In the past month from February 28 to March 20, the US Border Patrol has detained more than 11,000 unaccompanied migrant children at the U.S.-Mexico border. Until recently, the shelters’ capacity was reduced by almost 40 percent due to the virus, forcing Joe Biden’s administration to reopen Donald Trump-era child migrant facilities. Simultaneously, Biden attempts to uphold the promise of more humane treatment of migrants compared to Trump.

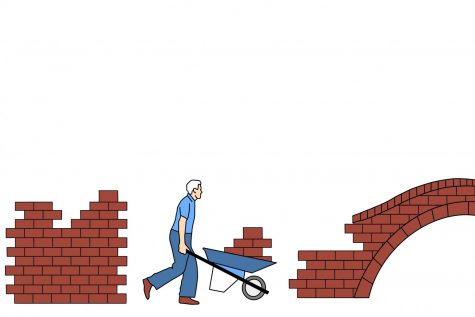

In recent administrations, issues concerning border control, deportation and citizenship have taken center stage. As seen within the past 76 days, the shift of presidential power has already had a profound effect on the U.S. immigration system. Not only are the current policies being changed during a pandemic and a surge of migrant children, but they are also confronting immigration from a less deterrent angle. Although the course might seem uncharted, Biden may learn from the legislative successes and failures made by Barack Obama and Trump.

Border patrol

The Obama administration asserted control over the U.S.-Mexico border by expanding the detention capacity. Criticism arose, however, when children were detained in these facilities for beyond the 72-hour mandate. To balance out the harsher detention policies, Obama invested $750 million in Central American countries to manage the influx of immigrants at its source. In terms of preventing immigrants from entering the U.S., Trump succeeded in sealing off the border. Still, many Americans, including English as a Second Language (ESL) teacher Deborah McCrea, did not believe this approach yielded success.

“I think it’s our duty as a country to give people a safe place … Trump just tried to shut everything down… [For Trump] to [detain] children in cages really disturbed me and I feel outraged and ashamed at what was done in the name of our country, and to a certain extent is still being done,” McCrea said.

Trump instituted policies that limited the number of asylum seekers allowed to enter ports and discouraged families from entering. However, the separation of families came from a rule after COVID-19 was declared a public health emergency. This rule, Title 42, expelled — or rapidly turned away — all migrants who crossed the border, including unaccompanied children. What was meant to be a precautionary measure against spreading disease caused the displacement of children, as the U.S. sent them to Mexico instead of their home countries. Under the program known as Migrant Protection Protocols, informally known as “Wait in Mexico,” 25,000 asylum seekers who were forced to wait along the U.S.-Mexico border are starting to be gradually processed by the U.S. government. While living in San Diego in 1989, McCrea protested to demilitarize the border after seeing its inhumane conditions.

“I feel so sad for the people who, under Trump, were placed along the border because I know how dangerous those places can be, especially for vulnerable individuals. They’re in this crazy limbo where they were told they had to wait in Mexico,” said McCrea. “I think [a better solution] is for people to wait for the processes to occur in the U.S. because most people are coming here because they know somebody here. There’s a whole immigration theory about how there’s the first person who comes and then more people follow, so [it’s very rare for people] to come by themselves.”

(Courtesy of Bruno Sanchez-Andrade Nuño)

Deportations

Obama, named by critics as “deporter-in-chief,” was notorious for the high rates of deportation during his presidency, deporting nearly 3 million foreigners over his 8-year term — an estimated 1.7 million of them had no criminal record. These figures were in large part due to Secure Communities, a program created by the Bush administration that used fingerprint identification to detect immigrants in local jails. Once identified, undocumented immigrants were taken into custody by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents and then deported. The expansion of Secure Communities created opposition that argued too many foreigners were being deported for only being accused of minor offenses such as traffic violations. In response, Obama replaced this program with Priority Enforcement, which focused ICE resources only towards the most high-profile criminal cases. To decrease the high rate of deportations, many cities, counties and local agencies limited police aid to ICE by passing sanctuary policies. Still, this widespread fear of deportations persists and was further intensified by Trump’s rhetoric and policies to vett the status of immigrant populations. Michelle Levin-Meer, an immigration lawyer and Redwood parent, points out the risk non-citizens face.

