Period Poverty: More exhausting than the cycle itself?

Disclaimer: For the purpose of this article, people who menstruate are referred to as women, however, it should be kept in mind that not everyone who has a period cycle identifies as a woman.

May 3, 2023

With $18,000 you could buy a car, put a down payment on a house, further your education or even establish a robust retirement plan. However for people who menstruate this money is often invested in necessary purchases of period products made throughout their lifetime. These products range from pads, tampons and menstrual cups, to period-specific underwear and more. But no matter the product, they don’t come cheap.

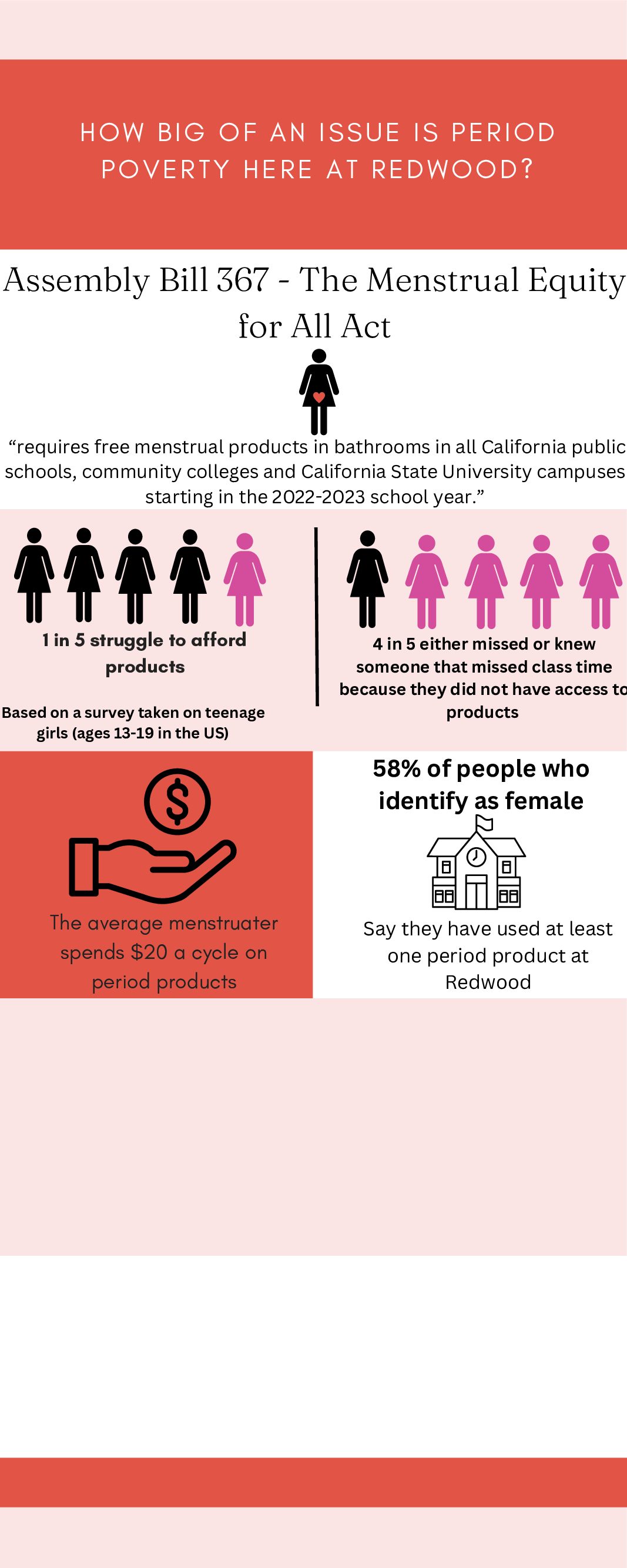

According to the National Organization for Women, the average woman spends about $20 on feminine hygiene products per cycle and given that most adults have between nine and twelve periods a year, the money soaked up by these products accumulates quickly.

As a well-established issue within society, lacking period care has been coined “period poverty.” The exact meaning is described as “the struggle many low-income women face when trying to afford menstrual products.”

The financial burden women and girls face due to the necessity of menstrual supplies can be viewed across the world. According to the World Bank (an International Monetary Fund) a study in 2022 showed an estimated 500 million individuals across the globe lack access to menstrual products and adequate facilities for menstrual hygiene management.

This statistic doesn’t exclude those in the United States struggling with these issues. Given how ethnically diverse the United States is, issues concerning period poverty can stem from a lack of education in certain communities, among the lack of access. Pediatrician Jessica Hollman working in the Canal District in San Rafael said she sees this often.

“What I see more of isn’t a lack of supplies, but a lack of education on different menstrual products girls can use. I know many girls that stop doing sports once they start menstruating. For example, [many girls] ask for permission to skip swimming in school during their periods because they are afraid to use tampons,” Hollman said.

Since many don’t use tampons, Hollman said she tries to find ways to help her patients feel comfortable with using these products given how little they know.

