Legacy favoritism does no favors for most

December 22, 2018

An applicant with a perfect SAT or ACT score, 4.0 unweighted GPA, rigorous course schedule, a history of community service, a summer internship and leadership experience under their belt is a seemingly perfect college applicant. They’re the kid that all of their classmates ask for help, the student that all the teachers talk fondly of and the one that everyone says is going somewhere. However, one box that’s left unchecked diminishes all of this achievement and as a result, might leave a qualified applicant with a rejection letter. That box is legacy status and serves as the root of inequality for many private colleges’ admission process that prioritizes familial connections over the caliber of students in a process that should be based purely on merit.

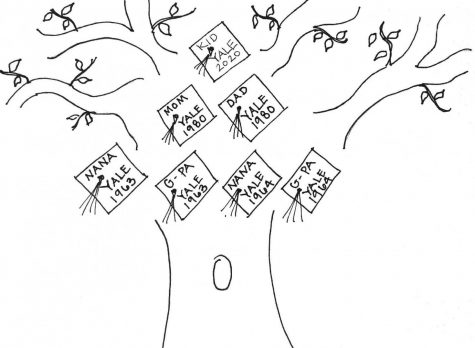

According to the Wall Street Journal, legacy applicants at Harvard University are five times as likely to be admitted than non-legacies, and at Stanford the admissions rate for legacies is two or three times higher than the general population, according to the Stanford Daily. This blatant favoritism of children of the educated elite has not only been drawn up in court as a part of the Students for Fair Admissions vs. Harvard case, but also has called into question the greater inequality across a majority of the collegiate system. According to the Wall Street Journal, in a study of 30 elite colleges, legacy students were 45 percent more likely to be admitted into a highly selective college or university than non-legacy. Because legacy is considered in applications at 75 percent of the top 100 research institutions and liberal arts colleges in the United States, according to College Transitions, this inequality is consolidated in the elite halls of colleges and universities, as opposed to lower-ranked schools. This results in discrimination against high-achieving, lower-income applicants whose parents may not have attended a top college or even college at all, further perpetuating the cycle of inequality that has resulted in such a gaping disparity between the rich and the poor.

Standardized testing is a pillar of the admissions process and also contributes to this inequality of educational access between the rich and the poor. Across high-achieving high schools, the SAT and ACT are complex processes, often including tutors, practice tests and hours of studying. Consequently, several students at Redwood, a school ranked in the top thirty of California high schools, are legacies to elite schools and are able to take part in such rigorous preparation for standardized tests, because they often have parents who are extremely invested financially and psychologically into their children’s college process. However, for all of the disadvantages a student without wealthy parents faces before college applications are due, the inequality reaches an even greater level within the admissions office. According to the Wall Street Journal, being a legacy is equivalent, in admissions value, to a 160 point gain on the SAT (on a 1600 point scale) and about a three point advantage on ACT. Additionally, according to The Atlantic, 38 colleges, among them five of the Ivies, had more students from the top one percent of the nation’s income than from the bottom 60 percent. This demonstrates that the importance of a checked legacy box stretches beyond just breaking a tie between two equally qualified applicants. The unfair advantage legacies have in college admissions highlights a blatant bias towards the children of the elite over the less fortunate students, and the disregard for the morality that comes with that favoritism.

Why should the accomplishments of an applicant’s parents be considered in a process that is otherwise based on merit.The answer most supporters of this biased system give is money. Alumni and legacies often claim that by allowing an admission advantage to students of graduates, a greater sense of loyalty is fostered, and therefore brings in more donations, bettering the school in the long run.

However, not only is this logic immoral, but the reasons behind the claim are inaccurate. According to the U.S. News, two of the top eight U.S. schools with the largest endowments are MIT, with an endowment of $14.8 billion, and Texas A&M, with over $10 billion. Incidentally, both of these highly-funded schools banned legacy-based admission over a decade ago, disproving the common justification that favoring legacies is necessary to uphold the school’s prestige.

The college admissions process shouldn’t be a contributor to the disparity that results from such early educational and economic equality, but instead should be a moral system that helps to equalize this disparity by being based on academic merit as opposed to legacy status.