Why do, like, people like to say “like” so much?

December 18, 2019

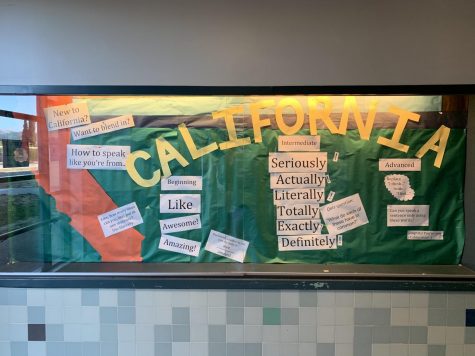

Emblematic of California teen culture, the word “like” has become one of the most versatile words in the English language. It can be used to replace a verb, stall for time, describe a scenario, describe an action, express approval––the list goes on. Grandparents might defile it as a representation of the ignorance and informal nature of young people, while teenagers may not notice it. But regardless of anyone’s opinion, the reasons for why we use “like” and how it affects conversations are far more than what meets the ear.

According to an article in The Atlantic, the word’s origins lay in Old English with the word, “gelic” which meant “with the body of.” This is a form of comparison between two objects––the first manner in which “like” was used. Soon enough the “ge” fell away, and the remaining “lic” morphed into “like.”

The word continued to evolve for centuries, but the most distinct origins of its modern uses lay in the Beatnik generation of the 1950s. According to Britannica, Beatnik was a media stereotype to describe the “Beat” generation of the 1950s and 60s, very similar to the hippies that emerged in the following decade. Beatniks were associated with drug use, spirituality, artistic freedom and defiance of social norms. They were additionally known for their occasional use of the word “like.”

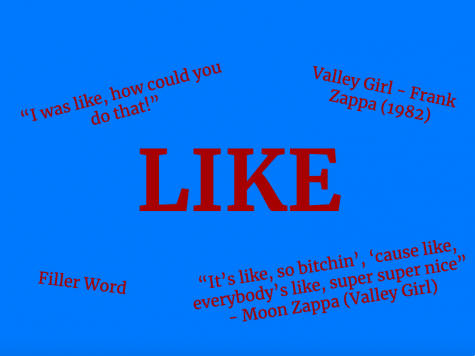

According to Language Dossier, a website that aims to provide insight into the English language by describing different aspects of it, the 1980s witnessed the arrival of valley-girl speak, and with it came the explosion of the word. The insertion of “like” between words and clauses became widely used, and 80s musical artist Frank Zappa released a single called “Valley Girl.” In the song, Zappa’s 14-year-old daughter filled the radio with the airheaded speech of a “valley girl,” the portrayal of a stereotypical teenage girl from southern California. Two of the lyrics are, “‘cause like everybody’s, like, super super nice” and “It’s, like, totally disgusting.”

The use of the word greatly increased after the track and despite a decrease in the 2000s, it is still prevalent today, according to Language Dossier. Due to stereotypes such as the one displayed by Zappa, overuse of the word has come to signify stupidity or an airhead personality. However, junior Chloe Swildens doesn’t view its use as such, but rather just an annoying habit.

“I don’t necessarily think it’s a bad thing, but it can definitely get overused and excessive to a point where you get annoyed by the person who’s overusing the word,” Swildens said.

English teacher Steve Hettleman expressed similar sentiments as Swildens, seeing excessive use of the word as a distraction.

“I pay attention to [when someone says like], so I tend to not listen to the content of what they’re saying too much,” Hettleman said. “I don’t want to, it’s just that that’s what happens to my brain…and so it just draws my attention away.”

While it is easy to discover the word’s origins and how its overuse affects conversations, what its use says about society and American culture remains unknown. English teacher Dr. Fiona Allan hypothesized that Americans use of “like” as a filler word reflects broader cultural trends.

“Their thoughts are not as grounded or rooted. So they need to connect their thoughts or ideas that are still forming, whereas somebody who might be more prepared doesn’t need to do that. Or even just somebody that’s more comfortable with what they’re saying,” Allan said.

In an interview with The Independent, Michael Handford, professor of Applied Linguistics and English Language at Cardiff University, explained the interactional and cognitive functions for why people use filler words.

“The interactional function is to do with politeness. If you invite somebody to a party and they say no without any of those markers they will appeal rude probably. If you say ‘um, well, you know, sorry’ it makes it much more polite,” Handford said.

The cognitive function applies when the speaker is describing something complex, or is at a loss of what to say.

“As speakers we are often aware, if we speak too complexly the listener might not understand. We use these items to help the person process what we are saying… If someone asks you a difficult question, then while you’re scratching your head for an answer you are probably going to be using more of them,” Handford said.

Allan, who previously lived in Mexico City, noted that California and Americans are not unique in our use of filler words.

“I think every language has its fillers. I know in Spanish everybody would say ‘este,’ instead of ‘like’ or ‘um,’” Allan said

Both Hettleman and Allan proposed solutions to reduce the frequency with which people say “like.”

“The way to go about [change] is probably just to draw attention to it for people, [but] not in any kind of punitive way or punishing people for it. It’s a subconscious thing. So drawing people’s attention to it might raise awareness and cause people to try to stop doing it,” Hettleman said.

Allan focused more on what she perceived to be a possible root cause of its overuse.

“There’s a certain awareness and to have that mind-mouth connection is important. In our culture today, people speak without as much thinking they should probably be doing, and it’s good to be thoughtful,” Allan said.

“Like” is but one example of how the English language is constantly evolving along with society. In the future, “like” could become extinct or be replaced by a completely different word. “Like” has traveled across time and vernacular from the 1950s Beatniks to the modern valley girl. It may seem unprofessional today, but “like” is, like, pretty interesting.