The 21st century has conditioned us to an accelerated lifestyle. Email, automated bridge tolls and soon-to-be-released self-lacing shoes all stand as examples of our regular routines taking less and less time as the efficiency of modern technology improves. One of the frustrating exceptions to this rule, however, has emerged as an increasingly prominent part of our everyday lives: traffic.

We are all familiar with the feeling of helpless restlessness that comes from being stuck in a bumper-to-bumper traffic jam. Not a day passes without a classmate, colleague or family member complaining about how long it took to travel from one place to another. In the October Bark survey, almost a third of students reported spending 40 minutes or more in the car every day. But how much do you really know about traffic in Marin?

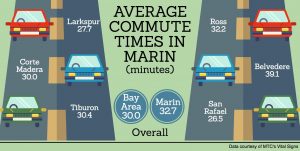

According to the Metropolitan Transportation Commission’s (MTC) website ‘Vital Signs,’ as of 2014, commute times, time spent in congestion and miles spent in congestion were at an all-time high in the Bay Area.

Derek McGill, planning manager at Transportation Authority of Marin (TAM), said that traffic in Marin is indeed increasing.

“Some segments of our Congestion Management Plan network have shown some slight improvements. However the main arterials like Third Street in San Rafael and Highway 101 have gotten worse,” McGill said.

The main factors that affect traffic are land use and the economy, according to McGill.

“A residential piece of land generates a different trip attraction and trip generation rate than something like a Target, that is likely to generate a lot of traffic and vehicle trips,” McGill said. “As for the economy, when it’s down we see less traffic on the roadways because people aren’t going shopping, they aren’t going out to restaurants, and a lot of them aren’t going to work sometimes.”

According to Dan Cherrier, a principal project delivery manager at TAM, Marin is forced to deal with a lot of highway traffic due to the fact that many trips aren’t possible without going on Highway 101.

“Most areas in the Bay Area, or even statewide, have local road systems that are right next to the highway, so the local traffic tends to stay on the local roads and regional traffic tends to stay on the major highway,” Cherrier said. “In our case, if you’re going from Sausalito to Corte Madera, you have no choice but to get on 101.”

Marin is a thoroughfare for a large amount of traffic with a final destination outside of Marin County, added McGill and Nicholas Nguyen, a principal project delivery manager at TAM.

“That’s not the case in a lot of other areas, where you have alternate routes. Everybody that has to go to Oakland, for example, typically goes through Marin County, and you see that in the morning commute with very heavy volumes on the 101 between Novato and San Rafael,” McGill said.

Another issue is that many people who work in Marin can’t afford to live in the county and have to drive in from other locations, according to Nguyen.

However, several projects are in the works which will help to alleviate the current levels of congestion.

TAM is currently working with Sonoma County and the state of California to complete the Marin-Sonoma Narrows project on Highway 101. Along with adding a third lane for carpool users, the latest phase involves making the section of the road near San Antonio Creek, which forms part of the boundary between Marin and Sonoma County, more flood-protected by raising the elevation of the roadway.

Part of the project involves putting more focus on preventing and managing accidents in that area, according to Nguyen.

“Since you can’t build new freeways very easily, what you have to do is use what you got more efficiently, and the efficiency in this particular case is ‘how do we prevent or at least manage traffic accidents once they occur?’” Nguyen said.

According to Cherrier, a third lane on the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge should also be open sometime next year.

English teacher Joe Gonzalez commutes to Redwood from El Cerrito and said he is excited about the possibility of an extra lane on the bridge to lighten evening traffic.

“That would open up for me more opportunities to be involved in school activities that are after school,” Gonzalez said. “Because it’s the only way to get to the East Bay without going all the way through Vallejo or without going through the city, it’s all about the functionality of the bridge and the amount of traffic that it contains.”

TAM is also funding pedestrian and bike-friendly pathways to schools in Marin as part of its Safe Routes to School initiative in an effort to decrease the number of cars on the road. According to an email sent out by Principal David Sondheim on Sept. 30, 62 percent of Redwood students drive to school in single family vehicles, meaning they drive by themselves or with other members of their family.

“We’ve found that 25 percent of the morning traffic is basically someone driving a kid to be dropped off at school here in the county,” Cherrier said. “We work really hard to get that number down by encouraging people to get to school some alternate way, by either bus or bicycle or walking or whatever it might be.”

https://vimeo.com/188003296Ramp metering lights will also be installed on a number of northbound Highway 101 on-ramps to regulate the flow of traffic during certain times of day. Though the project initially ran over-budget, it should soon be back on track once MTC finds additional funding, according to Cherrier.

Though some people are concerned that this may back traffic up onto local streets, the ramp meters are designed with a feature that is meant prevent this from happening, according to Nguyen.

“If [the cars] back up too far onto the on-ramp, the sensors detect that vehicle at the very end of the line and tell the computer ‘look, we’re almost about to back cars onto the local streets, why don’t you start metering the cars faster?’ to clear that on-ramp,” Nguyen said.

In the future, Nguyen predicts commute hours will continue to expand from the traditional peak periods of traffic.

“In the afternoons, instead of the kind of 4 o’clock or 5 o’clock surge of people going home, now it’s in between about 2 and 7 p.m.,” Nguyen said. “I think that trend will continue, because what we’re seeing is that people are more flexible in the times that they can start and stop work.”

McGill said he hopes to see major traffic relief on Highway 101 thanks to the SMART train, set to begin service in the spring of 2017.

English teacher Robert Winkler is exploring the idea of taking the train to Larkspur instead of driving from his home in Sebastopol.

“I have a hybrid that gets terrific gas mileage, and there’s a chance it might be cheaper for me to drive my car. It depends on how much the train is going to cost,” Winkler said.

Though Winkler tries to arrive at Redwood around 4:15 a.m. in order to skip the morning congestion, he still ends up commuting around 10 hours per week.

“I don’t think it’s been altogether good for my health at all,” Winkler said. “By the time I get home I’m exhausted; I have absolutely no energy. So not only am I sitting for hours, but then I have no energy to be active.”

According to Nguyen and McGill, TAM’s efforts to improve traffic conditions are limited due to the amount of funding they receive.

“At the end of the day, the solution to a lot of this congestion is being constrained by the lack of funding, whether that is through legislative actions at the governed level of not putting a particular priority on solving some of these issues or other things,” Nguyen said.

Nguyen added that there’s also the economic challenge of gas tax revenues diminishing as cars become more fuel-efficient.

“For great reasons, we’re building more efficient cars to preserve the environment, but since a lot of the transportation funding is tied to gas taxes at the federal and state levels, we’re making less money,” Nguyen said.

Though maybe flying cars are not the answer to Marin’s traffic problems, McGill said technology has a long history in the transportation industry and will play a part in resolving some of these issues in the coming years.

According to McGill, innovations to autonomous vehicles could potentially rewrite roadway capacity rules.

“If cars can talk to each other and they’re automatically sensored, the gaps between cars on the roadway reduce, potentially allowing for a platooning effect which can increase the amount of roadway capacity available for more cars,” McGill said. “If it’s a public vehicle, the issue of parking goes away in a lot of cases, allowing more space to be available on the roads for lanes and through-travel rather than parking.”

Nguyen said he is proud of what TAM has accomplished as Marin’s official Congestion Management Agency and of what they are currently doing to improve traffic.

“Between building new infrastructure, investing in different modes of transportation such as these travel demand management programs that we have which get people out of their vehicle and into another mode of transportation, addressing future needs such as planning for State Route 37 which is an older corridor up in the North, I think we’re doing everything that we hope to be doing,” Nguyen said.