Art repatriation

Returning works to their origins

December 14, 2022

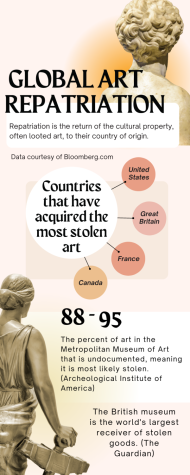

Long, draping stone cloths and wide soaring wings contrast a long empty hallway; the Winged Nike of Samothrace — a Greek statue — stands alone, stripped from the island of Samothrace thousands of centuries ago. Winged Nike, among other stolen pieces, has been at the forefront of a recent controversy: artwork repatriation. Referring to the return of stolen cultural art to their countries of origin, repatriation is a topic that impacts different cultures around the world. For thousands of years, people have expressed their spirituality and cultural beliefs through the creation of art. In the dawn of imperialism, powerful nations longed to expand their influence and resources, conquering various cultures, as well as their treasured art.

Through imperialism and colonialism — motivated by the spread of various religions and political beliefs — nations across the globe were reshaped. Substantial aspects of cultures were stripped, including art. From European explorers deconstructing the Parthenon in Athens to Adolf Hitler scheming to steal “degenerate” art, the practice of removing art is heavily tied to the entirety of world history.

It was not until the 1950s when the stark truths of colonization and war crimes began to be exposed and a broad desire for restitution emerged. Twenty years after the fact, a collective effort was put in place to repatriate. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization convention created a permanent intergovernmental committee that facilitates the return of stolen art and cultural property. These attempts at repatriation have largely been directed at the British Museum and other popular art institutions because they derive the most profit from keeping stolen art. Artworks like the Benin Bronzes, which were looted from Nigeria by British soldiers in 1897, are spread across several prominent museums and have been called for return.

However, these incidents are not isolated internationally since they occur in the United States as well. During the boom of archaeological science in the 1800s, thousands of unknown indigenous graves were excavated. Ancestral remains and art stolen from these graves majorly reside in museums, which Indigenous Americans took a stand against. In 1990, Congress responded with the passing of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), returning more than 1.7 million grave goods and sacred objects to their original homes.

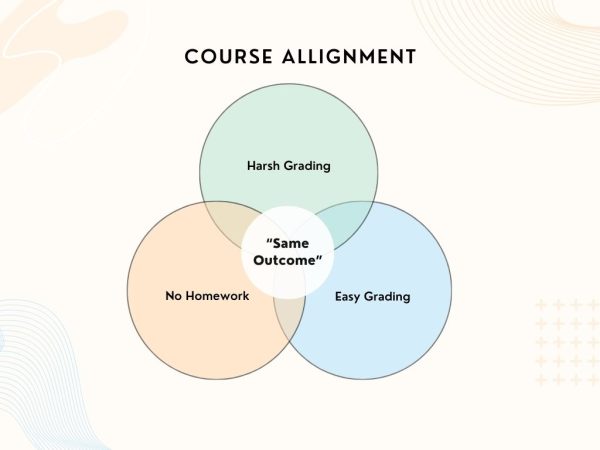

Some argue this legislation is not enough. Joely Proudfit, director of the California Indian Culture at California State University San Marcos, spoke to the San Diego Union-Tribune regarding the faults of NAGPRA. There was an error loading the selected infographic

“Unfortunately, loopholes have been used for many years to slow down the return of materials or to try to rationalize maintaining those materials by splitting hairs over what is defined as ‘human remains’ and ‘funerary objects.’ NAGPRA is a good start, but it doesn’t go far enough, because all cultural items should be returned to tribal communities. If the tribe wants it back, they should have it back,” Proudfit said.

Jackie Swift, the repatriation manager for the National Museum of the American Indian, claims these artifacts should only reside in their origin country.

Because of our policy and principle, there should be no [cultural objects] under our stewardship; they should all be returned to their original place. We don’t use the term ‘art’ [when discussing the return of stolen objects] because they were never supposed to be art, they were supposed to be with the native people for their burial sight and afterlife. No one gave consent for them to be taken. — Jackie Swift

Expressing historical hardships across different cultures, art creates a means to remember and learn from the past. Lauren Bartone, an Advanced Placement Art History (APAH) teacher, notes that it is easy to see art as something of the past.

“It’s easy to forget that everything in a museum got there somehow — it wasn’t born there. Museums were built by countries to protect a certain kind of identity or build a certain kind of history, and that history is always constructed. It doesn’t just happen,” Bartone said. “The role of art in these institutions has a complicated history, and for a long time, we’ve ignored it. In the past 10 years, there have been significant worldwide efforts to rethink colonialism and look at the broader impacts of colonialism on art.”

Many believe that cultural objects belong to those that created them, as they are a crucial part of national identity. Meanwhile, others are against repatriation, arguing that the origin countries do not have adequate facilities to house art pieces. This could be from poverty or armed conflict, which makes it hard to receive repatriated materials. Additionally, they argue that these universal museums enable a variety of art to be seen by large sums of people. With no clear legislation, art enthusiasts and curators are left to argue among themselves.

Senior and APAH student Avery McGovern claims art stripped from its original home would be a “nightmare” to see in museums.

“Taking a walk through the British museum would be a reminder of the violence and oppression that so many cultures had to endure as a result of colonialism. It should be no secret that artwork played a huge part in Europe’s dark history and [in order] for us to start anew, we should be returning all of these artworks,” McGovern said.