How college admissions offices allow lies to slip through the net

February 25, 2019

Friends and family members huddle around an eager prospective college student at a computer. One click, a few moments of fear and anticipation and then, a burst of screams, cries and excitement. This is a college acceptance reaction video.

Thousands of these videos swarm media sites like YouTube and attract millions of views. According to YouTube, some of the most viewed decision reaction videos come from students at the T.M. Landry College Preparatory School in Louisiana, with students opening acceptance letters from Columbia, Harvard, Stanford and other elite universities.

After receiving some of my own college acceptances, I have personally experienced the rewarding feeling of knowing that my hard work has paid off. But what if my college acceptances weren’t based off of my accomplishments, but instead a bed of lies? That’s the reality for many graduates at schools such as T.M. Landry College Prep, as college admissions officers don’t put enough effort into reviewing many components of an application to check for accuracy and truthfulness.

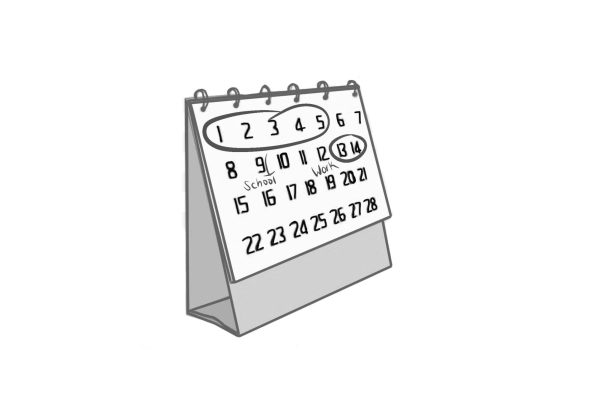

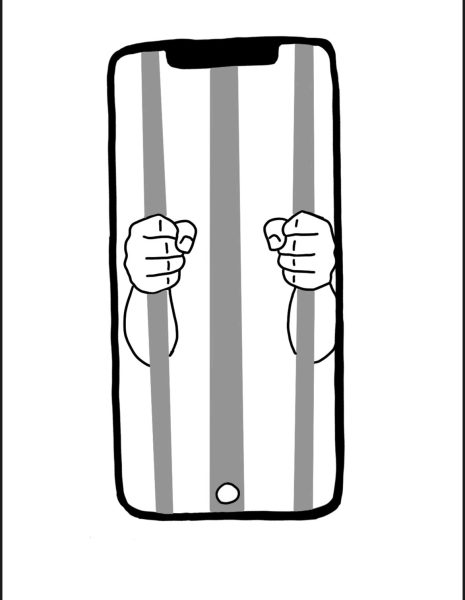

According to The Wall Street Journal, many of these selective universities read a prospective student’s entire application file in less than eight minutes on average. After this initial reading, applications are flagged with either admit, deny or waitlist, and 85 percent of files are never reviewed again.

Eight minutes to review my admissions file is an insult. Eight minutes is what it took me to write the leading sentence for my Common Application essay; it’s hardly enough time to read through an applicant’s personal information, demographics, grades and test scores, let alone the multiple several-hundred-word essays tied to an application. In the past four years, I’ve spent roughly 6,000 hours studying in school and 4,000 hours on extracurricular activities, not to mention the five months it took me to fill out my applications and the seemingly endless hours of homework every day. Is eight minutes truly enough time to review all of my hard work throughout my high school career? No wonder officials from T.M. Landry were never caught.

The private school, founded by former salesman and teacher Michael Landry and his wife, boasts a 100 percent college acceptance rate for its students and guarantees that working-class minority students will be put on a path to college graduation. While the Landrys’ mission laid out a promising end result, they tried to achieve that in an unscrupulous manner—through lies, intimidation and even abuse.

According to a recent investigation by The New York Times, the T.M. Landry School officials falsified students’ transcripts and accomplishments and encouraged students to write college application essays about fake hardships based on racial stereotypes.

While several admissions officers and college counselors from across the country say that the Landry case is extremely rare, it doesn’t eliminate the fact that this information slid past numerous readers from the nation’s top colleges. This is a result of colleges failing to fact-check and properly looking into an applicant’s official documents and extracurricular activities.

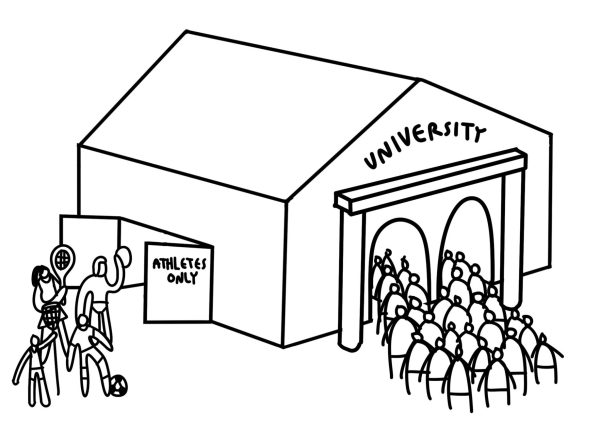

In an interview with The New York Times, Jim Rawlins, the admissions director at the University of Oregon, commented that essays are often read carefully, but extracurriculars are rarely verified.

“If [applicants] say they were on the football team from ninth to twelfth grade, who’s going to check it?” Rawlins said in the interview.

There’s a clear answer to that question; it’s the admissions officers’ job to verify these activities. They simply can’t rely on the honor system when it comes to such a competitive environment and assume teenagers will always do the right thing, especially if creating a white lie could get them into college.

Instead of taking a further look into the claims made by applicants, many admissions officers rely on their own experience and intuition to spot inconsistencies within an application. Katharine Harrington, vice president of admissions at the University of Southern California, affirmed this tactic in an interview with the New York Times.

“If each component is not all pulling in the same direction, it kind of becomes a red flag,” Harrington said.

In order to successfully and thoroughly look through college applications, admissions offices need to change their review policies. This could be done by hiring more staff members or lengthening the review process by pushing application deadlines forward.

The University of California (UC) has also adapted to a new system that tries to discourage students from trying to falsify or exaggerate their accomplishments and should serve as an example to other universities around the country. According to The Mercury News, every December, one month after the UC application deadline, approximately one percent of UC applicants (roughly 2,200 randomly selected freshman and transfer applicants to keep it both equitable and manageable for the admissions staff) are sent an application verification inquiry. This request asks the selected few for evidence to support claims made in their four Personal Statement essays and in other parts of the application, including honors and awards, extracurricular activities, financial and medical hardship, employment and even family death. Failing to verify their claims or respond to the request results in having one’s application being withdrawn.

In an interview with Mercury News, Han Mi Yoon-Wu, admissions coordinator for the nine UC campuses, said, “We value integrity … students need to know that they might be selected, and they should make sure that everything on the application is accurate.”

Surprisingly enough, the UC System is the only higher education institution in the country that does this, according to Mercury News. If other colleges would simply use the UC system as an example to adapt their review process, there would be a lower chance of these mistakes and a lower tolerance for schools like T.M. Landry College Prep and other individuals who try and cheat the system.

Receiving rejection and deferral decisions from universities are hard to swallow on their own. But what makes it much worse is that with the flawed review process, I could have easily lost a spot to another student who embellished and falsified parts of their application, a deed completely hidden in admission officers’ blind spots. Adjusting the application review method would not only make the college admissions system more equitable but also discourage students and officials from lying on applications.