“Especially for patients that are athletes, I really try to educate them on tampon use. I tell them that their period should never stop them from doing anything.”

The infrequent education provided to young girls in the community about menstruation can spike the rate of infections as girls struggle to take care of their bodies. This combined with the high prices of period products makes the need for education and lowering the prices more dire.

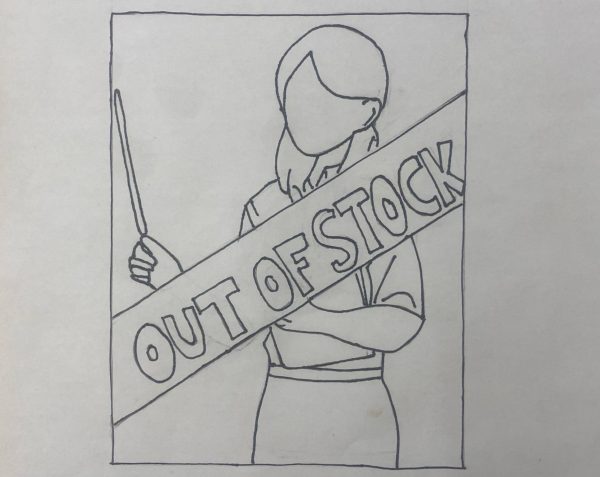

Since the recent COVID-19 pandemic many industries have struggled to meet the demand of their consumers for many products. The same case went for menstrual products as availability dropped and prices rose. The normalization of high prices for period products means the majority of menstruators overlook the blatant inflation.

However the pre-pandemic prices weren’t much better, potentially as a result of the 1995 “pink tax” bill.

The pink tax magnifies the price of products that individuals buy on retail shelves regardless of resulting gender-based discrimination. Examples of this are as common as something like laxatives. Two boxes of laxatives on the shelf are identical with the same brand, ingredients and use but one box is labeled for women. The only difference is that the price for the pink women’s box is raised by 84 cents compared to the normal box. The seemingly insignificant financial burden women encounter upon purchasing items can add up to spending more than their male counterparts.

However, those living in California will no longer have to worry about the pink tax. New Bill No. 1287 authored by Assembly Member Rebecca Bauer-Kahan prohibits businesses from pricing identical products differently based on their target market. The bill was signed Sept. 27, 2022, by Calif. Governor Gavin Newsom and went into effect on Jan. 1, 2023 after viewing the clear unfair financial treatment women have been facing since the 1990s.

“This type of arbitrary gendered pricing has no place in California. It’s past time to ensure price equality,” Assembly Member Bauer-Kahan said in an article published by the Columbia Broadcasting System staff.

California has also passed Assembly Bill No. 367, the Menstrual Equity for All Act, which was signed by Gov. Newsom, on Oct. 8, 2021. The Menstrual Equity for All Act will “require free menstrual products in bathrooms in all California public schools, community colleges and California State University campuses starting in the 2022-2023 school year.”

Given the new California law, Redwood installed its free menstrual product dispensers in the restrooms this year to ensure it agreed with state mandates. So far, it seems it is being put to use. According to a Redwood Bark survey, 58 percent of people who identify as female say they have used at least one product supplied in the restrooms.

Redwood itself has been distributing free period hygiene products for around seven years through the Wellness Center. Magdalena Maguire, a Wellness

Outreach Specialist who works at Redwood High School, is in charge of restocking them.

“Frequently students come in to grab pads or tampons, I’d say at least twice a class period. So ten or 15 times a day students come in to grab pads or tampons,” said Maguire.

Nevertheless, sometimes students don’t just need products for the school day and have to come in more often because they don’t have these supplies at home.

“That has happened here, where I see [people] coming in more frequently and I always ask them, ‘Hey, do you have these supplies at home?’ Sometimes [the answer is] yes. Sometimes it’s no. Either way, [I say], ‘Why don’t I just give you a box?’,” said Maguire.

Given the dire need for menstrual products, it begs the final question: Should the price of menstrual products be lower, or possibly free?

For Redwood freshman Stella Belluomini, the answer is simple.

“I think [menstrual products] are way too high priced,” Belluomini said. “When men are doing their finances, unlike women, they don’t have to think about that added burden.”

Considering California has made changes to the way period products are sold and distributed, many think that the fight is over. However, California is one of only 15 states that have exempted period products from sales tax. Despite these changes, there are still states that are continuing to drain money from menstruating individuals’ pockets, forcing them into more impoverished areas.

Period poverty encompasses a multitude of gender-related issues that requires multiple steps towards a solution. For starters, expanding California’s bill diminishing the pink tax to a federal level. Secondly, doing our part to educate those around us. The average woman spends around 2,535 days menstruating, so they get to know their body pretty well. However, for a preteen child who is menstruating for the first time, the lack of products and education surrounding the subject could throw them into the deep end fast. By normalizing and educating the world about period poverty, people who menstruate can use that $18,000 toward bigger things in their life than overpriced menstrual products.