Americans do not believe that Native Americans experience significant racial discrimination. While this is clearly a common belief across the U.S., the reality is that Native women are 2.5 times more likely to be raped or sexually assaulted than any other ethnic group, and 97 percent of Native Americans have experienced violence perpetrated by at least one non-Native person.

Despite AAINs only making up about 2.9 percent of the U.S. population, they still face these extortionate rates of discrimination. For instance, according to the Indian Health Service, AAINs have a life expectancy of 5.5 years less than any other race in the U.S. In addition, they die at higher rates than any other race due to various diseases along with assault, homicide and intentional self-harm.

These disparities show the prevalence of discrimination towards Native Americans, which raises the question: why is this reality not further acknowledged and how is there not enough action taking place?

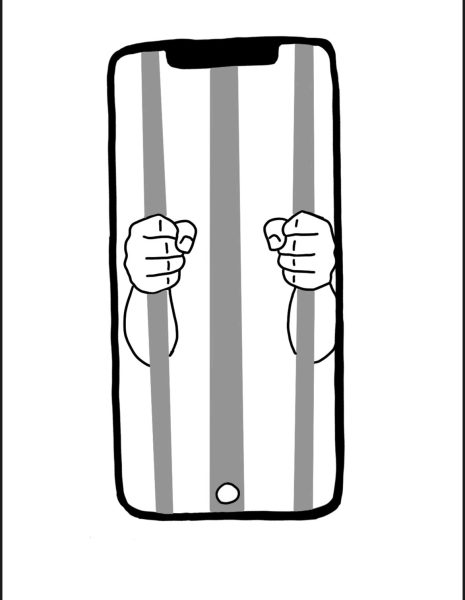

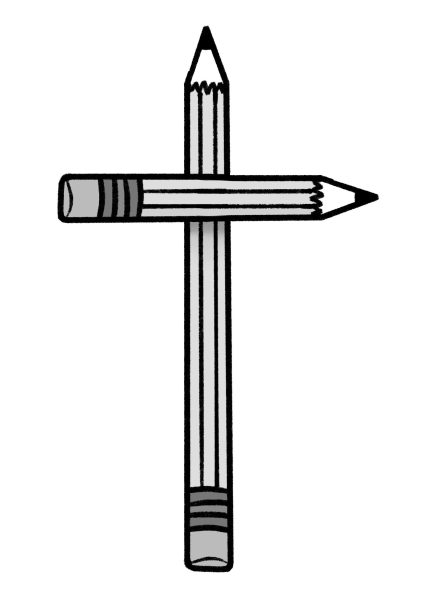

When focusing on the data, it might be hard to equate each statistic to an actual person. However, we must recognize that each percentage and number parallels the actual life of a Native person with their own personal experience and struggles facing oppression — my grandma being a part of that percentage. My grandma, Jane Trigg, was born into a small village in Nome, AK, home to the Western Alaska Inuits (Yupiks). At the age of five, she was taken away from her parents by social services and put into an orphanage in Seward, Alaska, with her 12 siblings. She grew up there until she was 19 years old, and also learned what it really meant to be a Native American in the U.S. Over her 15 years of living in the orphanage, she slowly lost her connection to her heritage and culture as she lived under a strict Christian lifestyle. In school, she recalled how the Inuit students were segregated from the white students and, as a result, being turned away from trying out for the cheerleading team, as only white children were allowed to. Even as an adult living there today, over 60 years has passed since she was a child growing up — she continues to face inequalities and sees that other Alaska Natives are struggling with them as well.

My grandma’s story shows her individual experiences with oppression and mistreatment towards Native Americans but are parallel with many individuals today, like the Chairman of the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe Brian Weeden. When talking about Thanksgiving from a Native American perspective in a Time article, he said: “it’s just another reminder of all the horrible things that this nation has done to not only us, but all Native people.”

On Thanksgiving, while others make feasts and fail to acknowledge the holiday’s dark origin, Native Americans are reminded of the genocide of their people and the land they lost. This is a prime example of why there needs to be more awareness and education about Native American culture and the mistreatment they endure. Although many Americans, including myself and my family, celebrate Thanksgiving, it should be celebrated with the awareness of its history: the irreparable shatter of Native Americans and their culture, and the broken pieces that are left to current and future generations.

Some may argue the Biden administration declaring the month of November as “Native American Heritage Month” is an honor and celebration of Native American culture. But this recognition fails to educate people on AAIN culture, history and present oppression. It also does not promote or create government action to stop the discrimination they face, or any tangible change at all. Continuing to make this issue known by educating on it, whether that be through school, Native American individuals or by educating yourself, will help promote the positive change that needs to be done.