Restorative justice: Peer Solutions combats the school-to-prison pipeline

One dreary morning in 2005, a Black seventh-grade student at Mill Valley Middle School brought his grandfather’s Swiss Army knife to school. Delighted with this relic of the past, the student excitedly showed the knife to his friends. By the end of that day, the school administration had been notified, and in the age of zero-tolerance policies, the student was expelled. The student was eventually sent to Marin’s Community School, a school for middle and high school students who had been expelled or were on active probation. Although this student had never come into contact with any drugs before attending Marin’s Community School, within three weeks of his enrollment he was being used as a drug mule, carrying drugs for high school gang members.

This student is one of many who have been failed by the Marin County justice system, school disciplinary systems and juvenile detention programs in California. These cases are not as uncommon as they may seem, and they are disproportionately prominent amongst students of color, primarily those who are Black or Latinx, according to Don Carney, the executive director of Youth Transforming Justice (YTJ). YTJ is an organization dedicated to providing alternatives to suspension, eradicating discrimination in schools and teaching drug and alcohol harm-reduction methods to the Marin community. The failed diversion of systemic juvenile delinquency inspired Carney to teach and practice restorative care in the Peer Solutions program in YTJ.

“These children are traumatized by poverty and race, and that intergenerational trauma fills the school-to-prison pipeline, and then it fills the prisons,” Carney said.

Carney began his career in restorative justice and active service in 1975 by creating and running a group home for wards of the state, children whom the state has decided no longer belong to their parents and are put up for adoption or put into foster care. While living with the kids in the home for 10 years, Carney used restorative practices to help address and heal the children’s trauma, often stemming from unstable home environments. He teaches these same techniques to Peer Solutions, a group of young Marin students, formerly known as Youth Court, to help end the school-to-prison pipeline and generational trauma in Marin.

In YTJ meetings, which are currently on Zoom, they start with Carney giving an overview of the importance of working with young people to make sure they learn from their mistakes and do not repeat the same harmful behavior. He discusses class, race and substance abuse, outlining the potential factors that may have brought the young person to the meeting. Carney and the facilitators repeat that the respondent has taken accountability for their actions already, and if they successfully complete their restorative plan, they will have no criminal record and will be excused from probation. Then, the Peer Team and observers take an oath of confidentiality, swearing not to repeat anything they will hear, and the case begins.

Each member of the Peer Team questions the person about their life circumstances. Many of the Peer Team members have been in the position of the person being questioned, so there is a level of connection and understanding in the meeting that is authentic and real. In the meeting, the Peer Team deliberates a restorative plan and presents it to the individual. The plan typically consists of community service hours and serving in the Peer Team, but may include recommendations for counseling, tutoring or addiction support.

These restorative practices that the Peer Solutions team use have created a positive impact on the young people they serve.

“I’ll have kids come to the [YTJ meetings] scared. They’ll go home, and [their] mother will call me and say, ‘My kid was scared to death to go to [Peer Solutions], but came home light and happy. I couldn’t believe it. I asked him what happened. He said, ‘It was people asking about who [I] was as a person. They didn’t just focus on my mistakes,’’” Carney said.

Senior Ryan Wilson joined the Peer Solutions team last February and has enjoyed his time serving the community over the past eight months. Although he does not have a history of delinquency, he has found his time with YTJ rewarding.

“I’ve enjoyed giving back to the community,” Wilson said. “I’d say [the peer group is] more privileged than [those who come through Peer Solutions], and us being able to give back to them is a big deal.”

According to Carney, the traditional adversarial punitive system that punishes students for mistakes rather than helping them can reintroduce trauma in youths. Unfortunately, this method is often the default system in place in schools.

“If a kid’s acting out in middle school, what they’re actually doing is saying in a convoluted way, ‘My life stinks. I’m in pain. This is how I’m letting you know.’ And what do we do? [We have] detention [and] suspension. That’s punishing trauma. What we have to do is heal trauma, because if we punish trauma, those kids grow up [to be] traumatized adults,” Carney said.

Antonio Zavala, who works with YTJ and Peer Solutions as a Bilingual Restorative Justice Associate, was expelled from Terra Linda High School in his adolescence and had to deal with the traditional system of punishment and probation.

“I spent a lot of nights and days in Juvenile Hall [with] a higher level of adult supervision [than normal attendants]. If I was stopped by a law enforcement officer and I was asked whether or not I was on probation, I had to say ‘Yes.’ That gives the probation officer the authority to go ahead and search me,” Zavala said. “What many of us consider as our basic rights to privacy [were] stripped from me as a minor. And, for that reason, I had to deal with a grimmer reality [very young].”

