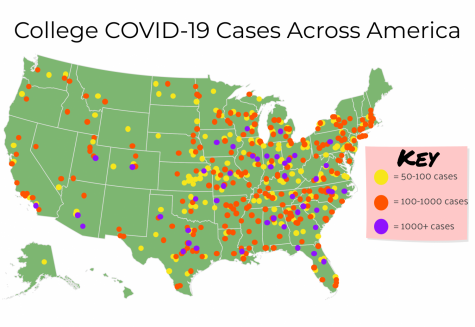

As the fall semester began and the COVID-19 pandemic continued to be relatively controlled, administrators across the U.S. had to wrestle with a difficult question: how to reopen. About half of American universities and colleges chose to go primarily or fully online for the first semester, according to the Chronicle of Higher Education. However, several schools have opened their campuses to students while still attempting to control COVID-19, and the outcomes of in-person learning have varied substantially.

The University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill, with an undergraduate population of approximately 20,000, opened in mid-August with about 5,800 students in dorms and others living off-campus. More than half of UNC’s undergraduate classes included face-to-face teaching, with social distancing and mask wearing. After merely 10 days of in-person classes, upon expert recommendation, UNC abruptly closed. According to the UNC-Chapel Hill COVID-19 Dashboard, in the week prior to the shutdown, the positivity rate was 13.6 percent among a testing pool of 954 students.

Taylor Charles, a UNC freshman and Redwood alumnus, lived in an off-campus dorm until UNC’sfull closure. He believes that although the university took the necessary precautions on-campus, the virus ultimately spread through the socialization on weekends and off-campus, where students were not following COVID-19 health guidelines.

“The masks and the social distancing [protocols] were actually done super well [on campus]. All on-campus activities either weren’t happening, or they were happening virtually. Everything UNC had control over was solid,” Charles said. “But it was the weekend life where it spread. [The social life] didn’t feel that different and I think that was the problem. Everyone was still going to have fun, no matter what.”

According to Charles, UNC-Chapel Hill only tested self-reported symptomatic students and did not require testing for students before they initially came onto campus in the fall. Although the school was trying to test all symptomatic students, it was not uncommon for those who felt sick not to report themselves.

“When you’re a freshman in college, it’s exciting. You want to go out and socialize, [you] don’t want to get put in isolation dorms the first week on campus. So a lot of kids who did have symptoms wouldn’t get tested… they just lived by [the thought], ‘If I don’t get tested, I don’t have [COVID-19],’” Charles said.

Conversely, Cornell University, which has about 15,000 undergraduate students, has a very different approach to the testing process that has allowed it to remain open this school year. During the final two weeks of September, they had only six positive student cases, with a positivity rate of 0.01 percent.

Unlike UNC-Chapel Hill, Cornell screened students prior to arrival on campus and has ongoing, frequent screening of students who live on campus or in the Ithaca area, as well as faculty and staff, regardless of symptom presence. Participation is required by a student compact, which every student had to sign before coming to Ithaca, even if they are living off campus.

Julia Scharf, a sophomore at Cornell and Redwood alumna who is living in off-campus sorority housing, believes that students are trying to keep one another safe and prevent the virus’ spread by complying with Cornell’s guidelines.

“There’s a certain level of responsibility that everybody here feels so that we can all stay on campus. So it’s not cool to break the rules… and not cool to endanger other students and people here aren’t trying to [do so],” Scharf said.

Sam Abbott, a University of Notre Dame freshman and former Redwood student, feels Notre Dame’s student body has a similar perception and approach to mitigating the virus.

“[Students here] have a commitment to the greater good. That’s something put on Notre Dame students and something that kids take very seriously,” Abbott said. “They’re doing things, not just for themselves, but for the greater community, even if that means sacrificing certain social [activities] so that everyone can stay on campus.”

Unlike Cornell though, Notre Dame originally struggled with the virus. According to its COVID-19 Dashboard, the university had 304 new student cases and a positivity rate of about 18 percent from Aug. 17 through Aug. 20. Because the rates were rising so rapidly, Notre Dame took action and transitioned to an online school format, but they kept the student body on campus under quarantine. During this time, Abbott and other students were extremely fearful of school closure.

