Silhouetted against the sweeping landscapes of the Bay and the Marin Headlands, the Bay Area is well known for its position in the counterculture movement of the 1960s and 70s. Political movements advocating for Black liberation and gay rights flourished amid the environment of leftist politics and free-thinking youth culture. Yet with this wave of new ideologies came a new form of social systems: cults. Groups such as Synanon and Peoples Temple in the Bay Area were originally formed with pure intentions of helping local communities. However, these groups soon devolved into cults and greatly shaped the lives of many local residents.

While these cults have gained an infamous reputation today, the abuses within them at the time were often kept hidden from the public eye. Dewey Livingston, local historian and Redwood graduate of the class of 1971, spoke to his observations of cult members as he was growing up in Marin.

“We would see groups of people with shaved heads coming into the store [or] driving around in trucks and it was curious…In the community, we didn’t see a lot except for the shaved-headed people,” Livingston said. “We knew that there was this big drug treatment center and that it was quite successful. [The Synanon members] showed up at times in the local Western weekend parade, [but] it was strange. The average Marin resident didn’t know what was going on there.”

The Bay Area served as a ground zero for much of the political activism of the counterculture movement, as many Americans sought out different ways of thinking and living. For many, they found that in cults, as psychology teacher Jonathan Hirsch explains.

“California in the 1960s and 1970s was a place where there were a lot of opportunities to settle physically, but also ideologically. California attracted a lot of people who didn’t feel like they fit,” Hirsch said. “The cliché is the hippie movement, the free love movement of the 1960s. But that was a magnet for a lot of people: the idea of a new way of living.”

These conditions led to the rise of the Peoples Temple, a church and social organization in San Francisco that was founded by Jim Jones and which is known today as one of history’s most infamous cults. However, the Peoples Temple’s beginnings were a far cry from the eventual violence for which the cult would eventually be known, as local historian and founder of the historical documentation website foundsf.org, Chris Carlson, explained.

“There’s a sense of a loving community that [the Peoples Temple provided]. [Members] were invited into something that offered them a human community, a family and the ability to have their physical needs, like food or shelter, taken care of,” Carlson said.

As Jones gained more influence, specifically through his position as religious leader, he became the central figure of the cult, Hirsch explained.

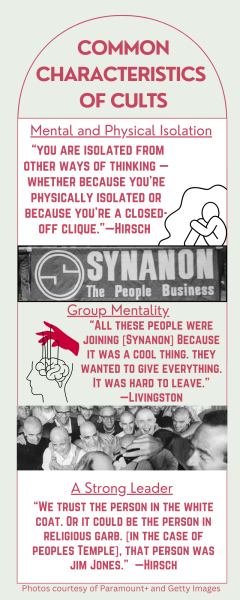

“[The Peoples Temple] was [initially] a very liberal — bordering on radical — church in San Francisco. But over time, it drifted. Part of that [shift] is that idea of the cult leader, which in psychology, we call the lab coat effect— we trust the person in the white coat or the person in religious garb. [In this case], that person was Jim Jones,” Hirsch said.

However, as Hirsch described, cults such as Peoples Temple and their leaders do not necessarily begin with the principles of eventually becoming a cult.

“Most leaders don’t necessarily set out [with the goals of], “I’m gonna get them.” Even people like Jones didn’t have a vision for how it was all going to end when he started the People’s Temple,” Hirsch said.

Over time, the Peoples Temple’s initial goals became corrupted, and the cult grew increasingly isolated from the rest of society. Eventually, that led to its transformation into a cult, as Hirsch described.

“When you are united by anything and you are simultaneously isolated from other ways of thinking—whether it’s because you’re physically isolated or it’s because you’re just a closed-off clique—you get something called group polarization. [This is when] a group tends to unite against the outside,” Hirsch said. “They start to think, ‘Oh, no one gets what we’re about. No one else would understand. So all we’ve got is each other.’”

Ultimately, the rising tensions in the Peoples Temple, and the increasing volatility of leader Jim Jones, culminated in the massacre on June 28, 1978, in Guyana, when 909 people died after drinking cyanide-laced juice at the hands of Jones. According to Carlson, however, this moment is often misrepresented in popular culture.

“‘We drank the Kool-Aid’ is a common expression these days. But the implication is that those people willingly followed a cult to their death. And that’s a misreading of what happened. People were forced to drink it. They knew what was happening and they did not want to do it,” Carlson said. “They were forced at gunpoint; [the juice] was administered into small children with syringes, forcing their mouths open and squirting it into their mouths. It was a hideous mass murder… The people there were pretty clear. They didn’t want to die.”