For the past year and a half, Zavala has worked alongside Carney with Peer Solutions. According to Zavala, the work in helping bring young people back to their feet, especially those who are Latinx like himself, has been incredibly rewarding.

“[With] Latino youth who are going through the juvenile justice system, I can reflect back on my own experience and realize that once you’re in the juvenile justice system, probation is a vicious cycle where you have these restrictions that really limit how much freedom you have,” Zavala said.

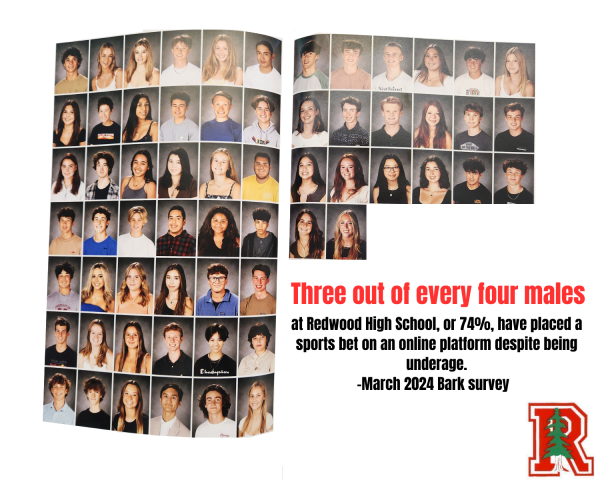

Black and Latinx youths are the most prevalent demographics that go through YTJ. According to the California Department of Education, in the 2018-2019 school year, the suspension rate for Black or African American students was 17.9 percent, while they only made up 1.4 percent of school populations. In comparison, the suspension rate of white students was 2.4 percent while they make up 70.9 percent of the school population. Carney has worked with the administrations of many Marin public schools on how to implement harm reduction practices such as suspension alternatives and alcohol and drug safety skills training into their own justice systems to try to close this racial divide. However, the upkeep of these practices has been inconsistent.

Black and Latinx youths are the most prevalent demographics that go through YTJ. According to the California Department of Education, in the 2018-2019 school year, the suspension rate for Black or African American students was 17.9 percent, while they only made up 1.4 percent of school populations. In comparison, the suspension rate of white students was 2.4 percent while they make up 70.9 percent of the school population. Carney has worked with the administrations of many Marin public schools on how to implement harm reduction practices such as suspension alternatives and alcohol and drug safety skills training into their own justice systems to try to close this racial divide. However, the upkeep of these practices has been inconsistent.

“San Rafael [High School] has a very conscious superintendent who really is interested in equity for the Latinx population,” Carney said. “Redwood has a problem with suspending kids of color. Redwood never really wanted to address [the issue] wholeheartedly. Most recently, I believe, they were hoping that their Wellness program would have addressed it. It has to some degree, but Redwood has been resistant [to its full effects].”

Redwood Principal David Sondheim attributes these statistics to the small population of Black students at the school. Although he describes the system of suspension and resolving conflicts as restorative in nature, he sees it as something they are still working to improve.

“[This data] identifies an area for us that we’re in the process of still trying to work on,” Sondheim said. “We help the students who may have made a mistake learn from that and we help them then restore the damage they may have created… While it may not heal things back to what they were before, hopefully, it’s a step in that direction.”

Despite Redwood’s efforts to make equity more present at school, racial disparity is prevalent at Redwood and in Marin as a whole. Senior Olivia Letts has dedicated the past three years of her time at Redwood to fighting racism in the Student Leadership Antiracist Movement (SLAM) class. This year, she hopes to bring restorative justice to Redwood’s punitive system.

“This [project] is preventative. Not [because] Redwood is the most needed place to have a restorative justice plan, [but] because there are a lot of other schools in places outside of Marin that [need help to] stop the school-to-prison pipeline,” Letts said. “I still think students of color are regulated differently and are disproportionately affected by our system of discipline.”

From YTJ to SLAM, there are significant efforts from multiple groups to abolish the school-to-prison pipeline, specifically in Marin. Although some students are resistant to restorative practices, Zavala believes that with its help, they are capable of making it to the other side.

“Every young person is going through their own individual journey that is very different from one another. But I always tell [these kids], ‘Trust the process. Whether you’re here to just get probation off your case, or you’re here to make sure the school doesn’t suspend you, give it your best shot,’” Zavala said.

Abby Shewmaker is a senior at Redwood and a Senior Staff Writer for the Bark. Previously, she has served as a News and copy editor. She loves her guitar,...