Phasing out hazing: It’s time for a new kind of initiation

June 8, 2021

In October 2019, 18-year-old Cornell University freshman Antonio Tsialas was found dead in a ravine near the campus. The night before, he attended a Phi Kappa Psi fraternity party where freshman recruits were encouraged and/or forced to binge drink alcohol in the name of loyalty. Fraternity brothers even dunked the heads of intoxicated recruits in water as a test of tolerance. The investigation into Tsialas’s tragic death was inconclusive, but Cornell officials ultimately determined hazing was involved. They revoked recognition of Phi Kappa Psi.

In February 2021, Virginia Commonwealth University freshman Adam Oakes drank extensively as part of a Delta Chi initiation party. He later passed out on a couch, and when fraternity brothers awoke the following day, they found Oakes unresponsive and his face purple. After calling 911, Oakes was pronounced dead at the scene.

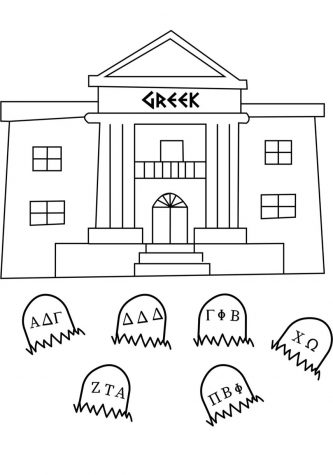

Initiation is a signature tradition in Greek organizations. Fraternity and sorority members recruit underclassmen to become a part of the brotherhood or sisterhood through participation in challenges and team bonding exercises. These rituals allow recruits to connect with housemates and prove their fidelity to their new community.

Despite the appeal to bond with like-minded peers, initiation practices have taken on an increasingly deadly turn. Hazing, a more violent and aggressive form of initiation, degrades pledges and often results in severe emotional and physical consequences. A centuries-old practice, hazing is defined by the Oxford Dictionary as “humiliating and sometimes dangerous initiation rituals.” The term was first used in 1684 when a Harvard University student was expelled for hitting underclassmen as part of an upperclassmen custom of asserting their dominance.

Despite the appeal to bond with like-minded peers, initiation practices have taken on an increasingly deadly turn. Hazing, a more violent and aggressive form of initiation, degrades pledges and often results in severe emotional and physical consequences. A centuries-old practice, hazing is defined by the Oxford Dictionary as “humiliating and sometimes dangerous initiation rituals.” The term was first used in 1684 when a Harvard University student was expelled for hitting underclassmen as part of an upperclassmen custom of asserting their dominance.

Since then, it seems that fraternities and sororities have been competing to create the most outrageous hazing practices, devising increasingly dangerous rituals, which often include excessive alcohol consumption, intense physical activity to the point of injury and humiliation or emotional abuse. From “boob ranking” of sorority pledges lined up shirtless according to breast size, to fraternity pledges carrying feces through a forest and drinking urine along the way, there seems to be no end to the humiliation and torture.

More than half of American college students experience some form of hazing, and 95 percent of hazing incidents are not reported to administrators or other school officials. There has been at least one hazing death in the United States every year between 1958 and 2019, with a break in 2020 due to pandemic-driven shutdowns. 82 percent of all hazing deaths involved alcohol. These numbers are staggering and beg for reform, but university officials and lawmakers have failed to effectively regulate the problem, as demonstrated by Cornell’s meager response to the death of Antonio Tsialas. As of 2019, hazing is illegal in 44 states, yet 73 percent of Greek fraternities and sororities across the country still engage in these traditions. Considering that 63 percent of members on the US President’s Cabinet are former members of Greek organizations themselves, their reluctance to step in is unsurprising.

Some schools, however, have proven that effective legal actions can be taken to combat hazing. One example of a meaningful legal response came in Florida in 2014. Former Florida A&M University student Dante Martin was sentenced to six years in prison for manslaughter and felony hazing in relation to the death of Robert Champion, who was brutally beaten during a hazing ritual in 2011. Yet, without consistent consequences for hazing deaths like this one, frat boys will continue to be frat boys.

Given the prevalence of hazing tragedies, university administrators also need to create and execute stricter policies on campus. Likewise, student leaders need to take responsibility for forging change by evaluating dangerous traditions, regulating initiation rituals and raising awareness about the consequences of hazing. Additionally, high school seniors should be educated about the dangers they might face when they arrive on college campuses. When your head is being held under water after being forced to drink a half bottle of vodka, it may be a little too late to strategize. Let’s be real; peer-pressure training from middle school likely won’t cut it, either.

There is some good news, though. Not all Greek organizations rely on hazing practices to initiate their members. Sigma Phi Epsilon sorority, a national Greek organization, is an example of positive initiation practices welcoming members without hazing. Pledges are judged based on meaningful behaviors including proper etiquette, yoga/meditation practices and even cooking skills. In contrast to hazing, initiation processes within Sigma Phi Epsilon typically build camaraderie, trust and relationships among students seeking to become part of the community. By all accounts, it seems to be working. Campuses need more Sigma Phi Epsilons.

According to a May Bark Survey, 34 percent of students plan to rush a Greek organization in college. These students would benefit from preparation regarding the dangers and extent of hazing practices. They will need to stand up for themselves and access strategies to manage if and when they encounter hazing practices as freshmen. Redwood should be a part of this education. The future wellbeing of Giants is at stake.