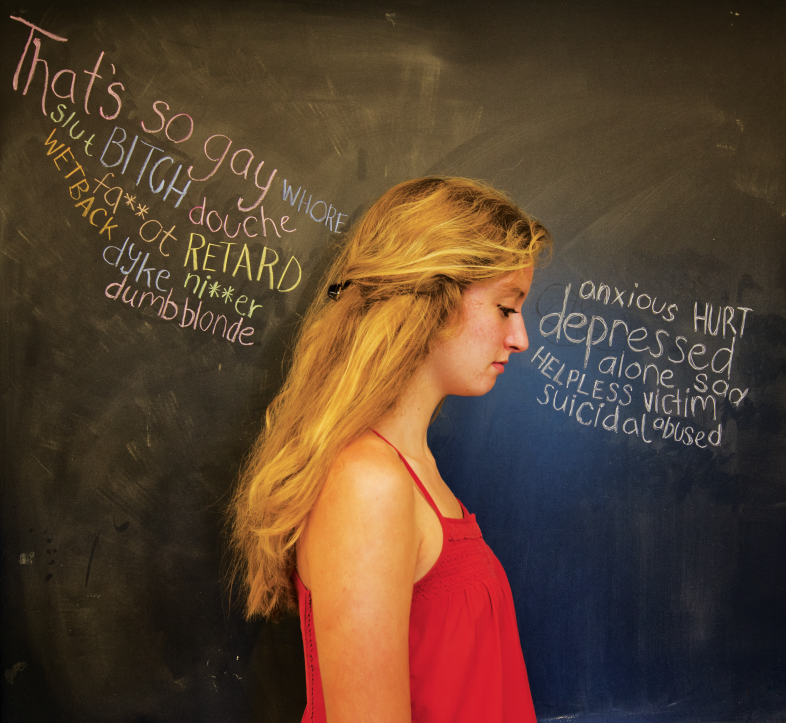

Bullying. The word is imposing, uncomfortable, and after years of anti-bullying assemblies, almost cliché. While statistics show that targeted, physical bullying has decreased in past years, verbal harassment has slid into its place. But now, the line between offensive speech and verbal bullying has blurred.

The Bark asked Caroline McNally and Tanisha Hook, two seniors who are friends, to discuss their opposing views on what they define as the bullying of gay students. McNally, a member of the the Gay Straight Transgender Alliance, said that the recurring use of the phrase “that’s so gay” is a form of bullying, regardless if it’s used to target someone or just in casual conversation.

“It doesn’t matter if you’re gay or not,” McNally said. “If people say ‘Oh, that’s so gay,’ it’s like saying ‘that’s stupid,’ and ‘gay’ shouldn’t be substituted for a bad word.”

Hook, who has gay family members and was accused of being a lesbian in middle school, said that she finds the phrase almost natural in teenage conversation and very rarely intentionally offensive.

“I don’t think people are going around the halls saying, ‘Oh, that’s so gay’ in front of a gay person,” Hook said. “It’s sort of like [the word] ‘retarded’ – it’s sort of a habit that doesn’t really mean anything. I’m not saying it’s right, because it’s not. I still think it should be stopped.”

Hook said that fellow students accused her of being a lesbian in middle school because she occasionally held her friend’s hand. Because of her experience, she said that she views high school as a much more accepting place, particularly for LGBT students.

“I do think that high schoolers don’t assume things as much [as middle schoolers],” Hook said. “I see girls all the time holding hands and in middle school it’s like, ‘Oh, that’s so gross,’ but in high school it’s like, ‘Oh, they’re just friends.’”

McNally, on the other hand, said that she classifies anything spoken about in a negative manner as bullying. She said although people are entitled to their opinions, it’s disrespectful to express them in a way that can be interpreted as offensive.

“You can have opinions,” McNally said, “but when you start to voice them negatively, it becomes bullying.”

