To tip or not to tip

The modern expectation and its impacts

May 5, 2023

The spun-around iPad at a checkout blinks expectantly. Ten percent, 15 percent or 20 percent? Since its introduction to the United States (U.S.) in the 1800s by European travelers, tipping has allowed Americans to express their gratitude with dollars. But now, with rising prices and a heightened awareness of the often poor conditions in the industry caused by tipping, the tides have shifted and the longstanding expectation of tipping is faltering.

The spun-around iPad at a checkout blinks expectantly. Ten percent, 15 percent or 20 percent? Since its introduction to the United States (U.S.) in the 1800s by European travelers, tipping has allowed Americans to express their gratitude with dollars. But now, with rising prices and a heightened awareness of the often poor conditions in the industry caused by tipping, the tides have shifted and the longstanding expectation of tipping is faltering.

Originally, tipping was meant to serve as a means to reward good service and to offset the high labor costs of running a restaurant. However, the widespread reliance on tipping can perpetuate a variety of inequalities. According to an analysis by Eater of U.S. census data, white servers make more in tips than other racial groups: the median hourly tip for white servers from 2010 to 2016 was $7.06, compared to $6.08 for Latinx servers, $5.57 for Black servers and $4.77 for Asian servers.

Ann Tepovich, an Advanced Placement (AP) Economics teacher, said that according to labor economists, tipping can provide a justification for lower wages.

“An employer can say, ‘Well, you’re going to make this [wage] plus tips, so I don’t have to raise your base salary.’ When I had a job in high school, I earned less than minimum wage because I earned tips. And that is really, to me, somewhat exploitative, because there’s no guarantee [of income],” Tepovich said.

At the root of the continued reliance on tipping in America is the lower status of tipped work. According to Tepovich, this results in lower wages for restaurant employees and an increased reliance on tipping to close the gap.

“[In other parts of the world], maybe you leave a few coins or you round up, but [tipping] is not necessarily expected,” Tepovich said. “In [socialized European] countries, workers tend to have a stronger voice… If you have a homogenous view that all work is good work, you tend to see higher wages, even for base-level jobs.”

As an understanding of the low wages of the restaurant industry has spread, so has the expectation of tipping — beyond restaurant checks and dine-in services, into the realm of touch screens at coffee shops and takeout. Tepovich said that the rise of touch-screen tipping has created a new reality: tips based on guilt rather than service, especially in businesses where tipping previously wasn’t the norm.

“They’re calling it tipflation — that you feel pressured [to tip more] because that person is standing there… I have two dynamics pushing me: One, the nice barista, standing there, staring at me. Two, that I don’t feel [the purchase] as much. I’m using plastic or my Apple watch. So it’s both of these psychological dynamics that are forcing this,” Tepovich said. “Maybe we’re tipping less each time, but we’re tipping more on things that we never used to tip for.”

Tipping can present a moral as well as an economic dilemma for customers. Cassie Davis, who worked as a waitress throughout her college and graduate school years, has tipped more ever since working in the restaurant industry, as she understands the difficult conditions and low wages for waiters.

“My experience led me to generously tip most of my adult life because I knew what a hard job it was,” Davis said. “In different states at the time, there was a really low hourly rate, so you wouldn’t make anything if you didn’t get tips.”

Despite her history with tipping, Davis says that she’s experienced the phenomenon of tipflation as well.

“[Tipping has] put the [burden] of paying a living wage to employees onto the consumers,” Davis said. “The big con of depending on tipping is that it’s creating the issue of [the lack of a liveable wage], so that the employer can get away with not paying their employees a living wage.”