Livingston reflected on the impact that witnessing those cults in real time had on him and the local community.

“Hearing about the Peoples Temple and watching that unfold in the news was really moving. It was very surprising that it could go to the extent of all of these people dying by the orders of one guy. It makes you think about the state of the world,” Livingston said.

Yet the impact of the cults in the Bay Area was not isolated to just Peoples Temple, spreading across the Golden Gate Bridge to Marin County. The cult of Synanon, located in Tomales Bay, relied on similar tactics — such as isolation and a strong leader — to consolidate power. Like the original positive intentions of Peoples Temple, Synanon was founded with the goal of rehabilitation for those suffering from alcoholism. Livingston spoke to the rise of Synanon and its position in the local community.

“In a nutshell, Synanon came out of a program that a guy named Charles Diederitch started in the 50s. He had come up with some pretty good techniques for treating drug addiction and alcoholism in Los Angeles,” Livingston said. “Pretty soon, he got good publicity around the nation, for what he called Synanon and the Synanon Game, which was a technique for breaking down your personality as a way of being able to withdraw from these addictions. It turned into a real community… By the mid 60s, it was a legitimate group.”

Livingston discussed how the Synanon Game allowed the leaders of the cult to gain significant control over members’ psyches, through confrontational group dynamics.

“The Game was like group therapy, where a circle of people would be in there and just let everything out. Often, that was anger. They would insult each other, and if you were the subject for the moment, people would just be yelling at you what a piece of crap you were and how ugly you were,” Livingston said.

Oftentimes, as fringe groups such as Synanon develop, they begin to separate more and more from the rest of society. Livingston described how the vital shift from community to cult occurred in Synanon.

“One change that happened was that rather than joining [Synanon] for treatment for drug addiction and alcoholism, people became attracted to it for its lifestyle. These happy people [were] living in these beautiful ranches with a benevolent leader, who did personal work on themselves, and worked in the garden and the roads: a utopian community was how people saw it,” Livingston said. “All these people were joining because it was a cool thing. They wanted to be a part of it and they wanted to give everything to the group. It was hard to leave.”

Synanon’s corruption and abuse not only affected cult members, but the surrounding Marin community as well. The violence within Synanon’s walls soon seeped into the community as Dewey detailed a local’s involvement in Synanon members’ escape.

“There was a nearby rancher named Alvin Gamba Nene. Kids and sometimes adults would show up at his door in the middle of the night, and he would [help them]. It became a bit of an underground railroad type of situation. One night, a group of shaved-headed people surrounded [his] car and dragged him out and beat him,” Livingston said.

Additionally, the Tomales Bay newspaper The Point Reyes Light played an instrumental role in exposing the reality of the cult’s activities and received a Pulitzer Prize for their efforts. Tess Elliot, editor for the Light, described her knowledge of the newspaper’s role in breaking down Synanon.

“Kathy and Dave Mitchell, [who ran the newspaper], were doing a lot of the reporting themselves and so there were many stories over a couple of years. That Pulitzer was for not just a single article, but all the coverage that took place over a long period of time,” Elliot said. “Dave Mitchell was put up to the task of being the one to [reveal the reality of] Synanon because the other larger papers were too afraid or they felt legally vulnerable.”

Whether drawn in by the psychological component of a strong leader, by political messaging or by a sense of need for belonging and community, it is important to take into account the variety of reasons for which people may become involved with cults, and how not all experiences with cults look the same. Livingston spoke to the diversity of those who joined Synanon.

“A lot of [the Synanon members] were really intelligent. They were college professors and family people. Whole families would join. They weren’t automatons who were looking for a cult. They were people looking for a good life in a different way,” Livingston said.

Likewise, Livingston reflects upon the susceptibility of people to joining cults, a trend which extends to the current day.

“These days, we’re so far removed from our tribes where everybody was taken care of and [from a] communal existence. We’re so fragmented these days that people are looking for experiences like that, and then [it is a matter of] how susceptible they’ll get to the influences of other people,” Livingston said.

Similarly, for Elliot, her experience with a Buddhist group in college had influences of a cult-like mentality. That time in her life shaped how she views those involved with cults — with empathy, and with understanding of the difficulty of such situations.

“I was very involved in this group. After I was [hurt by my involvement], I really have some appreciation for what it’s like to be in a group like this,” Elliot said. “You believe what you’re doing [is] something special and something different. It’s very easy to want to let somebody tell you how things are or [how] to live your life in a way that is more meaningful or more effective.”