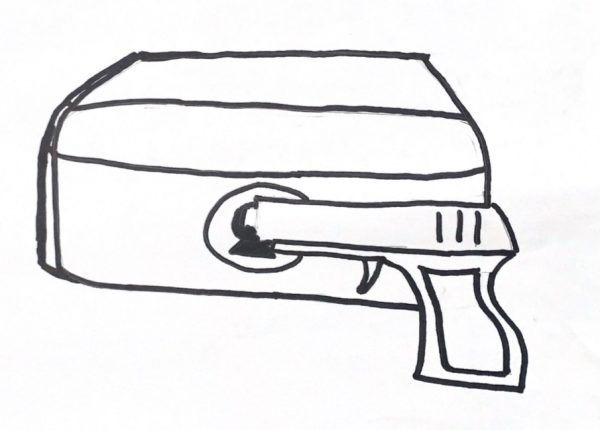

Lingering quota-based policies in police departments discourage duty to serve and protect

March 16, 2020

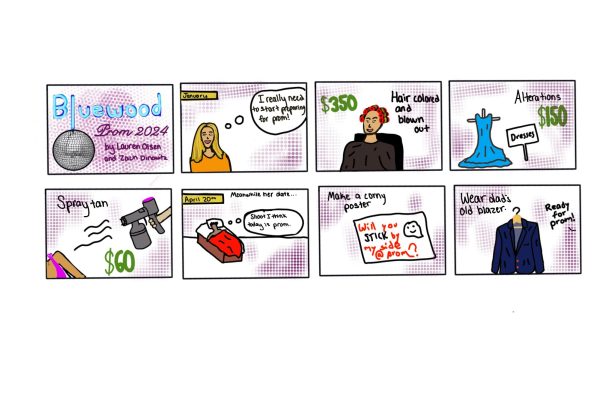

“I was pulled over last year for speeding when I was only four miles over [the limit]. The fine ended up being $500. The officer that pulled me over told me I should really be more careful the last days of the month because [police officers] typically patrol high traffic areas so they can meet their monthly ticket goals,” Greer Hooker, a senior at Fayetteville High School in Arkansas, said.

“I was pulled over last year for speeding when I was only four miles over [the limit]. The fine ended up being $500. The officer that pulled me over told me I should really be more careful the last days of the month because [police officers] typically patrol high traffic areas so they can meet their monthly ticket goals,” Greer Hooker, a senior at Fayetteville High School in Arkansas, said.

Anyone who has ever received a traffic ticket understands the frustration of having to put your hard-earned money straight into the police department’s pocket. Especially in Marin, where the violent crime rate is 1.8 per 1,000 persons according to the Marin Sheriff’s Department, it seems like police officers do nothing but sit and wait to issue tickets.

Fines attached to traffic tickets are supposed to be punitive, a minor punishment for driving dangerously and a motivation to refrain from disobeying traffic laws in the future. However, fines have gotten significantly more expensive in the last decade. According to Elisa Della-Piana, legal director of non-profit Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights of the San Francisco Bay Area, for years the state legislature has created multiple add-on fees to raise revenues without having to deal with the community disapproval of tax raises. With these additional fees, a $100 stop light ticket turns into a steep $490 fine, according to LCCR’s report, Paying More for Being Poor: Bias and Disparity in California’s Traffic Court System. In some states like California, fines for speeding violations are now as much as eight times more expensive than they were in 1993, according to Los Angeles’ KCAL-TV.

With more generated revenue from steeply-priced tickets, cities have actually begun to depend on that ticket revenue to fund their departmental operations. This means that a certain amount of tickets must be issued to balance budgets. However, to protect the legitimacy of the system’s goals, police officers need to focus on the quality of their work, not quantity. Police officers are not here to serve as revenue generators and should not be controlled by unethical departmental practices.

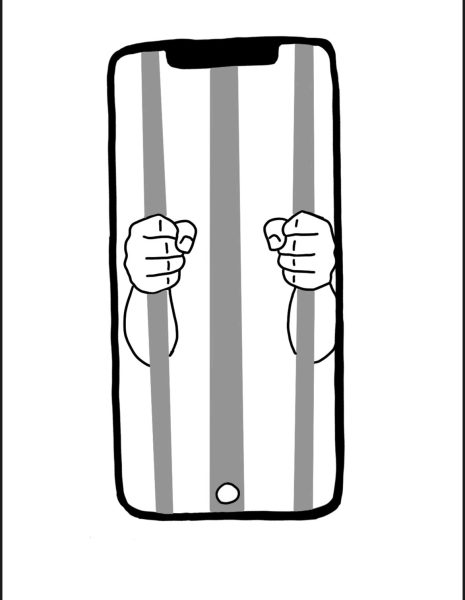

In an attempt to limit the overissue of tickets, state governments have taken action to ban quotas. In California, officers are explicitly banned from adhering to ticket quotas, under California law (Cal. Veh. Code § 41602 (West 2011)). However, despite laws and lawsuits, quota-based law enforcement policies linger, unintentionally putting more importance on revenue rather than security and service.

Whittier, California, like many other cities around the country, has found methods to get around the state law banning explicit ticket quotas. Using a technique called “shift averaging,” supervisors tally up the number of tickets handed out by teams of officers on various shifts and punish anyone who fails to meet or exceed the mean number of tickets per shift. In other words, there is no actual quota; however, the loophole designed by certain police enforcement agencies lends itself to unjust behavior as officers strive to issue the most tickets that month.

When an officer is required to enforce a minimum number of arrests or to issue a specific amount of citations, public safety becomes secondary as the need to meet ticket goals is prioritized. With these policies, the officer’s mindset naturally focuses on the number of people they need to catch rather than the action needed to take to keep the community safe. Not only are perceptions of police officers as collection agents undermining department trust, but they are also damaging the legitimacy of operations.

Instead of feeling forced to write a certain number of tickets, an officer should be able to apply his or her judgment to make a rational decision about whether a citation or warning is necessary. Officers are trained to administer the law and help serve justice, but they should also be able to make mercy calls when needed.

Of course, being mostly dependent on ticket revenue makes it difficult to completely eliminate this type of fund. By placing limits on how much of an agency’s budget could come from such mechanisms would ensure departments are transparent with their finances so the community doesn’t feel taken advantage of.