“Thankfully, after talking with the health officials, [Notre Dame] decided if we’re able to put a pause on activities for two weeks, that should stop the spread. If we’re able to restart from there with more testing and better adherence to COVID guidelines, we might be able to make this work,” Abbott said.

After two weeks of shut down activities and in-person classes, Notre Dame was able to reopen with in-person classes. Since then, in the month of September, Notre Dame had a positivity rate of 1.2 percent, according to its COVID-19 Dashboard. Abbott attributes this success largely to a change in the testing process.

“I think the most important thing is that originally the university was only testing symptomatic people and then contact tracing them, but now, we have a bunch of surveillance testing [trying to] catch all the asymptomatic spread,” Abbott said.

By contrast, the University of Colorado Boulder, which currently has an undergraduate population of about 30,000 students, is struggling to contain the virus. After having a spike of about 418 new student cases and a positivity rate of around 29 percent between Sept. 16 and Sept. 21, the university went online and put students in quarantine to slow the spread. From Sept. 24 to Oct. 8, when the school was fully virtual, students were not supposed to leave their on-campus housing with anyone else unless there was a safety concern, in which students were allowed to be outside with one other person.

Christopher Fuegner, a Redwood alumnus and freshman at Boulder, believes the university and local police were being particularly strict.

“[Boulder] and the cops are very on it. They’re all over the place ticketing people like crazy for being out in groups. So, people are definitely following the rules and it’s keeping us inside and it definitely slows the spread a lot,” Fuegner said.

According to Fuegner, the administration was relaxed about the rules at first, but now, the school has become stricter and students adhere to regulations more often. Since this change and the transition online, Boulder’s numbers have decreased substantially — an average of about 4 new cases arise each day in the first week of October compared to an average of 79 in the week before they went online.

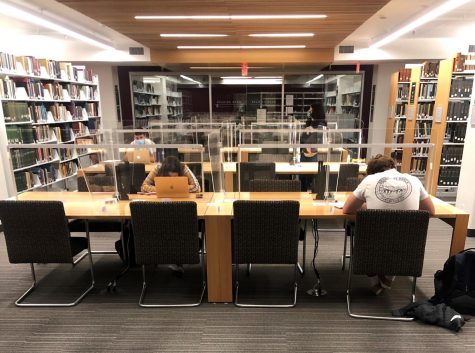

Unlike Boulder, Swarthmore College has controlled COVID-19 since its students arrived on campus in August. Currently, Swarthmore, with approximately 1,500 undergraduate students, has a closed campus occupied by only freshmen and sophomores, which equates to about 600 students. Since the beginning of the semester, the school has had only one student case.

Ed Rowe, the chief of staff and secretary of the college at Swarthmore, believes that testing was a large component in keeping low rates when students arrived.

“We determined that we wanted regular testing. When students arrived on campus, before they got the key to go to their residence hall room, they had a COVID test. They were [also] tested again one week and two weeks after moving in. We only had one positive case, so I think students were really taking precautions seriously before they got to Swarthmore,” Rowe stated.

Due to its low COVID-19 rate, Swarthmore admin decided it could relax the amount of testing, now just testing a fourth of the student population each week and the full staff weekly. As a whole, Swarthmore has the capability to accommodate 900 students safely, but instead kept the population small as an extra precaution. Rowe is grateful that Swarthmore is able to proceed safely and not be concerned about monetary problems.

“Swarthmore is fortunate to have a large endowment and significant financial resources, so we could afford to take a very conservative approach. If we didn’t think it was safe to bring any students back, we wouldn’t have brought any,” Rowe said. “This is an existential crisis for a lot of colleges and universities, and I’m glad that we aren’t forced to weigh those kinds of trade-offs. We can really just determine what is an acceptable level of risk and let that be the driver of our decisions.”

As the world attempts to control COVID-19, colleges give an uplifting blueprint for how to contain the virus. With numerous factors impacting schools’ decisions to stay open, the key to success seems to be rigorous testing of everyone, symptomatic or not, as well as adherence to the rules. Through tight control and compliance, many colleges are able to remain open and continue with in-person classes.