Appropriation of feminism is the new feminism, and it’s perpetuating a negative connotation with the movement

Expressing feminism can be shown through accessories or other items. Some student feminists wear pins on their backpacks or place stickers on water bottles.

February 16, 2019

A modern rendition of feminism has birthed a new meaning, leading it to become a controversial term. The negative connotations associated with feminism are common among our generation, leading some to believe that the word “feminist” is misrepresented by the media, literature and politics. The true meaning of “feminism”—the advocacy of women’s rights on the basis of the equality of the sexes—has been lost over the years of misrepresentation, mainly on behalf of the media.

The media’s portrayal of feminism is polarizing to many, including junior Branden Newhard. Though he is a believer in gender equality, Newhard is still hesitant in calling himself a feminist.

“I am pro-women’s rights, and I support their movement, but sometimes I don’t support the way that they go about trying to explain themselves and hyper-victimize themselves,” Newhard said. “Some people do it in a respectable manner, but some people just don’t do that, and I think that’s what the media portrays. You see it on Instagram all the time, you see videos of [women] freaking out over small stuff. That’s why feminism has a bad reputation.”

Newhard’s perspective is common among teenage boys, as they are exposed to women being radical feminists through social media and the internet. Similar to Newhard, junior Kaden Gibbs believes in gender equality but does not call himself a feminist. According to Gibbs, his version of feminism is a world where everyone is equal.

“I think most people, when they think of feminism, think of the extremely intense feminists––the ones that hate men and want more than just equal rights. But in truth, that’s a really small part of the population and I think most women are actually trying to fight for equality,” Gibbs said.

In a recent poll by Refinery 29 and CBS News, 46 percent of the women surveyed considered themselves to be feminists, while 54 percent did not. The majority of these women believed in gender equality but didn’t identify as feminists due to radical feminism, a perspective within feminism that calls for a radical reordering of society in which male supremacy is eliminated in all social and economic contexts.

When Redwood English teacher Danielle Kestenbaum was in high school, she saw the stereotypes associated with radical feminism. Kestenbaum thinks the negativity stemmed from stereotypes of the 1960’s like ‘burn your bras’ or ‘don’t shave your legs,’ but for her, it’s just about fighting to have women at an equal place in the world.

“On the first day of our high school sociology class, for the gender unit, our teacher asked us, ‘What’s a feminist?’ Everyone started bringing up all the stereotypes,” Kestenbaum said. “What feminism [is] at the root is a belief in equal rights for men and women. I think there’s a huge misunderstanding about that. That was something that was really eye-opening. Feminism is such a simple idea that our country has complicated so much.”

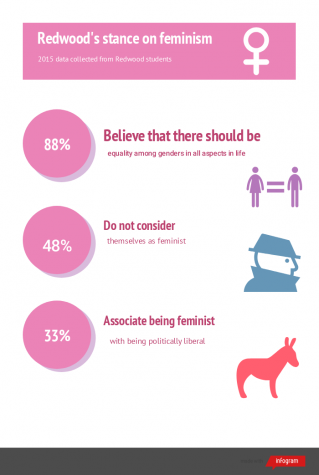

In a 2015 self-reported Bark survey, 88 percent of students believed in gender equality in all aspects of life, yet 48 percent still did not consider themselves feminist. The word “feminism” has been lost in translation. “Feminist,” though, has many different interpretations.

According to Newhard, his view on feminism has been skewed due to the overexposure of radicalism in media.

“I think that radical feminism is something different than what real true feminists are. What’s portrayed on media is something that’s completely different and it’s changed my belief on feminism,” Newhard said. “I believe in equal rights for everybody and that everyone should be given the same opportunities, but I don’t think it’s fair to wish death on someone who isn’t always showing equality.”

However, others such as junior Ashley Acosta do not believe that social media is skewing the true meaning of feminism.

“I think the media has portrayed feminism in a good way, especially because a lot of media people show up at the Women’s March. I don’t think there’s much negativity around it,” Acosta said. “I don’t think people make jokes about it anymore. I don’t see feminism come up very often besides when the Women’s March comes around, but I don’t think there’s much negative connotation around it.”

Acosta believes that politics have stunted the growth of gender equality, rather than the media. Acosta believes that President Donald Trump has turned more people against feminism and that women are viewed again as objects.

“All these ideas that were created in the past are coming back again, especially with ‘Make America Great Again.’ [Trump] just wants to make America how it was, and if you think about it, a lot of things in America’s society weren’t good. Degrading women isn’t a good thing and now he’s bringing it back and seeing us as objects,” Acosta said. “He’s making it seem okay to think like that when it’s really not. He’s making it more acceptable among boys to be sexist, which is probably why a lot of teen boys think it’s okay to be anti-feminist.”

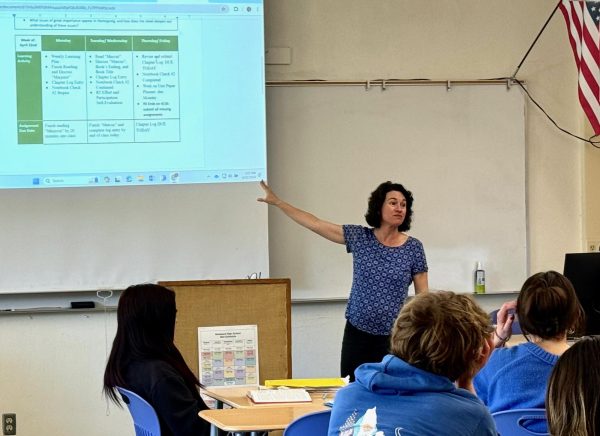

People like Kestenbaum are pushing back on the negativity surrounding feminism. As a sophomore English teacher, Kestenbaum embeds concepts relating to feminism in her lessons throughout the year. According to Kestenbaum, it is more than just a unit. In the 2017-18 school year, it was the throughline of her entire sophomore curriculum, and this year she is further incorporating it into the Humanities program.

“Last year, I set out to design a curriculum for sophomores that was all female authors and poets, which, going through the sophomore-approved curriculum, there were not enough female writers that are on the approved curriculum to fill an entire year,” Kestenbaum said. “It was really shocking. It made me realize that it was really important to have stories of women being told and being shared.”

As a teacher, Kestenbaum has the power to take action and make a change within her classroom community, and allow her students to spread that change beyond her classroom walls.

“A lot of associations come into sexuality as a feminist, a lack of education, a lack of understanding, and I think it’s great that we’re talking about these issues a lot earlier and a lot younger,” Kestenbaum said.