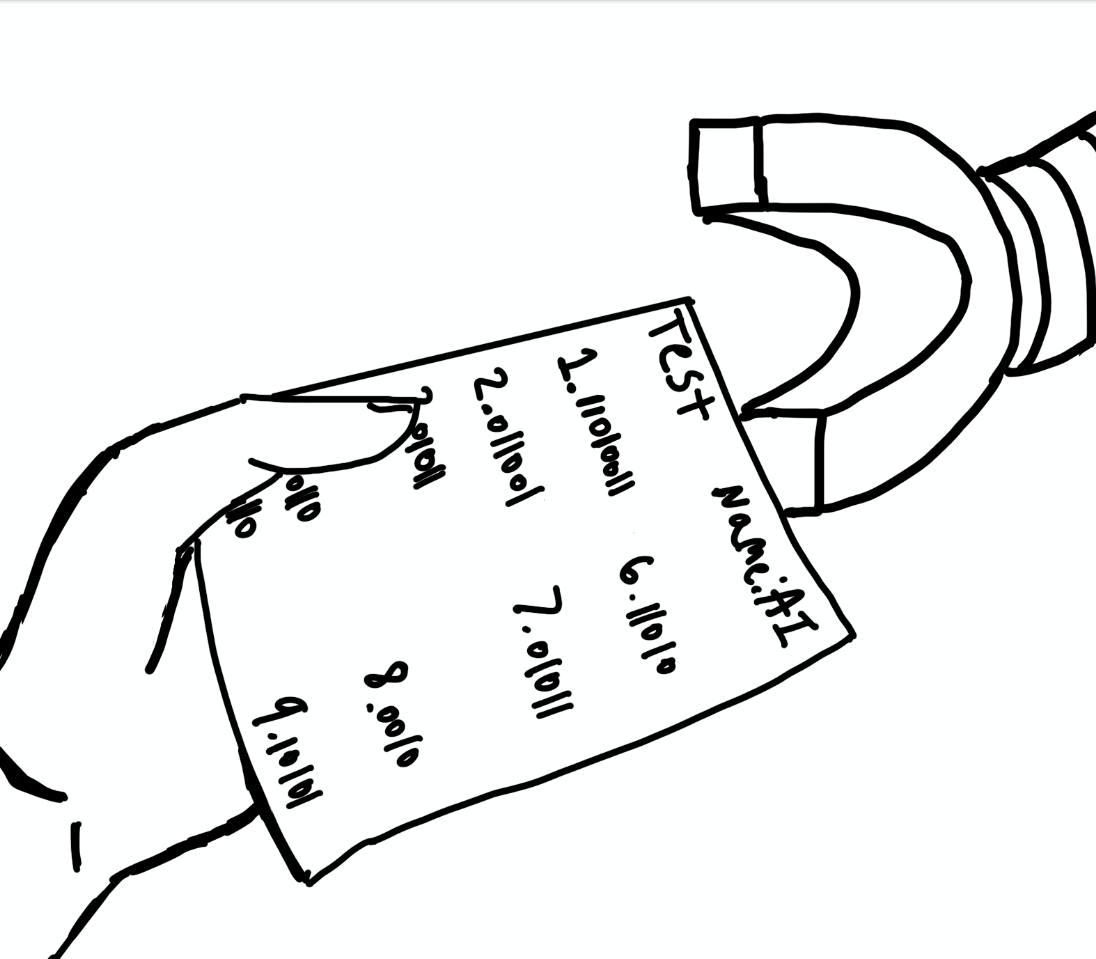

In October, the Marin County Youth Commission (MCYC) conducted a survey that found that homophobic language was the most frequent form of verbal harassment heard at Marin County high schools, as 85 percent of respondents heard anti-gay slurs.

According to the December Bark survey, sexist comments or derogatory terms towards a specific gender, such as “bitch,” are heard slightly more frequently at Redwood than anti-gay slurs.

In contrast, less than three percent of students reported being physically harassed in the MCYC survey.

When asked if they define sexist, homophobic, and racist comments as bullying on the December Bark survey, most respondents, 42 percent, said “a little bit.” Twenty-seven percent of respondents defined the language as bullying and 24 percent did not.

Like McNally, local clinical psychologist Dr. Mary Lamia said she thinks that bullying happens every day without much commotion. Lamia said that bullies do not just communicate with words, but also with looks and facial expressions.

“If a bully is walking down a hallway with a confident step and looks at a person in a particular way, a lot of times with a facial expression of disgust, that will change the other person,” Lamia said. “That in itself is language, too. A facial expression.”

According to Lamia, bullies are very skillful at humiliating people, even if they do so subconsciously.

“It doesn’t really matter what words they use, as long as it’s triggering shame in the other person,” she said.

Lamia said that although many parents and counselors tell kids that bullies only pick on others because they were victims once themselves, bullies and victims have very different personalities. She said that when the confident pick on the sensitive, the sensitive victims do not suddenly become confident bullies.

Instead, Lamia said, people become bullies when they pick up shame on their own – a bully does not necessarily pass it to them.

“Let’s say your parents are both high-class alcoholics and you see your father passed out drunk every night, or your mother, and you feel ashamed,” she said. “Well that shame ends up feeling like it’s yours.”

There are four ways in which a person can respond to shame, according to Lamia. They can withdraw, avoid, attack themselves, or attack others. The bullies attack others. The victims either withdraw and avoid others or take the more dangerous route and attack themselves.

“Shame is such a poison-emotion because behind almost every suicide is shame. Behind most addictions is shame. In fact, behind most violence is shame,” Lamia said.

Lamia said that the scary part is that most high school students don’t even know when they are being offensive to others and passing out shame.

“They’re not even aware of their shame, that’s how well it’s hidden,” Lamia said.