Columbia University didn’t want me and that’s just fine

Last December, I submitted my final college application. The application was to Columbia University, an Ivy League institution in New York City ranked as the number two research university in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. I, like many students who applied to these highly ranked colleges, believed that gaining admission to an Ivy League university was a shot in the dark for any applicant, regardless of how monumental their achievements were in high school, and thus was disappointed, but not surprised, to receive a rejection letter in March.

What was surprising to me was the number of comments I received from people in my life: well-meaning sympathy, suggesting that my rejection could be due to the color of my skin (I’m white) and insinuating that perhaps I would have been admitted, if I were another race.

While no one will ever know if that’s actually true, we do know that for years, selective and prestigious universities like Columbia have discriminated against people of color in admissions processes through implicit and explicit bias. The recent push for increased diversity within university classes still has a way to go before it can dismantle those practices. Blaming schools’ efforts to create space for people of color in predominantly white institutions in increasingly competitive admissions cycles only masks the true problem: white people are afraid of losing their shortcut to the front of the admissions line — something they never should have had to begin with.

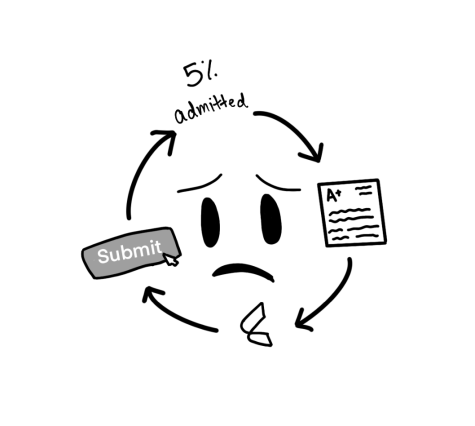

The cycle goes like this: every year, students around the world apply to college. In recent years, the number of college applicants has skyrocketed, driving acceptance rates at many universities into the single digits. Affirmative action is not to blame for plummeting acceptance rates; a self-perpetuating cycle of fear is responsible.

The first efforts to create a more equitable admissions process came in the form of affirmative action. According to the Law Information Institute at Cornell University, affirmative action is “a set of procedures designed to eliminate unlawful discrimination among applicants, remedy the results of such prior discrimination and prevent such discrimination in the future.” Today, college admission officers often implore a similar practice called “holistic admissions” when deciding who to admit or deny in each application cycle. “Holistic admissions” shares some of the same principles as affirmative action and is based on the idea that a student’s GPA or test scores do not create a complete picture of the student, that an admissions officer can look at an applicant’s identity — such as their race — to get a more detailed look at the applicant’s life. These practices have been challenged by lawsuits attacking the holistic admissions processes, namely at Harvard, Yale, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill, University of Michigan and the University of California. What these lawsuits show is how blame is doled out during these ultra-competitive admissions processes on the universities for admitting more students who are less privileged because of their marginalized identity.

There’s reason to believe that affirmative action and holistic admissions is working as intended. Since 2000, college enrollment has increased across all race demographics, with the most dramatic increases in Black, Hispanic and Indigenous American/Alaskan Native students. Increased levels of education in a society is good news no matter what. Still, drastic improvements for marginalized communities result in even greater societal progress as studies show that compared to those with high school diplomas, individuals with bachelor’s degrees earn about $20,000 more, across all racial demographics.

But does progress for minority students really come at the expense of white students, as the people who made subtle and not-so-subtle insinuations about my rejection from Columbia asserted?

No. This could not be further from the truth. There is plenty of room for all students who want a college education. Thousands of institutions in the U.S., and abroad, offer high-quality instruction that results in employment. Want to find those places? Take off the blinders that many middle, and upper-middle-class families wear as they chase their college dreams, the blinders that keep their eyes trained on the top 20 schools ranked in the U.S. News and World Report. People put on these blinders because they are afraid, unsure of where they or their child will end up after high school. And last year’s admissions rates at the top 20 only compound that fear. Increased applications don’t translate into more seats in freshman classes at these schools. Headlines also prey on nervous students and parents — twice, I was sent Douglas Belkin’s Wall Street Journal article “To Get Into the Ivy League, ‘Extraordinary’ Isn’t Always Enough These Days,” a profile on a high-achieving white student who was shut out of the Ivy League, supposedly because of her “demographic profile” and a few B’s sophomore year. She’s still headed to a great school; Arizona State University, studying business, but not the most prestigious university she had expected for herself. But prestige is a factor that has very little, if any, impact on the quality of education one might receive at a particular college or university, or the success one might achieve professionally, particularly if one is raised in a middle or upper middle-class family. Thousands of people graduate each year from low-ranked universities, community colleges, trade schools, etc. and move on to fulfilling lives and careers.

So where does that leave students applying for the nation’s most selective (or most rejective) universities? Where is the admissions hurricane that is caused by rising applications, holistic admissions, an uncertain future and an ongoing pandemic land?

If I were to venture into the eye of the storm, where it is calm and quiet, absent the snarky comments made by classmates, the well-meaning but misguided advice of family and friends and the pressure I put on myself to define success as narrowly as a 3 percent admissions rate, I might see quite clearly that I’m going to be just fine without Columbia University on my resume. And I might even feel delighted that there were so many qualified applicants of so many ethnicities, backgrounds and experiences, that there was no room for me.

Abby Shewmaker is a senior at Redwood and a Senior Staff Writer for the Bark. Previously, she has served as a News and copy editor. She loves her guitar,...