It’s game over for lower-income athletes

October 30, 2021

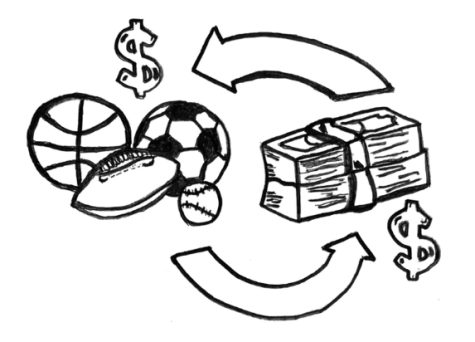

With more and more high school athletes trying to earn spots on college rosters, the prevalence of club teams traveling to tournaments in order to be seen by college coaches has greatly increased. This creates an economic gap that further segregates the rich and poor due to a pay-to-play aspect in club sports. If we want to ensure equality in the recruiting process, we must make scholarships for lower-income athletes more accessible, bringing forth more opportunities.

According to the Next College Student Athlete (NCSA), 90 percent of student-athletes who compete at the college level participated on a club team during the recruiting process. With club teams ranging in price from $700 to $35,000 a year, many parents cannot afford for their children to play. These families get less college exposure, which significantly decreases their chances of playing a sport at the collegiate level.

Tom Farrey, executive director of The Aspen Institute’s Sports & Society program, stated “When you have that kind of system, parents start spending a lot of money. That’s where you get them on the right club teams, hiring private trainers and doing whatever it takes — buying them the $300 special bat — to have them succeed at sports. It effectively pushes aside a lot of kids on the lower end of the income distribution.”

This issue is heavily prevalent in higher-income communities as they can afford to get the “best” equipment and have weekly private training sessions. For example, if someone has a $300 baseball bat, it is going to hit the ball much farther than a $50 bat. This creates unfair advantages to the lower-income families who can not afford it and as a result, will likely have to work harder to be at the same level. In some cases, kids won’t be able to play because of the expensive costs of equipment. The average cost of lacrosse gear is about $565 which doesn’t even include the traveling or club fees.

Project Play, an initiative of the non-profit organization Aspen Institute, creates change through leadership, dialogue and community action, to help bring awareness to the inequalities of youth sports. Their study found that, of families earning more than $100,000 a year, 69 percent of those children played a sport. However, in families earning less than $25,000 a year, just 34 percent participated in a sport. In comparison, Marin County’s household income was $115,246 in 2019, according to the United States Census Bureau. Furthermore, an October Bark survey found that 72 percent of Redwood students play a sport, and of that, 79 percent have been, or are currently, on a club sports team. With this being such a large percentile, it further proves the Aspen Institute’s findings as it will create advantages for athletes in Marin to play at the collegiate level. The Redwood class of 2021 had 24 athletes go on to play at the collegiate level and the class of 2022 and 2023 already have multiple commits.

With more opportunities for college camps and showcases available, club teams have increased prices over the years. According to USA Today, youth sports have become a $19 billion industry as of 2020, and are expected to grow to $77.6 billion by 2026. As the industry booms, the prices begin to rise. More upper and middle-class kids are playing and filling up spots on teams. Roster spots then become limited, which leads to price increases throughout the nation. This drives lower-income families farther away, as less and less will be able to afford it in the next few years.

Former goalkeeper for the United States women’s national soccer team from 2000-2016 Hope Solo revealed at the Hashtag Sports Conference that if she was a kid today, her family would not have been able to afford for her to play soccer. Solo believes that sports’ increasing prices is a prevalent issue, and the reason the U.S. has seen poor results in international soccer play. The U.S. men’s soccer team has never won a medal and has continuously failed to qualify for the Olympics since 2008. The favored U.S. women’s team also failed to bring home the gold in 2021. Solo believes this is due to the U.S’s dividing racial and economic classes.

“We have alienated the Hispanic communities. We have alienated our Black communities. We have alienated the underrepresented communities, even rural communities, so soccer in America right now is a rich white kid sport,” Solo said. “No wonder we are not qualifying for the World Cup when we have alienated a huge population of really talented youth soccer players. And that’s the state of the game right now.”

I am on a club softball team located out of Concord, Calif., and I see these inequalities firsthand. One of my former teammates’ parents could barely afford to take her to our tournament in Colorado. They both had to pick up double shifts and work on the weekends, so she could attend the tournament. The family drove to the majority of the out-of-state tournaments throughout the season to save money. She told me she would feel awful if she didn’t play softball in college because of all the money and time it has cost, and that it would almost be a waste. While many younger athletes strive to play at the college level, only seven percent receive the opportunity, according to the NCAA. Many lower and middle-class parents have to sacrifice time and dedication, so their kids can have the chance to play at the next level. But what about the kids who still can not afford it?

Scholarship programs need to be offered alongside these club sports teams, ultimately giving everyone a fair opportunity to play. None of the club teams I have been a part of have publicly offered scholarships to players, which counteracts the goal of the team: to build the best lineup possible. For club sports, the organization cares only about the money they produce and will do whatever is needed to maximize profits.

Although many Marin County club teams do not offer scholarships, North Bay Basketball Academy (NBBA) is an exception. They partnered with Kimo Bear Project, a non-profit organization that provides kids with cancer with a Kimo bear during treatment. Through the partnership, Kimo Bear is now helping NBBA athletes in need of financial aid and is providing scholarships. More club teams need to follow NBBA’s efforts to address the pay-to-play mentality. Student-athletes, whose families can afford club team fees, travel expenses and private lessons — which can range from thousands of dollars — have a noticeable advantage. Closing this significant equity gap is possible with supporting partnerships.

Programs such as the Junior Giants have donated over $34.5 million to provide kids the opportunity to play baseball, and the funds have built fields in the Bay Area as well as other parts of California, Nevada and Oregon. Other programs such as Every Kid Sports and All Kids Play provide scholarships and opportunities for young athletes, allowing them to participate in sports. Club teams should be teaming up with bigger companies, like NBBA teaming up with Kimo Bear, so low-income kids can have equal opportunities to continue their sports careers into college.

“It’s not enough to change the dynamics of soccer in America unless somebody from the top helps. This means U.S. soccer and the $100 million in surplus funds needs to be distributed throughout amateur soccer,” Solo said.

By club teams not stepping up, they are putting low-income athletes at a disadvantage, a disadvantage that will damage the entire sports industry.