Picture 1958 America: Blacks have not yet been granted the civil liberties enjoyed by Whites; many establishments, including public ones, segregate Whites and non-Whites; Black voting rights are not protected; and separate is equal. The civil rights movement is in its infancy.

Fast forward 60 years and the movement is now seen as a struggle of the past. And rightfully so. After all, it is 2018: the rights outlined in the Constitution and its amendments have reached all free citizens, assuming you don’t live in a U.S. territory; the Civil Rights Act of 1964 has officially outlawed traditional segregation; and separate has been deemed unequal. There’s even a court case to prove it.

But that judicial ruling, and many others just like it, is merely an illusion: misleading, yet seemingly irrefutable evidence that the fight for civil rights has been successful—and is now over. Don’t get me wrong, several boxes on the civil rights to-do list have been checked. But many others have been erased, rearranged or unrecognizably altered so as to give the impression that they no longer exist when really, they persist. Like invisible ink … only maybe not so invisible.

In 2016, Black males between ages 18 and 19 were almost 12 times more likely to be imprisoned than White males of the same age, according to a report from the Bureau of Justice. And, according to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), African Americans account for roughly 12.5 percent of drug users, but constitute 29 percent of those arrested and 33 percent of those incarcerated in state prisons for drug offenses. “Equal” isn’t so equal.

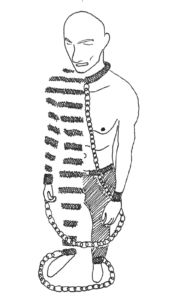

Let’s rewind again, this time a little further. In 1865, the 13th Amendment to the Constitution was passed by Congress, prohibiting “involuntary solitude, except as a punishment for crime” in a country that had heavily relied on slave labor for the past century. It was, by all historical standards, revolutionary. But this amendment—consisting of 32 carefully, and deliberately, placed words—included a very intentional loophole: prisoners were not exempt from forced labor. And so there remained an entirely legal way to preserve slavery, and the booming economy it fueled: mass incarceration.

Following the passage of the 13th Amendment, Blacks were systematically imprisoned. A set of laws—known as the Black Codes—unfairly targeted them by criminalizing actions which were completely legal. For example, they prohibited Blacks from leaving their places of “employment” and from assembling in the absence of a White person. According to the Bureau of Justice, Blacks constituted 13 percent of the U.S. population, but 29 percent of the prison population by 1880. These Black Codes, present in other forms (like Jim Crow laws), remained in effect until the Civil Rights Act of 1965, which brings us back to where we started. It seems as though the elimination of this discriminatory legislation is simply another checked box on our civil rights to-do list.

But if the Black Codes and Jim Crow laws were simply legal justifications for the unwarranted incarceration of Blacks, how do we classify the War on Drugs?

While the War on Drugs was waged under the guise of unprejudiced virtue, the fact is, in 2015, Blacks were almost four times more likely than Whites to be arrested for drug offenses, according to Brookings, a public policy organization. Drug usage across races was roughly the same.

But the most startling racial disparity of War on Drugs is the federal punishment for cocaine. A 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that 55 percent of crack cocaine users are White—a clear majority. But according to the Criminal Justice Policy Foundation, Blacks are over 21 times more likely than Whites to be incarcerated in federal prison for crack offenses.

This imbalance in the criminal justice system is simply another way society maintains the second-class status of Blacks at the will of an inherently flawed justice system. Slavery, unrecognizably altered.

But stopping at incarceration isn’t enough. No, it’s what happens, or rather what doesn’t happen, during and after incarceration that is detrimental to the advancement of racial equality in this country.

Education—including vocational training, literacy programs, English as a Second Language classes and other courses—is a crucial step in a prisoner’s reentry into society and future success, especially because lack of schooling is often correlated to incarceration in the first place. Those without a high school diploma are 47 times more likely to be incarcerated than peers with a college degree, according to GenFKD.

Education is the answer. According to RAND, inmates who receive correctional educational programs are 43 percent less likely to recidivate. But, instead of supporting instruction, California decided to cut funding for prison education programs by 30 percent in 2009. It’s as if the government went out of its way to ensure the protraction of mass incarceration.

Even when educational opportunities are available, the financial burden almost always falls on the inmate. With the exception of President Obama’s project to extend Pell Grant (a government subsidy for college) eligibility to 12,000 prisoners, if inmates wish to learn, they must pay. Considering the strained financial situations of many prisoners, learning seldom transpires. If quality education is a way out of the criminal justice system, we have sealed the exits.

And for those who manage to break free, a criminal record remains a significant barrier to employment. Employers often run background checks on potential employees and, not surprisingly, studies by the American Journal of Sociology in 2003 found that a criminal record reduces chances of employment by an average of 50 percent. Since then, an international campaign known as “ban the box” has worked to remove the check box on job applications forcing candidates to provide criminal history. The “ban the box” movement has gained traction in 30 states and about 150 cities and counties, but according to the National Employment Law Project, 20 of those states and 135 of those cities extend these laws only to employees of the public sector. The public sector makes up just 15 percent of the total workforce.

Institutional subjugation of Blacks has persisted through multiple passages of legislation, decades of government action, and years of failed intervention. So you don’t really have to picture 1958 America; we’re still in it.