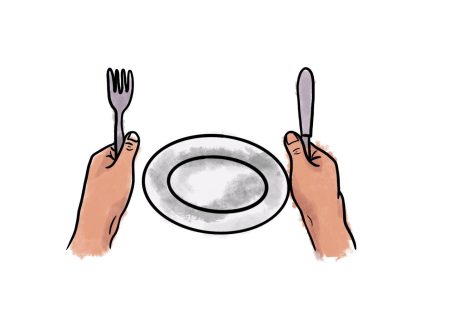

Marin County is home to hundreds of food insecure individuals and families under a facade of wealth

May 19, 2022

Bags full of potatoes, yams, celery, bread, yogurt and milk make their way into the hands of hundreds of people, hoping that they will have enough food to feed themselves and their families for the week. Receiving weekly groceries from the Canal in San Rafael, Marin residents are temporarily relieved from the burden of food insecurity. Over the past three years, food insecurity rates have soared globally, having been worsened by the pandemic, during which world hunger rates rose by 18 percent.

This issue of hunger worldwide can be singled down to our very own Marin County. Marin is home to more than 48,000 people who worry about where their next meal will come from. CalFresh, California’s state Supplemental Nutrition Program, estimates one in five people in Marin face food insecurity – including 11,753 children. Many of these young adults facing hunger are within the Redwood community.

With the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine, who are two of the world’s largest food producers, millions more are expected to face food insecurity this year. A United Nations statement from March estimated that the impact of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine on the global food market could potentially cause an additional 7.6 to 13.1 million people to go hungry.

David M. Beasley, the executive director at the World Food Program, a United Nations agency responsible for feeding 125 million people per day, recognizes that the Russian invasion of Ukraine is fueling the global hunger crisis.

“Ukraine has only compounded a catastrophe on top of a catastrophe. There is no precedent even close to this since World War II,” Beasley said. “The United States has already experienced a rise in grocery prices with an increase of 8.6 percent in February, making it the largest inflation of food prices in the last 40 years. The war will only cause those prices to rise even more, which endangers those already living on the verge of food insecurity.”

Marin is no stranger to fancy restaurants and high end stores. And although it is true that Marin is a wealthy community, with the average annual income at $110,843 compared to the United States average annual income of $65,712, 7.23 percent of the population lives in poverty. Thus, deeming Marin as an affluent place does not fully encompass the socio-economic variety of neighborhoods and families that call Marin their home. Because of the facade of wealth that Marin obtains, people often overlook the struggles that some community members face. Michael Watenpaugh, superintendent of San Rafael City Schools, puts it perfectly: “The first impression is that Marin is a wealthy community,” Watenpaugh said. “But if you dig in, you find a significant population of poor families here. And there is a very big need to address them.”

Research suggests that hunger also influences students’ performance in school. Roaring stomachs can cause students to be distracted, hyperactive and aggressive. These behavioral issues can lead to developmental delays and disabilities. Research from Feeding America, a nationwide network of more than 200 food banks, demonstrates that children from families who worry about where their next meal will come from are more likely to score lower on tests or even repeat a grade level.

Lisa Herberg, the Tamalpais District Student Nutrition Director, dissected the impact of adequate amounts of food on a student’s learning experience.

“Generally, when you have less money for food, whatever you can afford has poor nutrition. Especially among younger children, they don’t have the proper nutrients to support their developing brain. It affects their cognitive ability for learning. They have less energy and less focus in the classroom and in school,” Herberg said.

Herberg estimates that anywhere from 80 to 100 students receive free breakfast from the CEA and around 450 to 500 students get their lunches from there as well.

“We were at 600 [students] earlier on in the pandemic but it has eased up. Prior to the pandemic, six percent of our students qualified for low income, so we are assuming we are about the same because we don’t collect applications,” Herberg said.

Following the shutdown at the beginning of the pandemic, many people’s jobs were jeopardized, affecting their ability to afford food. Herberg volunteered at pop up food banks during the height of COVID-19 and witnessed Marin’s food insecurity issue.

“Specifically, what I saw when I was volunteering at the food bank was families with little children and seniors. A lot of the seniors are on a fixed income who have social security

and possibly not pension,” Herberg said. “For families that have young children, childcare is expensive and it takes away from the food that you can put on the table. If you can’t work because you have more children then it would cost to pay for childcare, then you don’t have that job to pay for food.”

and possibly not pension,” Herberg said. “For families that have young children, childcare is expensive and it takes away from the food that you can put on the table. If you can’t work because you have more children then it would cost to pay for childcare, then you don’t have that job to pay for food.”

There are many Redwood students who have been inspired by the distress of COVID-19 and recent worldwide conflicts to take action against local hunger hardships. Sophomores Olivia Villanova, who organized a canned food drive last year, and Lauren Ball, frequent volunteer at Marin Food Bank, both stress the importance of community members joining them in mitigating the effects of hunger in Marin.

“When you get the opportunity to be face-to-face with people you are helping and see them smile, it makes supporting your community feel so much more real,” Ball said.

Villanova organized a canned food drive at Redwood last year after being inspired by visiting the Tenderloin district in San Francisco. Villanova was able to schedule the food drive through St.Vincent DePaul in Novato, a non profit organization working to combat hunger. While arranging this event, Villanova reflected on her gratitude towards having a stable supply of food at home.

“Some people don’t [know] when their next meal is going to be or what it is going to be. I’m lucky enough to know I’m going to go home to a house full of food at night,” Villanova said.

Villanova believes the stigma surrounding food insecurity in Marin makes the issue not only more difficult to talk about, but also makes it harder for people facing food insecurity to reach out for help.

“Most people view Marin as a wealthy place so the idea that some people in Marin are facing hunger daily doesn’t cross our minds often. We need to make it a more normalized issue,” Villanova said. “Even though we live in a wealthy community, there are still people struggling who need help.”

This sentiment is shared with junior Jack Callaghan who has discovered the importance of citizens’ involvement in the community through his volunteer work at the Canal Food Distribution Center. Callaghan helps at the Canal Distribution Center every other week where he sets up food stations passing out food to residents in need.

He also noticed the lack of discussion surrounding hunger in Marin.

“For a lot of families here, it is a given that food is on the table. To have to bring up the conversation where it is not can be very difficult for some people,” Callaghan said.

Following Callaghan’s work at the center to fulfill volunteer requirements during his freshman year, he continued to come back. Callaghan’s experiences exhibit how students can use their actions by taking initiative in order to make a difference.

Villanova expresses how many students have created a sense of shame around eating food from the Covered Eating Area (CEA).

“A lot of people complain about the CEA food, but for some kids that food is all they eat,” Villanova said.

Herberg also highlights the importance of not alienating the students who eat from the CEA. Throughout her 30 plus years in the school nutrition industry, in which she has worked with grades K-12, Herberg recognizes that there is never a stigma around receiving free meals among elementary school students. However, once students reach middle and high school age, this mindset changes.

“In middle school and high school, the students who qualify for free meals won’t come to eat. They will choose to go hungry because of the stigma. They will wait until they get home. What has changed [with free meals] is that it has reduced the shame around receiving school lunches,” Herberg said. “Just today, I saw students coming out of the CEA with food and smiles on their faces. It doesn’t matter how much money you make, it is just okay to come and eat.”