Concrete history hidden among the headlands

June 8, 2022

Well-known for its natural beauty, the Marin Headlands is a popular place for both outdoorsmen and residents. Located just outside of San Francisco, the headlands contain beautiful beaches, miles of hiking trails, quiet forests and gorgeous views of the Golden Gate Bridge. However, behind the beauty lies remnants of the military power the headlands once held. Scattered among the rolling hills of the headlands are concrete bunkers that protected the San Francisco Bay from attacks during the World Wars.

Since 1853, San Francisco has been defended by Fort Point, a former military base located on the northern tip of San Francisco. Marin’s modern military history began when construction of the defenses continued into the headlands in 1899, with the establishment of Battery Kirby and Battery Mendell. The batteries, or small military outposts containing artillery, were used as defensive measures to combat world tensions in the prelude to World War I.

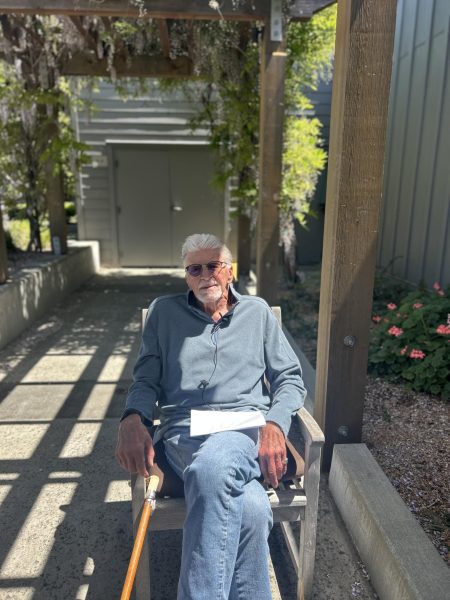

Marin’s militarized past has fascinated many people, including author Matthew Kent, a San Francisco resident, who has dedicated much of his life to studying and documenting the batteries ever since he first explored them with his father as a child. Kent wrote “The Harbor Defenses of San Francisco,” along with many other books and articles, on the defenses that were built to protect the bay.

“[Building defenses in the Bay Area] started with Fort Point [in 1853,] Kent said. “After the civil war, there was the first introduction of concrete in the early 1890s. The San Francisco side and Marin side in the 1890s were [on] the original gun line, [but] San Francisco was the original line of defense.”

A gun line is artillery arranged in a tactical firing position, and the Bay Area’s gun line served to protect the heavy industry, most notably ship building, in its boundaries. The fortifications located across San Francisco and Marin protected the Bay Area from all angles, making any attack on the industry within it difficult.

Although they were primed and ready, not a single round was fired at enemy ships from the bunkers. No enemy ship challenged the safety of the Bay Area, and the bunkers lay dormant for many years.

During World War II, the San Francisco Bay was threatened again, and Fort Cronkhite and its batteries, complete with new 16-inch guns, were built among the hills.

Most of the batteries featured multiple gun mounts, capable of sending artillery miles into the Pacific Ocean. According to the Harbor Defenses of San Francisco, on July 1, 1940, a 16-inch test round was fired from Battery Townsley, located near Fort Cronkhite. The test aimed to assess the range of the guns and the ability of the military officers to fire the guns. Although it was expected to fall short of the Farallon Islands, the bullet sailed over them and crashed into the ocean, miles past the islands, traveling 30 miles in total.

Although the site’s defenses performed exceptionally well, according to the Coastal Defense Journal, the new technologies and lack of use led the U.S. military to abandon the sites, turning them over to the U.S. National Park service in 1972. Ever since this transition, civilians have used the bases to leave their artistic mark on the land.

These civilians have led Marin Headlands to become a graffiti hotspot in recent years, incentivized by the lack of police presence. Marin treats graffiti as a crime, forcing some artists to pay fines, serve jail time and possibly face felony charges in accordance with California Penal Code 594 PC. However, the spacious and secluded headlands provide freedom from the repercussions graffiti artists face in other parts of Marin. Unlike most of Marin, the headlands are non-residential, which reduces the need for police and allows taggers to use the land without the threat of legal consequences. The headland’s law enforcement comes in the form of Park Rangers rather than police officers. Artists such as KOBA, who asked to be referred to by his tag, are able to take advantage of the freedom granted by the headlands to practice their art.

“Graffiti is a nuisance in most of Marin, but people just care less [in the headlands]. It’s almost become a feature of the bunkers here — kind of a beacon of personal history as well as buildings that tell a larger story,” KOBA said. “[The bunkers] give [artists] an opportunity to really put time into a piece [of art] and not worry about [police].”

Artists like KOBA have seen a large shift as graffiti has become viewed as art more often recently. The famous street artist Banksy, sold the painting “Love is in the Bin” for $25.4 million at the Sotheby’s auction in 2021, showing its more mainstream appeal. However, even as some Graffiti artists become mainstream, not everyone is accepting of graffiti. Generally, it is not considered art, even within the graffiti community. Some writers prefer investigating the thrill of committing a crime and avoid thinking of themselves as artists.

“I really think [graffiti is] an art form, but I know not all the writers think that. Some think graffiti is vandalism and enjoy the criminal aspect. I don’t understand that,” KOBA said.

In Kent’s experience of exploring and writing about the headlands for many years, he has seen an abundance of graffiti. Yet, his knowledge has not convinced him that graffiti adds to the scenery.

“As somebody who grew up in San Francisco and did graffiti in high school, I have an appreciation for it,” Kent said. “But, I didn’t go around and ruin stuff visually or impede on someone’s view, and that’s what [the taggers are] doing to these structures. They are ruining the whole thing essentially. I think there is no place for it.”

Like Kent, some local residents who enjoy the headlands’ history and landscape do not appreciate the graffiti aspect of the modern location. Justin Brown is one of these local residents and has been biking in the headlands for years allowing him to observe graffiti throughout the area.

“I think [graffiti] definitely takes away from the buildings and the beauty of the headlands. I guess it is a new form of art, but it’s not something that I enjoy seeing,” Brown said.

Despite the headlands’ defensive importance in the 20th century, they have slowly been falling into disrepair. The National Park Service is not restoring many of the historical buildings due to funding constraints and has a policy of leaving landmarks under their supervision as they are rather than making changes to improve the structures. This is visible around Battery Townsley, where many of the former military structures are slowly falling into the ocean and “warning, unstable landscape” signs litter the hiking trails.

“The policy is that these structures are rotting in place, and probably in 100 years, if [they are] not maintained or if [they haven’t] succumbed to the elements by a landslide, a lot of [these buildings] will be lost,” Kent said.

As the headlands continue to age, future generations will have less and less access to the history residing in the bunkers. In other locations, such as San Francisco’s Fort Point, history has been preserved and restored by the National Park Service, however, no plan to protect the headlands has been initiated. Conserving the headlands requires Marin residents to express their appreciation of the history to the National Parks Service by advocating for their preservation.