“This land is your land, this land is my land/From California to New York Island/From Redwood forest to Gulf Stream waters/This land was made for you and me.” Admit it, you sang that in your head. It’s fine if you did after all, “This Land is Your Land” by Woody Guthrie is part of almost every elementary school’s repertoire of songs. However, what this all-American song doesn’t say is that the land for “you and me” was paved on the backs of countless Native Americans.

The United States of America began making treaties with Native American tribes around 1778. The treaties negotiated border expansion and behavior between tribes and settlers, often taking advantage of the Native tribes. According to Partnership with Native Americans, the U.S. government has made over 500 treaties with Native American tribes, and yet, over 500 treaties with Native Americans have been broken, changed or nullified by the U.S. government since the beginning of negotiations.

The mistreatment of Native Americans is not a struggle of the past. In 2016 the Dakota Access Pipeline gained the approval it needed to build a pipeline to transport oil, despite construction plans showing it pass through sacred land in the Standing Rock Sioux, a native tribe. Over 200 members of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe went to protest the threat that the pipeline posed to the environment, human health and human rights. By these members being ignored, the government took a clear stance on how it values Native Americans. Ian Williams, a man who closely documented the impact of oil production on Native American people, said in an interview with Time magazine, “The oil industry consumes the ecology. It poisons the water, it eats up the land, it displaces the natural migrations of caribou and moose and other animals that the nearby Native American communities rely on.” Despite knowing this, the pipeline was approved in February of 2017 under the Trump administration, and was completed by April of 2017. Just months later, in November of 2017, the pipeline leaked a total of 210,000 gallons of oil. The fact is, the pipeline is not only a gross display of the disregardment of past treaties, but also, a show of apathy of the basic needs of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe members. By the U.S. government allowing the Dakota Access Pipeline to be constructed, it shows exactly where their priorities lie: not with the cultural preservation of the nation’s first people, or with their own integrity, but rather with big companies looking to make a profit.

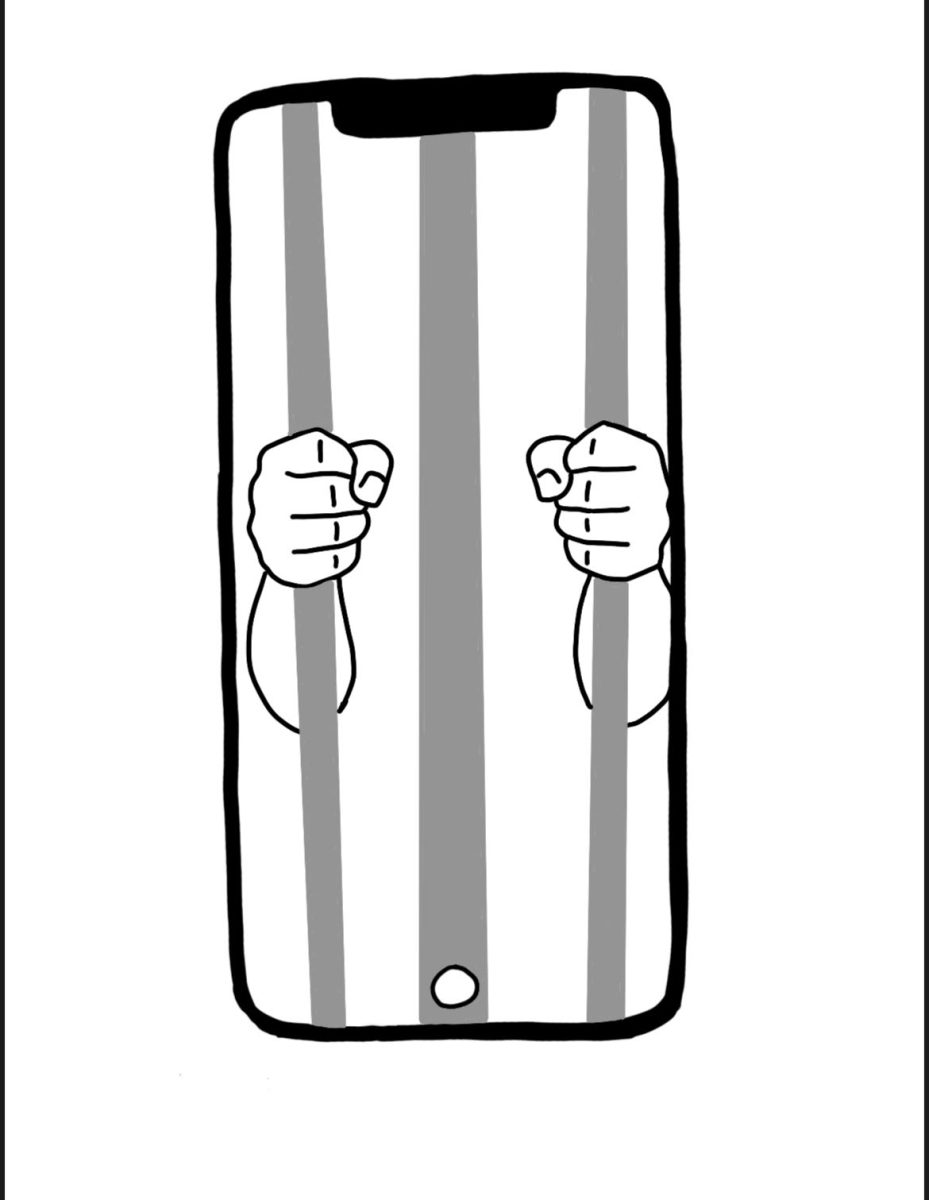

Past and recent oppression such as this can lead to some devastating outcomes. Poverty rates on Native American reservations are extremely high, for example, on the Standing Rock reservation, the poverty rate is 43.2 percent, according to the Pew Research Center. This compares to the national average poverty rate at 12.7 percent. The high rates are largely due to low education and employment levels, substandard housing and an already poor economic infrastructure. Native Americans on the reservation aren’t getting the support that they need, especially when Native American women are only making 59 percent of what a White man makes. Those living on reservations are stuck in poverty mainly due to the government placing reservations far from fertile land, population centers, water supplies and other resources. They are left in geographic isolation. The Native people have been disadvantaged in history, and, due to things like this, will continue to be in the future.

The Native people are not just tied to reservations. They live in large cities and rural countrysides as well, and despite the differences in terrain, one thing connects them: their native background. After leaving a reservation, their connection to their native heritage is usually disregarded by American’s of other races. One native man, Julian Brave NoiseCat shared his experience in an interview with Time Magazine.

“Being Native in a city is almost a daily reminder of your people’s erasure, of the fact that people don’t even remember that you’re here and that you exist,” NoiseCat said.

Admittedly, the history of mistreatment against Native Americans does get some recognition. Many exhibits displaying the injustices of the past have opened up in Washington, D.C. The Smithsonian’s Museum of the American Indian opened a rare exhibit displaying broken treaties of the past. It’s main feature is the Treaty of Canandaigua, a treaty between the U.S. government and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, otherwise known as the Six Nations. It displays the promises the U.S. government has failed to keep, and the ones that haven’t been broken.

However, this is not enough. As a society, we cannot let the legacy and active existence of the Native American people fade away. It is up to everyone, of every race, to help stop the mistreatment of native people in America by recognizing what happened in the past, and making sure that it can’t repeat itself.