Why are we accepting demonstrated interest in the college admissions process?

December 13, 2019

As college admission decisions draw closer for early applicants this December, I have had some time to reflect on my own application process. While the stress of researching, reaching out to admissions counselors, touring schools, writing essays and filling out applications was all consuming, it is finally over. As my parents have been nice enough to constantly point out, applying to college is much easier nowadays. Back in the day, they had to hand write essays and mail them to colleges. Now, it’s quicker to add more schools with my Common Application, University of California application or Coalition portfolio to apply and send off my information. But that privilege also comes with drawbacks such as the reliance on demonstrated interest, where students show colleges they want to attend that school, as a major factor in the admissions decisions.

More specifically, demonstrated interest is when a student displays their interest to a college through signing up for mailing lists, attending information sessions, touring the campus and requesting interviews once they apply. This can help a university maintain a higher yield rate (the amount of students who are accepted and end up enrolling), as they can be sure the accepted students are seriously considering their school. With a wide range and high volume of applicants, colleges are looking for any details to help narrow the process and ensure the students they accept want to go to their university.

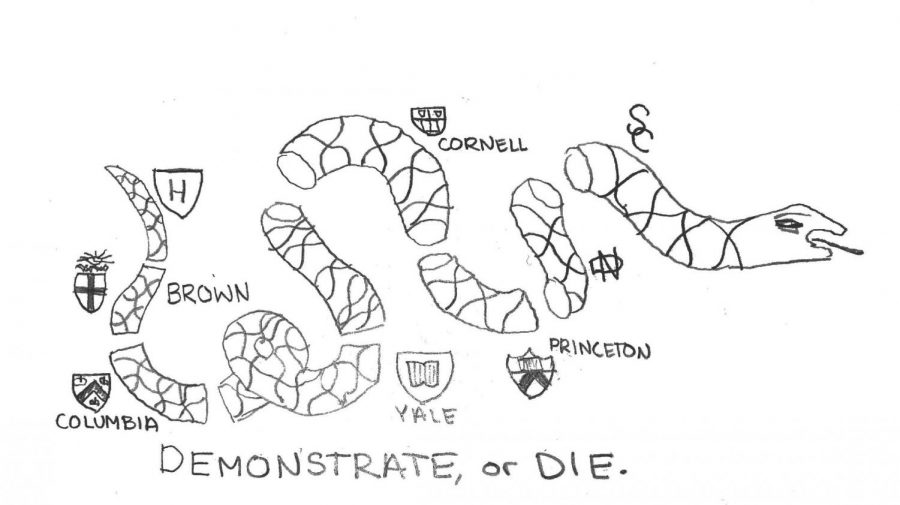

Demonstrated interest has become a large deciding factor in college admissions as schools receive more applications every year. Due to the increase in applications, acceptance rates have begun to decline at the top prestigious universities across the United States. According to the Pew Research Center, “[Acceptance] rates have fallen because prospective students are applying to more schools than they used to, while the number of available spots for them has grown more slowly. In absolute numbers, schools are making more admission offers than before, but not enough to keep pace with the soaring number of applications.” Applying to college is easier than before but with an increasing population, both the application and admissions processes have changed. This increase in applicants and competitive admissions is why most admissions departments consider demonstrated interest in order to help decide if students should be admitted or not.

Colleges need demonstrated interest to increase their yield rates and appear more prestigious. U.S. News, which ranks colleges in lists such as “best national universities” and “best liberal arts colleges,” publishes a list of the “highest yield universities” every year as a way to show prospective students where other students are eager to enroll. This year, Harvard University topped the list with an 82.8 percent yield rate, just above Stanford’s 81.7 percent. Although this may be a statistic for an admissions office to brag about, it doesn’t take into account the student’s perspective and the ways it could affect applicants in the college admissions process.

Rather than turning into a “numbers game” to have the best statistics nationwide, colleges and universities should be focused on educating future generations. Fixating on a yield rate and using demonstrated interest to maximize said rate is missing the point of college and higher education’s purpose, which should concentrate on the needs of students, not admissions.

The high costs and unnecessary time it takes students to demonstrate interest is a key issue with the application process. Many schools have the supplemental application essay prompt “Why our school?” that asks applicants to explain their demonstrated interest. For students looking at schools as far away as those on the East Coast, this can take a toll on applying seniors, making the application process longer, more difficult and expensive. It means missing high school to tour college campuses and possibly falling behind in classwork and homework, as well as paying for travel, accommodation and other expenses on the visit.

This privilege doesn’t extend to everyone, and if a student can’t take time off of school or parents cannot afford to send their child on a trip, it becomes incredibly difficult to stay competitive and write a demonstrated interest essay that will stand out in the large applicant pool. Emailing professors and counselors and taking virtual tours online might be the best alternative option to make supplemental essays shine, but they will not stand out as much to an admissions officer compared to a student who visited the college and had a meaningful experience.

On the other hand, there is validity to colleges wanting to know which students are genuinely interested. It has become challenging in recent years to be an admissions officer, according to Dr. Adriel Hilton, a lecturer at Northeastern University with first hand experience in admissions.

“There are recruitment goals to meet, numerous personalities to deal with, typically a heavy travel schedule during peak recruitment periods…and always a lot of paperwork and digital media to maintain,” Dr. Hilton stated.

With more applicants and diversity in terms of what students are accomplishing, it’s hard to make such difficult decisions for students, so many schools fall back on demonstrated interest.

Using demonstrated interest as a factor in the college admissions process is not only unfair, but it is primarily in the self-interest of most universities and doesn’t benefit the applicants themselves. If colleges were able to let go of being highly ranked by publications such as U.S. News and understand that students will come to them if they are truly interested, it would be beneficial for both the school and students. As a high school senior and an aspiring college student, I can say from first hand experience that the current process of demonstrated interest is not only broken, but unfair and unrealistic.