Since its founding in Marin in the mid-1970s, mountain biking has been a controversial issue amongst the various groups that frequent the county’s vast public spaces. Despite its large popularity, there is controversy over whether bikers should have increased access to Marin’s trails.

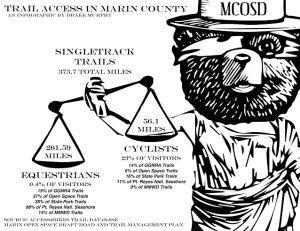

Cyclists have access to 26 percent of the 327 miles of trails on Marin Municipal Water District (MMWD) and Marin County Open Space District (MCOSD) lands combined.

According to a 2012-2013 survey conducted by the MMWD, cyclists make up an estimated 30 percent of visitors to Mt. Tam, the second largest user group. The trails that the county is most concerned about integrating with bikers are single track, which are approximately the width of a single bike.

The largest group of trail users are hikers, who account for about 70 percent of trail users. The other group of trail users are equestrians, who make up less than one percent of visitors to the mountain. According to Jack Gibson, the MMWD President of the Board of Directors, these two user groups are often against increased bicycle access because they believe that bicycles on singletrack trails could lead to dangerous encounters between the other two user groups.“They [equestrians] will resist, if a proposal went before the board today to increase the access to mountain bikers on the watershed; there’s no question there would be resistance,” Gibson said.

Gibson also mentioned that it is imperative to maintain compatibility between the various user groups, so that they can use the trail harmoniously and safely.

“We have to make sure that everybody is safe, and it’s not compatible to have hikers or even horses on a trail that also has mountain bikers just because of the danger involved. So, we segregate some of the trails,” Gibson said.

Gibson said that the mountain biking community is very active in volunteer trail maintenance and general trail upkeep, and that there is an established trail etiquette for when riding past other trail users on multi-use trails.

There is a hesitation to add more bike-friendly trails on public land partly because of erosion. Both horses and bikes can erode the trail, causing a bumpy, uneven terrain.

“We’re not really getting a big problem from 54 equestrians, as opposed to almost 4,000 cyclists. There are so many people mountain biking that it creates much more damage to the trail just by the sheer number of them [riding] out there,” said Gibson, citing a survey done by MMWD in 2012.

Some cyclists make efforts to be respectful to the trail and other trail users, partially to improve mountain biking’s image.

“The procedure that we’re taught is to get off your bike and communicate with [an equestrian] to make sure that they know you’re there in order to establish a good relationship,” said senior Daniel Bernstein, a member of the Redwood Mountain Biking team.

Some cyclists disagree with the litigations surrounding singletrack trails, and choose to go on singletrack trails that are prohibited to cyclists. This behavior can result in a citation if the cyclist in question is spotted by a ranger.

Enforcement of these policies can be difficult because once a rider is seen breaking the 15 miles per hour speed limit, or is seen on an illegal trail, they can travel far down the trail in a matter of seconds.

Gibson reported that the park rangers give between 50 and 75 citations for illegal bicycle use a year. He also said that most responsible cyclists do not go onto illegal trails, and fewer build them.

An anonymous junior, “Norman” has participated in illicit trail building and illegal trail riding in the past.

“You have to remember that the only reason you have bikers building these illegal trails is because there’s nowhere else for them to go, and you have flow trails [twisting, bumpy trails] being built by Tamarancho [a flow trail in Fairfax] but it really doesn’t serve a purpose, because there’s no challenge to it,” Norman said.

Andrew Galbraith is a member of the board of directors for Marin-based Access4Bikes, a political organization that advocates for the opening of trails.

He said, “[Marin] was the first place in the country where people really saw mountain bikes on trails. I think when that first started to happen longtime hikers and other trail users, equestrians, didn’t like it.”

In the past, it was the equestrians who were the outsiders on the mountain, with hikers lobbying against increased equestrian access due to hiker safety and environmental impacts, according to Gibson.

“Then with the increased advent of mountain bikers, it actually created more unity between equestrians and hikers to ward off the bicyclists, so it’s a weird phenomenon that I’ve seen happen over the last 20 years.” Gibson said.

“Hikers still make up the largest group and they have access to every trail, as hikers should,” Galbraith said. “Equestrians make up a tiny percentage of trail users and have access to more trails than mountain bikers.”

Part of the reason for lack of access is that cyclists may have the potential to cause trail erosion more than hikers and equestrians.

The bumps that mountain biking can create on trails were seen as harmful to the trail until studies done by Edith Cowan University proved water runoff was more environmentally damaging than mountain biking.

“I tell mountain biking leaders who I meet with periodically the very best thing they can do is volunteer, help on maintenance on the watershed as they already do, and they’re doing that side by side with equestrians and hikers,” Gibson said.

There is discussion in the mountain biking community of change in policy, and as the spring season begins to pick up, cyclists are increasingly advocating for greater access.

“I’m not advocating that every trail ever should be legal for a mountain biker, but the percentage of trails open to mountain biking is so incredibly small, it just seems that it’s left over from a policy that really should be revisited,” said Harrison Jantze, a junior on the mountain biking team.

Offering a potential solution to the decades old problem, Jack Gibson has considered a plan to open more trails to bikes. He has mulled over the idea of a license individuals could acquire to take their bike on singletrack trails. Cyclists would renew it like a driver’s license, and they would have a wearable identification number that park rangers and the other user groups could identify them with.

Gibson isn’t sure this will be a legitimate option in the near future, but is hopeful that a coalition between mountain bikers and equestrians and hikers can form so that resistance to increased bicycle access is diminished.

To learn more about trail access in Marin, readers can visit Access4Bikes.com, where there are petitions to sign and facts to find, or visit the Marin Municipal Water Board website to find out more about the legal places to ride your bike, marinwater.org.