“In the United States, if you’re arrested, and you can’t afford an attorney, you can get a public defender to represent you. If you’re detained by ICE for an immigration violation [where] you didn’t commit a felony or crime, that would get you a public defender. There is no right to an attorney. I think that’s really wrong, so I have thought about maybe [transitioning] into some defense of people who are just caught up in the system and don’t have a lot of options,” Levin-Meer said.

Nonprofits can offer representation for immigrants arrested by ICE, but Levin-Meer says their help isn’t adequate.

“I’m on a bunch of listservs for immigration lawyers, and [nonprofits] are always calling for [lawyers] to go down to the Texas border because there are tons of people who are arrested right there and they need representation. They don’t have enough [lawyers.]” Levin-Meer said.

In the 2020 debates, Biden called it a “big mistake” to have deported hundreds of thousands of people without criminal records during his time serving with the Obama administration. His proposal of reversing the 3- and 10-year bars could compensate, though. Currently, anyone in the U.S. illegally for 180 days or less is barred for three years from returning and those for more than one year are barred for 10 years. Levin-Meer believes Biden should remove 3- and 10-year bars, one reason being the policy exiles individuals who have overstayed their VISAs.

“People are married to an American, they’ve had kids and they’re just stuck here. They can’t come out of the shadows because if they do, they could be sent back to a country that maybe they’ve never even looked at. It’s a mess… So, if we got rid of the 3- and 10-year bars, that would be huge,” Levin-Meer said.

Citizenship

The process of obtaining citizenship has become increasingly difficult over the last few decades, in part due to the new requirements Trump created for green cards and the asylum restrictions for migrants at the U.S. southern border. Levin-Meer has experienced frustration with the evolution of immigration law practices in the past two decades.

“When I first started practicing immigration law, it was pretty procedural. If you wanted to get a VISA to come here, you showed A, B and C, and you’d get the VISA. There were always outliers and things that went wrong, but usually, it worked. What I’ve seen in the past 20 years is immigration become almost like an adversarial law practice; we fight all the time now,” Levin-Meer said.

One of Biden’s goals is paving an 8-year pathway to citizenship for 11 million people living without legal status. Unlike bills seen in the past three decades, it intends to remove family-based immigration restrictions and expand worker VISAs. Although Levin-Meer doesn’t know whether or not it’s realistic, she supports the idea.

“If Biden could actually push through something that would help people who have been here for that long — some of these people have been here for 20 years — and help them to do something to adjust their status, it would be so good for the country,” said Levin-Meer.

Senior Nico O’Neill has several family members who emigrated from Mexico and became citizens after getting work VISAs and then green cards. Although the process went smoothly for them, O’Neill says that gaining citizenship can become a challenge if the applicant cannot pass their background check or speak English, not to mention if they entered the U.S. illegally.

“I think that immigration has made the United States as great as it is because [of the] diversity. But, the problem is finding the balance of how many immigrants the U.S. can really take because the U.S. can only support so many people; there’s already [10.5] percent of Americans below the poverty line,” O’Neill said. “We have to find a good balance and also make it easy for people to immigrate [here] legally so they don’t have to [immigrate] illegally because that can be dangerous and lead to [the] splitting up [of families].”

The political polarization in America certainly doesn’t benefit the concord of partisan issues such as immigration, but O’Neill believes there is hope.

“I think that in a lot of places the [political] divide isn’t as big as some people say it is. I feel like the media is a big part of the problem [because they label] people as either Democrats or Republicans. A lot of people share similar ideas and they’ll [change opinions] depending on the scenario they’re put in,” O’Neill said.

Choosing which battles to fight in such a multi-faceted agenda will be difficult for Biden, but McCrea believes that he must address immigration issues immediately.

“Now is the time. I don’t think [immigration] should be anything less than a huge priority because it affects so many individuals… We look at [immigration] as a policy or as something very abstract, but each decision affects thousands if not more actual human beings, many of whom live in our orbit. I think it should be a priority and as soon as possible while [Biden] has the majority,” McCrea said.