Breaking the silence: Putting an end to sexual assault in Marin

December 13, 2021

For decades, Marin County has been considered one of the most desirable places to live in the U.S. Surrounded by mountainous landscapes and redwood trees, the county is seen by many as a perfect bubble, shielded from the real world. However, while Marin may have its luxuries drawing people to live here, the county is not as sheltered from harm as many believe. Sexual assault is a serious issue that is prevalent in the San Francisco suburb.

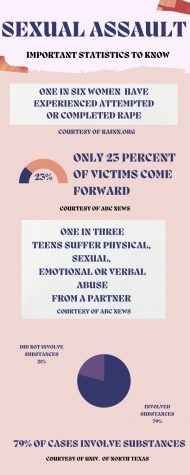

For years, hundreds of sexual assault cases have been reported in the county, with 522 cases per 100,000 people in 2011. In comparison, in 2020, the national rate of rapes per 100,000 people was 38.4. In response to these high rates in Marin, many people across the area have taken a stance against sexual assault and are outraged that high school administrators seem to take little action to mitigate the issue.

One Marin activist, 2021 Archie Williams High School graduate Annabel Smith, has spent the past few years bringing awareness to the issue in her community. According to Smith, despite the many sexual assault cases in Marin, there is not always acknowledgment of the subject.

“I think [sexual assault] is being swept under the rug because despite how liberal Marin County is — it is still like every other place in the world: male-dominated,” Smith said.

Smith took a stand on Sept. 22, 2021, when she posted a list of teenagers, including several Redwood students, she claimed to be sexual predators in Marin. Smith then encouraged followers to send in names they claimed to be predators. Although no one on this list has been legally convicted, according to Smith, all accusations are public and she was meticulous about which names were posted. She believed the most efficient way to inform her peers about this pressing issue was by making this post on her Instagram story.

Smith has seen how sexual abuse has destroyed the lives of many of her close friends, sending them into bouts of depression and other mental health issues. This topic reaches an even more personal level to Smith, as she herself is a victim of sexual assault being raped in eighth grade. Since then, she has dedicated her time to addressing sexual assault by partaking in clubs that are aimed to help victims, both in and outside of school. Smith and her friends’ experiences have urged her to spread more awareness about the issue.

One main problem Smith has identified is that many young women experience rape and or sexual assault, not realizing it has happened until months after the fact, something Smith experienced herself. She believes this adds a layer of complexity to dealing with sexual assault because it takes away any sort of timeliness to deal with a case of assault. According to a research review of over 28 studies by The Sage Journals, 60.4 percent of women who experienced sexual assault did not initially recognize their experience as rape, despite their account fitting the exact definition. The reason many victims do not recognize what happened to them may be due to how unsettling and traumatic the situation was. According to the Canada Department of Justice, trauma can affect and impair the processing of memories.

“I was raped, and I didn’t understand what [had] happened until late my sophomore year. I always had this pent-up trauma since eighth grade, and I never knew for the longest time why I was so scared to be touched by someone or to talk to any boys,” Smith said.

Her own experiences motivated her to make these posts, in which she hoped to spread more awareness. Gaining over 8,000 views and more than 250 responses on the post, this goal was accomplished. Her post sparked discussion and drew attention from all around Marin County.

Charlotte Rudolph was among over 100 teenagers in Marin who came forward and named a predator to Smith after viewing her post. Rudolph believes that the secrecy around the issue of sexual assault in Marin is in part due to the immense wealth in the area.

“Money definitely [causes silence],” Rudolph said. “The more money you have, the more power you have. A lot of people are afraid to go to court because their family [might not be] as wealthy as other families in Marin and they know they don’t have the lawyers and they will lose.”

The lack of access to lawyers is only one part of the economic disparities that allow for abuse to go underreported. The financial burden placed on the victims is staggering. According to a 2014 report from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the estimated lifetime cost of rape is $122,461 per victim. This estimate included medical costs, lost work productivity among victims and victim property loss or damage.

Smith has her own beliefs as to why this sexual assault in Marin persists, but some students have another theory: the lack of relevant and useful consent education at schools in Marin County.

A junior at Marin Catholic High School, referred to as “Sarah” for anonymity, experienced sexual assault. To help address situations like hers and Smith’s, Sarah says that school presentations need to be modified. To her, they are not effective as they fail to discuss real-life situations, leading students to only hear of exaggerated versions of sexual assault.

“Guys need to hear scenarios that are actually happening. I feel like a lot of the time, [men think] sexual assault is when a girl is kidnapped and her head is banged against the wall, but that’s not the majority of these cases,” Sarah said.

