How the new coronavirus has plagued the world with racism

March 16, 2020

“What are we gonna do about a totalitarian dictatorship where it’s okay to sell live virus-infected bats in open-air marketplaces and then have business travel and tourists travel between that country and the civilized world?” guest economist Don Luskin said on the Fox Business Network’s Trish Regan Primetime show.

“China Is the Real Sick Man of Asia,” read the title of a Wall Street Journal opinion piece.

“We urge citizens to stay away from Chinese supermarkets, shops, fast food outlets, Restaurant, [sic] and Business,” a Facebook message shared by an office assistant and receptionist in Assemblywoman Mathylde Frontus’ Coney Island office read. “Most of the owners went back to China to celebrate the Chinese New [Year] Celebrations. They are returning and some are bringing along the Coronavirus. Rather be safe than sorry.”

In the past four months, COVID-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus, has spread globally and induced increasing death tolls. Along with the spread of the disease, America has seen an increased spread, or perhaps a resurfacing, of anti-Asian sentiment in the United States. A recent Bark survey found 52 percent of Redwood students have seen or experienced racism towards people of Asian heritage as a result of recent COVID-19 outbreaks. Merriam-Webster defines xenophobia as “fear and hatred of strangers or foreigners or of anything that is strange or foreign,” something that has become widely prevalent when directed at Asians due to the new coronavirus. However, this virus should not justify xenophobic actions.

Throughout the U.S., Asians have experienced unwarranted acts of xenophobia. CNBC found that some Uber and Lyft drivers have been refusing service to people who appear to be Asian. CNN described an incident in which a man assaulted an Asian woman wearing a face mask and another case of racism in which a man declared, “Everything comes from China because they’re fucking disgusting.” An article in USA Today covered the significant decreases in business for Chinese restaurants in America following the outbreak of the epidemic.

On Jan. 30, the University of California, Berkeley’s health services center posted a list of “Common Reactions” to the epidemic, listing xenophobia towards Asian people as one of the bullet points. Social media platforms such as Twitter, Instagram and Tik Tok supply an influx of posts criticizing Chinese people for their eating habits and hygiene while joking about the importance of staying away from Asians.

In light of these xenophobic actions, Nancy Messonnier, MD, director of the CDC National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, released a statement saying, “Do not assume that if someone is of Asian descent, they have coronavirus,” a seemingly obvious statement, though one that now apparently needs to be said.

The correlation often drawn between those of Asian descent and disease dates back to the 19th century. A KQED News article found that Chinese migrants underwent humiliating medical inspections at Angel Island not required of Europeans at Ellis Island. During the outbreak of the bubonic plague in San Francisco, anti-Chinese sentiments led to the Chinatown’s quarantine despite objections from residents, according to PBS. These actions unjustifiably targeted Chinese people. In the current world we live in, the racism involved in these historical instances typically appears blatantly obvious. When it comes to present-day issues, however, people get swept up in residual prejudices despite their striking similarities to historical issues.

Though not as visible prior to the coronavirus, many of these implicit biases towards Asians prevail. Racism is always prevalent whether acted upon or not and much of the time, it remains dormant, resulting in a false idea that in an increasingly tolerant world, historical prejudices face eradication. However, during high tension situations such as disease epidemics, racism reveals itself.

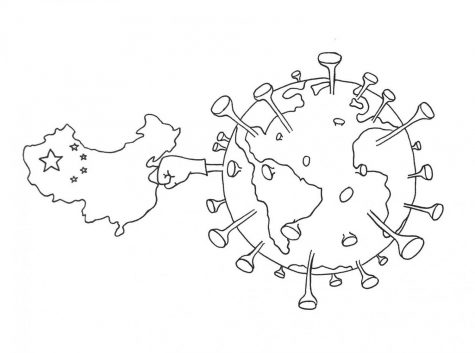

According to Forbes, there is no proof of COVID-19 targeting a particular socio-demographic group, instead spreading once the virus has reached a specific location and therefore disproving the seemingly pervasive idea that avoidance of Chinese people will decrease infection risk. As the disease does not discriminate between races, it can only mean people are discriminating without justification.

According to CNN, the virus is believed to have originated in a Wuhan wildlife market, and due to coronaviruses’ zoonotic nature (meaning it is transmitted between animals and people), many of the memes found on social media poke fun at Chinese diets consisting of animals Americans typically find unappealing or untraditional. As a result, these posts tend to blame the coronavirus on the people consuming these animals. However, cuisine norms are vastly different in every culture, and to target one race for their food would be hypocritical. For example, in many Jewish and Muslim communities, pork is forbidden, while in the U.S., pork is consumed frequently and without giving second thought to the cleanliness of the animal. Blaming the coronavirus on Chinese cultural cuisine is equivalent to blaming the swine flu on pork consumption; in both cases, correct handling of the animals was most likely the issue, not the food itself.

Fear of infection is justified, but racism towards a singular demographic as a result of that fear is not. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Gilbert Gee, a professor at UCLA’s Fielding School of Public Health, said, “We have this tendency to confuse people who are sick with entire groups of people, and that’s what makes it discriminatory.” This issue did not originate with the coronavirus, also appearing in the discrimination towards Africans during the Ebola outbreak and Mexicans during the H1N1 swine flu. The commonality between these cases and the current coronavirus epidemic is the lack of evidence proving an increased susceptibility to infection of a certain race.

In a world that appears to nurture tolerance, it is essential to not allow singular events to reverse progress. Rather than succumbing to misinformed racism, education is crucial to ensure the prevention of discrimination.