Our view of celebrities has turned to guilty until proven innocent

May 30, 2019

Conversations feel like a minefield nowadays. I mentioned an actor I really enjoy to one of my friends and she responded, “Oh, but he raped somebody.” I was shocked. How had I not heard of this? “When?” I asked. “Someone just accused him yesterday,” she replied. Well, is he really a rapist then? If the case goes to trial, and he is found guilty, then yes, he is a rapist. But if a woman he knew 10 years ago accuses him of rape, there is no guarantee of his guilt.

I truly admire that the attitude in pop culture, politics and our society in general has switched to one of believing victims because ultimately, most victims do not lie about rape, nor should we treat accusations as such. Unfortunately, I do believe that the immediate trust of victims has gone too far. Most often with celebrities and other famous figures, especially concerning allegations of sexual misconduct, individuals are immediately assumed to be guilty prior to a just and fair trial. This topples two of the core values of our advanced society: the right to the assumption of innocence and the right to a speedy and public trial.

A person’s celebrity status can interfere with an unbiased court verdict, as shown with the sexual assault investigation of professional wrestler Conor McGregor. McGregor was accused of rape in December of 2018, but The New York Times didn’t report on the event until March 26, 2019. This is because in Ireland, McGregor’s home country where the allegations took place, laws do not allow the press to divulge sensitive information during ongoing rape trials, including the defendant’s name, until they have been convicted, according to the New York Times. If the news media violates these laws, punishments include damaging claims of libel along with an infraction of privacy laws. In this circumstance, The New York Times obtained insider information on the case and published the material without permission from McGregor or the Irish Justice System.

Dr. Conor Hanley, a law lecturer at the National University of Ireland Galway, put the reasoning for the law into understandable terms.

“Society’s concern for victims should not come at the expense of the defendant’s right to a fair trial,” Hanley said.

One of the biggest faults with the judicial and societal response to rape and sexual assault allegations is the intense and scrutinizing media attention they receive. Outlets muddy the normally clear waters of the law by involving public opinion, as seen in The New York Times’ reporting on McGregor, or even public organizations such as C-SPAN’s live coverage of the Anita Hill/Clarence Thomas case and the Christine Blasey-Ford/Brett Kavanaugh trial. When pressure from uninvolved civilians begins to permeate the justice system, jurors, attorneys and even justices fall prey to the temptation of catering to the masses. With outside interference, the final verdict of guilty or not-guilty is now not entirely accurate or unbiased.

In addition to pressure on justice officials, public trials also create intense scrutinization of the accuser. This is clearly seen in cases mentioned before, such as Anita Hill/Clarence Thomas or Christine Blasey Ford/Brett Kavanaugh. According to her biography, Hill received intense backlash in the form of verbal harassment, reputational destruction and even hate mail after her testimony in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee. Blasey-Ford overcame similar obstacles with attacks on her credibility and mistrust of her motives. An atmosphere such as this makes it hard for victims to come forward and share their story and ultimately discourages the majority of rape and sexual assault victims from actually facing their assaulter. According to Joanne Belknap, a sociologist, criminologist and professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, 90 percent of rapes in the United States go unreported. Victims would feel much safer coming forward if their cases were treated with the sensitivity and privacy they deserve.

As I stated earlier, many victims of sex crimes are telling the truth and we should always approach the topic with a sense of sensitivity and sympathy. In fact, according to Belknap, five percent of rape accusations are found to be false, a figure based on college studies. However, as we do with most trials of law not concerning celebrities, we must address rape trials in an unbiased way free of assumptions one way or another. Victim believability is important, but so is the assumption of innocence of all of the accused. Innocent until proven guilty is an essential privilege of our democracy that serves to uphold our basic individual freedoms, preserving our status as a democratic nation.

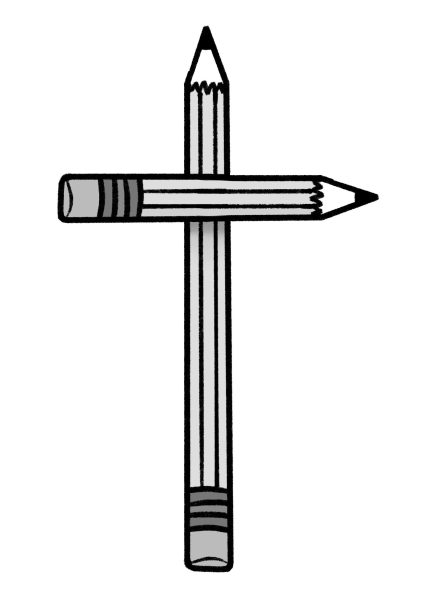

How should we go about making rape trials more accurate? To begin with, the United States should adopt similar laws to Ireland, in which the identity of those accused of rape is protected until the verdict is released, especially in an age as controversial as the #MeToo movement, with the public disagreeing on who or what to believe. Clearer lines would be drawn between the truth and fabrication if the emotion was avoided with the inclusion of names or professions. In addition, Dr. Hanley suggests informing jurors prior to rape trials about the nuances of rape or sexual assault cases. Hanley argues that educating jurors on the misleading “rape myths,” such as the fact that many rapists are previously acquainted with the victim, will ultimately lead to a more unbiased and accurate verdict.

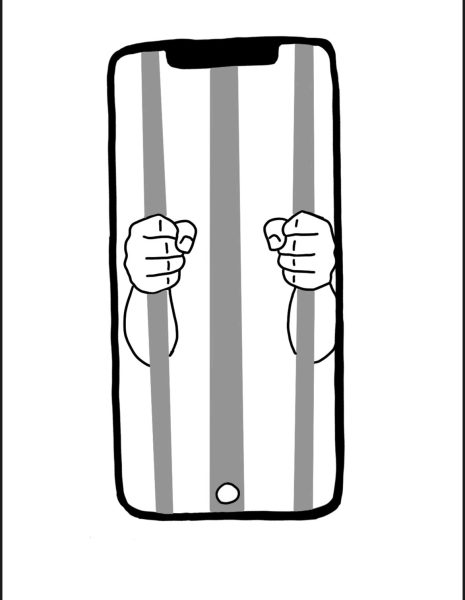

If we as a democratic society want to continue to preserve our basic rights and privileges, we must adapt to the changing times that technology and news media create. Although reporting has provided us with juicy gossip on our favorite celebrities and famous individuals, the pursuit of justice outweighs our craving for private information.