In reality, according to the British Broadcasting Center, more than 90 percent of rape and sexual assault victims knew their attacker before the incident occurred, which Sarah claims is vital information for teens to know. She also mentions the importance of recognizing the threat of sexual assault in a party situation.

Roughly half of the sexual assaults committed on college campuses involve situations in which the perpetrator, the victim or both had consumed alcohol. Additionally, according to the Maryland Collaborative newspaper, victims sexually assaulted after drinking report higher levels of self-blame and often fear that others will not believe them or that they will be blamed for the assault.

“It’s really important for [teen boys] to hear, ‘When you’re at a party and a girl is over-drinking, that’s not your cue to make a move at all,’” Sarah said.

The unsettling number of current Redwood students who were on Smith’s list caused a surge of confusion and discussion amongst the Redwood community. The Wellness Center recognizes the prevalence of sexual assault at school and its lingering effects. They are aiming to improve education and awareness by working with Peer Resource, a student leadership class designated to educate students about mental and sexual health. The Wellness Center also has a new curriculum they present to freshman Social Issues classes called affirmative consent. It explains that unless a partner explicitly says “yes,” you do not have their consent. Wellness coordinator for the Tam Union High School District (TUHSD) Jessica Colvin believes that adding affirmative consent to the curriculum is a positive change.

“For a lot of young people, these are some of their first sexual experiences, and I want them to be safe and neutral. I want everyone to feel like they have a voice and that they’re being asked if they’re comfortable and if this is what they want to be doing, instead of [having partners] making assumptions about what they think someone wants,” Colvin said. “Everyone has the right to decide what another person can do or say [with] their body, and they can change their mind at any time.”

However, there is still a lack of accurate depictions and education about consent within school programs. Senior Molly Pitts, a second-year Peer Resource student, expresses that the services available at Redwood still need improvements.

“I’m confident in saying that everyone has room to grow and learn how to better support each other. I don’t think [sexual assault] is a topic that’s going to be fixed overnight. That’s for sure. Taking little steps is how we’re going to cover ground on this together,” Pitts said.

Pitts claims that despite this conversation being a tough one to have, it is necessary — which was exactly what Smith aimed to do. When she posted the names of accused perpetrators, she wanted to destigmatize the conversation of sexual assault and to allow victims to feel safer about coming forward. Smith hopes to end the overwhelming backlash and questions victims often face including many of the victims who came forward on the Instagram posts. Although victims were kept anonymous, Smith recalled that multiple girls who had contributed to the names of the perpetrators on the post had people swarming them and bartering them with questions, asking, “What really happened?”

Bringing up a victim’s trauma can be incredibly triggering, especially if this trauma is being invalidated. Senior Jenna Benyon has witnessed those close to her experience sexual assault, and since then has educated herself on the issue. She describes the situation Smith references as “mob mentality,” where a victim comes out with an allegation, and many people will bring up the victim’s trauma to test the “truthfulness” of the accusations.

“[The mob mentality] makes girls at Redwood especially afraid to stand up for what’s [right] because so many people allow [this mob] to happen and think it’s normal,” Benyon said.

According to Smith, factors such as “mob mentality” have allowed sexual assault to persist for far too long. Additionally, according to TUHSD superintendent Tara Taupier, under the Trump administration, national changes to Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972, which prohibits sex-based discrimination in educational programs, might further discourage victims from coming forward. Those accused of sexual assault must now provide the administration with the name of the accuser and submit to questioning about that person in an investigation.

“A lot of victims don’t want to necessarily go through that kind of process. It feels very invasive to many people. I think the changes could have a chilling effect on people reporting. [Sexual assault] is a really difficult thing to report. That kind of exposure can feel really out of your control during a time when feeling in control is very important,” Taupier said.

A Title IX confidential reporting form affiliated with the TUHSD district is available, but according to Taupier, not everyone might be aware of it. Additionally, under Title IX, reports must be filed within six months of the date of the incident or the date that the victim learned of the incident. Taupier believes six months is too short a time frame.

“I think everyone processes trauma differently, and for some people, it takes them longer to talk to anybody about it or to process it themselves in a way that they feel like they can actually tell us about,” Taupier said.

Although the superintendent has the power to grant extensions, and the administration has never refused to investigate a report, Taupier worries that the official short time frame could still discourage people from coming forward.

To overcome these barriers, the action Benyon and other students encourage is to hold our peers accountable. Students like Pitts and Benyon claim that if the administration is not doing all they can to help victims, students must speak up and seek a solution themselves.

If you or someone you know is or has been a victim of sexual assault, the Sexual Assault Hotline is available at 1-800-656-4673 and the confidential reporting form is available at https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSeC4wbU19iadyFYS5__h40V6_lHmIiPi0ZmrEFVtQETsTG5Jw/viewform.