Failing grades spike during R1 of remote learning

December 16, 2020

“I definitely have way more homework than last year because teachers often give Zoom lectures or extra readings because they don’t have time to lecture in class. … I just feel like I’m learning a lot less,” junior Lauren Duncan said.

Duncan is now managing four Advanced Placement (AP) and two regular courses online. Despite her heavy workload this school year, her classes are not providing the same level of education as they would in-person. This combination appears to be a common theme throughout the virtual student body and is one of the factors that contributed to a decrease in academic performance during the R1 grading period.

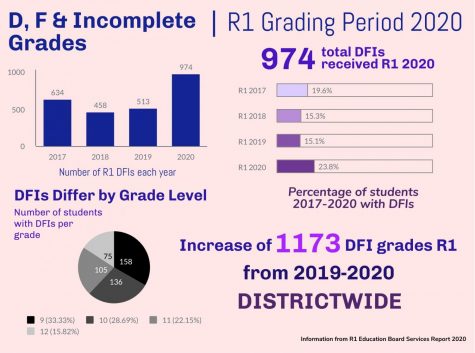

According to a November Bark survey, 51 percent of students feel they are performing about the same as last year, while 30 percent feel they are doing worse and 19 percent have improved. Despite this, the total number of D, F and incomplete final grades (DFIs) students received for the R1 period amounted to 974, marking an increase of 440 from the average of 534 at R1 over the last three years.

Math teacher Allison Kristal attributes this uptick in DFIs to the lack of proper supervision and communication on Zoom, a defining characteristic of a traditional classroom setting. In her opinion, online learning has divided kids into two distinct groups: those who are doing well, and those who are seriously struggling under an online system.

“I still think there are plenty of kids doing well,” Kristal said. “The difference is that a kid who [was] not doing well is [now] doing really poorly. I feel like the middle ground [between student grades] is not really there. And it’s hard to know how to fix that.”

According to administration data, R1 DFI figures were distributed evenly among subject departments. However, they differed greatly among grade levels; the majority of students with failing or incomplete grades were underclassmen. Out of the 474 students who received DFIs in R1, 158 were freshmen and 136 were sophomores. This is a major difference compared to the 105 juniors and 75 seniors who received DFIs during this same period.

Kristal attributes this disparity to the absence of the traditional acclimation to high school that underclassmen would normally undergo.

“I think that has to be one of the hardest transitions because they finished their eighth-grade year remote, and then they’re at a high school where you don’t know the school community or the expectations,” Kristal said. “[As a result], I feel like our freshmen aren’t accessing the resources that the students that have been here for a few years are aware of.”

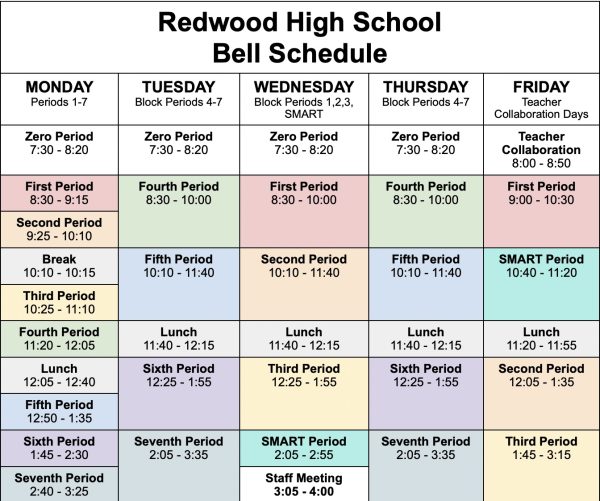

One of these resources is the now-virtual SMART guidance periods, which, in Kristal’s experience, are attended overwhelmingly by upperclassmen, while freshmen rarely stay to ask for help. Also, since many middle schools that feed into Redwood adopted universal grading systems last spring, their DFI count reflects how the abrupt switch to strict letter grades and higher curriculum expectations could be even more difficult for incoming freshmen.

These statistics have motivated Vice Principal Saum Zargar to develop a socially-distanced orientation before the spring semester in the hope of improving overall class performance and engagement.

Another disproportionately affected population is the students of color at Redwood. Although they comprise only 27 percent of the student population, this demographic represents 41 percent of students with DFI marks. Zargar attributes this to the inherent disadvantages of many minority groups in Marin County and across the nation that often affect their technology and schoolwork resources.

“Not all students have the same level of access at home or in the community, and we need to do what we can to not only support them academically, but socially and emotionally,” Zargar said.

Redwood’s administration and staff are attempting to extend this principle to all students, especially due to the increased anxiety and isolation during the quarantine that can exacerbate pre-existing academic difficulties.

In response to the DFI increase at the end of R1, teachers and counselors began reaching out to visibly struggling students. Redwood’s administration and staff also set up several new provisions, including learning hubs on campus, Zoom tutoring and wellness resources. As a result, Kristal has seen a major improvement in academic performance and believes students’ grades in her classes are now similar to previous years.

“We saw more [DFIs] at R1 than R2 because a lot of kids kicked it into gear and figured out what they were supposed to be doing by the time we got to this most recent grading period,” Kristal said. “I noticed that my DFIs were about normal at the R2.”

Although Marin appears to be edging towards the purple tier that would prevent a return to in-person school in January, Zargar’s motives align with the 88 percent of families throughout the district who voted in October to return to the classroom in a hybrid model.

“We are very much motivated and dedicated to bringing students and teachers back on campus safely in January,” Zargar said. “We know we can do our best work when students are with us on campus.”