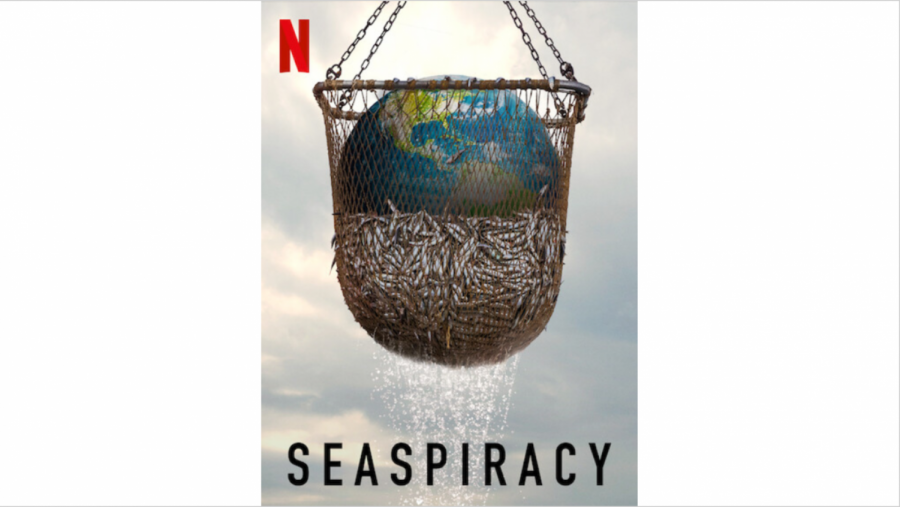

“Seaspiracy,” a documentary recently released on Netflix, uncovers the harsh realities of plastic pollution and animal hunting, specifically in our oceans. Especially during a global pandemic, it is easy for people to forget about other global crises that need urgent attention. Thus, it is notable that the film hooks viewers from the beginning by applying the issue to the audience, making the catastrophe feel far more personal.

“In a world concerned with carbon [emissions] and climate change, protecting these animals [means] protecting the entire planet…if the ocean dies, so do we,” Ali Tabrizi, the film’s journalist, director and narrator, said.

The film was riveting from the start, leaving the audience on the edge of their seats and wanting to know more. This technique was efficient in making sure viewers were captivated, as the documentary evolved into somewhat of an exposé.

As far as the portrayal of the information goes, the use of music during the film set the tone for the dismal discoveries and investigations that were going to take place throughout the making of the film. When the tempo of the music would quicken, the sense of anticipation and nerve surrounding that given section of the story would enhance as well. Conversely, there were also points in which there was no music and the attention was fully placed on the voices of people, further emphasizing the conversation at hand.

Tabrizi was persistent throughout the film, trying to interview a variety of individuals from different companies that had administered sea animal hunts, or claimed to be the frontline of eco-friendly movements. The camera crew provided a variety of angles, picturing both Tabrizi, the interviewee, the setting, and other important items present to establish the crucial background and setting for the audience. However, most interview attempts failed, as the interviewees refused further questioning and demanded cameras be shut off — a clear sign that something was being hidden from the public. Nevertheless, Tabrizi went on to investigate the lies and fabrications that these companies and organizations were publicizing for personal gain.

Along with this, he found that plastic straws only account for 0.03 percent of plastic entering the ocean, and the best-proven way to sustain the ocean was to consume less fish, thus limiting fishing industries and their pollutive netting gear. This information was enlightening, as the world was quick to adapt to using alternative types of straws, with some restaurants excluding pasting straws entirely, despite this being a microscopic aspect of ocean pollution. The connections the film made between the direct problem at hand (“sustainable” seafood) and everyday items once again put the issue into perspective, and effectively laid out the dimensions of the problem.

Although it seems obvious that eco-friendly organizations would promote anything to help the oceans, when Tabrizi asked the Plastic Pollution Coalition why they would not advertise the idea of lessening fish consumption, they refused to answer, and insisted that cameras be turned off. They claimed they had no opinion on the topic.

Even the Marine Stewardship Council, the world’s largest sustainable seafood organization, refused to speak to Tabrizi about sustainable seafood. The filmmakers did an excellent job of pushing the limits just enough to get a point across to the audience that something fishy was going on behind the scenes. However, there were points in which the creators were deliberately breaking the rules and wishes of those they were interviewing or reporting on. No matter the perceived importance of the investigations Tabrizi was conducting, his continuation to record those who requested not to be on camera, and use of film to directly capture signs mandating that photography or videography was not allowed, seemed to disregard the rules of journalism.

Nevertheless, without the publication of documentaries like “Seaspiracy”, it is likely that many would remain oblivious to the ulterior motives of these supposedly helpful institutions, as they withhold the truth behind ocean pollution to make maximum profit. Tabrizi’s decision as a journalist to publicly pursue such a controversial issue, and share his controversial findings, are reason enough for individuals to watch the film.

Moreover, the use of animal noises, accompanied with visual footage of the creatures at risk, assisted in connecting viewers to the forms of life proven to be at risk. Ultimately, the use of graphics at the end was gruesome to a point that I can only imagine viewers were left scarred and moved, proving a proficient use of imagery on the documentary’s behalf. Seeing the brutalities of these problems up close was a final wake-up call to those unaware of the misguided intentions of such a substantial majority of supposedly eco-friendly organizations.