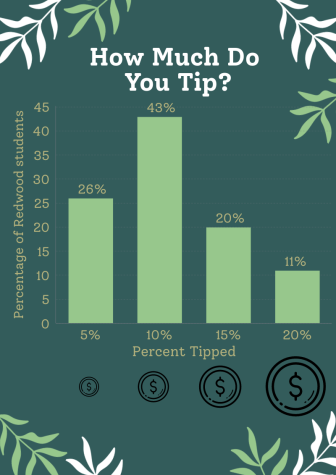

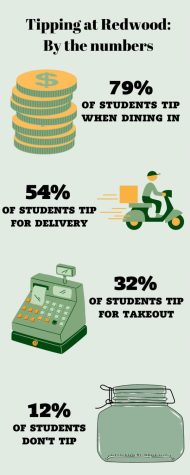

The changing landscape of food ordering platforms — dine-in, delivery and takeout alike — has also influenced the rise of tipflation. According to a 2023 Bark survey, students tip differently depending on where they’re getting food; 82 percent of students tip for dine-in services and 53 percent tip for delivery, while only 33 percent tip for takeout.

Debra Hilleboe, a local parent, said that although she’s accustomed to tipping 20 percent for dine-in, she’s felt a recent pressure to tip more for pick-up and delivery.

“[Touch screen tipping] has now set an expectation that everywhere, you have to tip,” Hilleboe said. “You feel more guilty now because [for takeout]… when you’re checking out, it asks you to tip. And so you feel like, ‘Am I supposed to be tipping? But I’m not really getting service, so why am I tipping?’”

According to a 2023 Bark survey, nearly half of students tip 10 percent for take-out, while only one in ten students tip 20 percent. Molly Goldstein, a sophomore who works at Mag’s Local Yogurt in Larkspur, says that her job has led her to tip more, regardless of the type of restaurant.

“Even if it’s the smallest thing, I still will tip because I know it makes [employees] feel good,” Goldstein said. “Maybe they’ve had a long day and they’ve dealt with rude customers, or [they’re overworked] or maybe they haven’t been getting all the tips… I know that they’re doing a good job, even if it’s not the best customer service.”

Within restaurants as well as outside of them, tipping can lead to a variety of inequalities, as Tepovich explained.

“Right now, tipping isn’t really fair if you’re in the kitchen. It’s great if you’re the server, and then the server is responsible for tipping out the bartender, tipping out the host and tipping out the kitchen,” Tepovich said. “Restaurants find they have the hardest time finding kitchen help because the pay is lower and they don’t get tips.”

Many restaurants, in response to the variety of inequalities created by tipping, have tried to find alternatives, such as raising prices or including mandatory service charges in the bill. These service charges, intended to increase wages for kitchen staff, can be put towards benefits and can address the uncertainty of tipped wages. For restaurants under the Bay Area-based Bacchus Management Group, eliminating tipping and creating a service charge in its place led to the payment of certain kitchen staff increasing by more than 50 percent. In the Bay Area, restaurants such as Comal in Berkeley, Zuni in San Francisco and Flea Street in Menlo Park have all switched to a tipping-free model.

However, going tipless hasn’t always ended well. In the case of San Francisco’s Bar Agricole and Trou Normand, both eliminated tipping, resulting in a loss of servers due to a decrease in their pay. Both restaurants reverted back to tipping in less than a year. Tepovich spoke to a similar instance in New York, in which the higher-end restaurant chain of Union Square Hospitality Group chose to raise the prices on their menu in order to phase out the expectation of tipping.

“Their thinking was that it could be more equally distributed, because then the restaurant can share those increases in profits by paying the workers more,” Tepovich said. This decision, however, was met with backlash from customers — a result of the loss of consumer choice when switching to a tipless model.

“I think it’s a lot of the psychology of how we feel as the consumer. We want to feel like we are in control,” Tepovich said. “You sit down and look at the menu and you’re like, ‘Are you kidding me, charging $22 for a burger?’ People really pushed back [against raising prices]. But in the end, after you tip, you’re still probably paying $22 for that burger.”

As the prices of goods and services rise, it can be hard to sacrifice even a dollar. However, besides tipping, there are many other ways to show gratitude to workers; even the smallest tips and level of respect can make a difference.

“[The tip] could be 50 cents, but if five people come in and tip 50 cents, then that’s a certain amount,” Goldstein said. “A little goes a long way.”