When high school student-athletes consider continuing their sport in college, many immediately picture themselves playing for a Division I school. After all, what athlete wouldn’t want to contribute to a team at the highest collegiate level? While reasons for playing Division I can range from athletes aspiring to play professionally to wanting to partake in something they love, there is another underrated and perfectly feasible option for student-athletes of the latter desire: Division III sports.

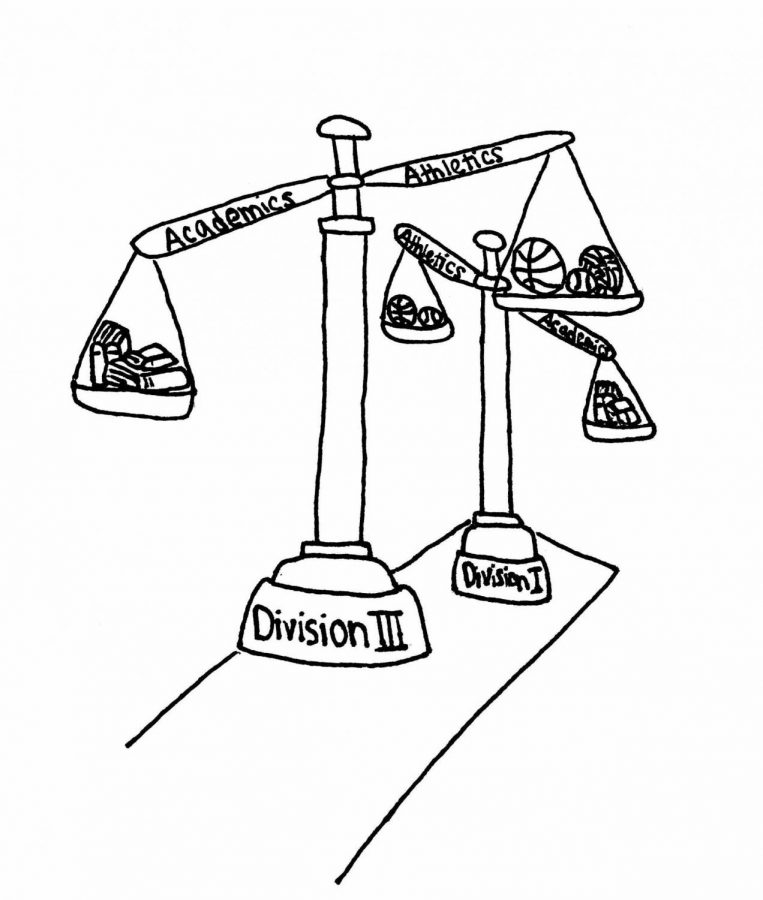

Because Division III does not offer athletic scholarships for many top athletes, an academic scholarship is the ultimate goal. Despite this, Division III sports are still competitive, but also provide more time for athletes to participate in the “student” aspect of the student-athlete experience. In fact, many of the most highly rated academic schools in the country are in Division III, such as Amherst, Johns Hopkins and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, according to the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA). Division I schools can also be a great fit for some student-athletes; however, for those who may not be looking to play past college, Division III is an excellent option. Therefore, any stigma surrounding it is unwarranted, as they are still a highly competitive division.

College athletics, regardless of division, are elite. According to a study conducted by the NCAA, only 3.4 percent of men’s high school basketball players play in college and over 40% of college players play at Division III schools. As only the very top athletes in every sport continue playing at the collegiate level, any college player is extremely talented in the sport they are pursuing.

Compared to Division I, where athletes often receive preferential treatment by college admissions, it can be more difficult for students to be accepted into a Division III school if they do not achieve test scores or grade qualifications. This is due to admissions valuing grades equally or more than athletic talent. Therefore, in some ways, gaining the opportunity to play for a particular Division III program can be much more difficult than for many Division I or Division II schools. At the same time, for students who are attempting to gain entry to a top academic school, being a strong athlete can give them an edge among a highly competitive applicant pool.

In addition to Division III and Division I, Division II also offers student-athletes a chance of playing their sport at the NCAA level. While Division II is similar to Division III in the way that the school size is typically smaller than Division I, the academic demands of student-athletes at Division III tend to be greater than Division II because there are no athletic scholarships. When a student attends a college on an athletic scholarship, they have an obligation to fulfill athletic requirements first and prioritize school second. However, athletics are no excuse for lack of academic performance. Although Division III is not as competitive because they do not receive the very best recruits like some Division I and Division II schools do, it is still a highly demanding environment, often with much greater academic demands to balance.

Nonetheless, Division III’s “students first, athletes second” mindset allows students to have a more flexible schedule with practices, games and classes, especially throughout the off-season. According to the NCAA, many coaches even encourage students to take a semester off to study abroad. The intense athletic environment at some Division I schools can lead to a limited amount of time for academics and other college experiences outside of their sport.

While not all Division I athletes feel this way, according to the Associated Press, when playing at the Division I University of California, Los Angeles, former basketball player Ed O’Bannon stated, “I was an athlete masquerading as a student… I was there strictly to play basketball. I did, basically, the minimum to make sure I kept my eligibility academically so I could play.”

According to the Stack, an athletics and nutrition-based focused publication, a former soccer player at the Division III Pomona College, Natalie Babaresi, had the opposite experience of O’Bannon’s.

“Playing soccer at Pomona has not only challenged and improved my soccer skills but also has deepened my love and appreciation for the game. What’s more, playing at the Division III level has permitted me to be a student-athlete in every sense of the word, meaning that my studies and academics take precedence over my athletic responsibilities, instead of the reverse,” Babaresi said.

Though seasons at Division III colleges are somewhat shorter, players still have a demanding and fulfilling schedule. For example, while a Pac-12 softball team might play 50-55 games before postseason, teams in the NESCAC (Division III) still compete in 30-35 regular season games and work out throughout the school year.

Although Division I and Division II programs have their drawbacks, one particular advantage are their athletic scholarships, which are not available at Division III schools. Without these scholarships, families with a lower socioeconomic status are at a disadvantage because they are less likely to be able to afford to put their kids through four years of college, creating an incentive for many to aim for Division I or Division II. However, despite the rules holding them back from giving out athletic scholarships, according to the NCAA, 80 percent of all student-athletes in Division III programs receive some form of academic grant or need-based scholarship, and institutional gift aid totals $17,000 on average.

Playing Division I college sports offers many exciting benefits, including the highest level of play and athletic scholarships. That being said, Division III athletics are also compelling, albeit in different ways. Offering a healthy balance between athletics and academics for students looking to compete collegiately, Division III schools strengthen the true identity of a student-athlete.