COVID-19: The ultimate (standardized) test of college admissions

June 8, 2021

Over the past few years, the college admissions process has evolved dramatically. The Varsity Blues scandal of 2019 exposed the vulnerabilities of standardized testing and the customs that favor wealthy students in the admissions process. The following year, colleges were forced to reevaluate their policies more significantly when COVID-19 threw a wrench in many applicants’ plans, setting a new precedent for test optionality.

In April of 2020, Gov. Gavin Newsom announced that all California K-12 public schools would remain closed for the rest of the school year as a result of the pandemic. For the class of 2021, that announcement implied a majorly limited Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) and American College Testing (ACT) testing season. Senior Gabriela Rosenfeld, who recently accepted admission to the University of Southern California (USC), witnessed the struggle to secure a seat for a standardized test after closures firsthand. Except for going out of state, Rosenfeld tried every possible option to take a test, as she had scheduled three different ACTs in San Francisco and one SAT in Sacramento, all of which were canceled. While many students traveled to states with fewer lockdown restrictions in order to take the highly coveted test, Rosenfeld did not see that as an option.

“It was frustrating to know that my friends were taking [the test] out of state, and I was super uncertain if I could take it,” Rosenfeld said. “The entire time I was questioning if I should keep studying because there was such a high risk of it getting canceled again.”

Across the country, standardized testing sites were closed and students stressed. However, according to Compass Education Group founder and executive director Bruce Reed, California suffered the highest rates of test site closures due to the state’s lockdown orders. Consequently, the demand for Compass’ services decreased in California but sustained nationally.

“That drop [in students seeking test prep] was proportional to the drop in open test sites and really correlated with the students’ inability to test. Kids did not just give up on tests voluntarily. They were forced to give up on the tests,” Reed said.

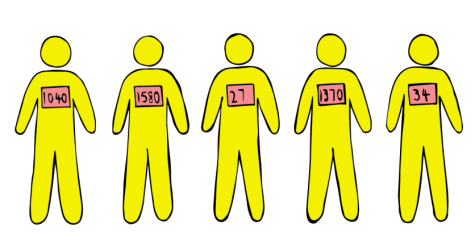

With such discrepancies in test availability across the country, the vast majority of colleges and universities transitioned to test-optional admissions policies. According to The National Center for Fair and Open Testing, only 1,050 schools, approximately one third of the four-year colleges in the United States, offered test-optional admissions in September 2019. By September 2020, six months into the pandemic, over 1,600 schools had implemented test-optional policies. Prior to COVID-19 lockdowns, there was already significant momentum in college admissions towards going test-optional, and the limited testing only hastened the change for the schools previously considering the transition. Additionally, many of the colleges and universities that expressed no desire to go test-optional were forced to convert by the pandemic as well, at least temporarily. The director of admissions at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), David duKor-Jackson, explains that MIT converted to test-optional but still wanted students to submit their scores if they had them.

“If someone couldn’t safely take the test, it seemed like an unfair requirement to make somebody try and meet that. We also didn’t want to force people into an unsafe situation by having them have to go get a test when they couldn’t take it safely,” duKor-Jackson said.

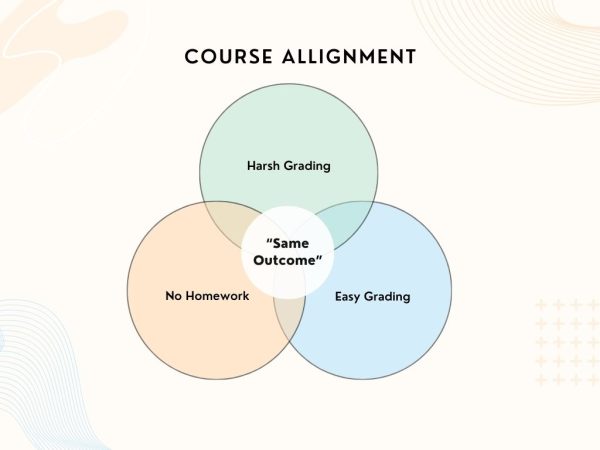

As a result of these policy changes, only 46 percent of students who applied through the Common Application in 2020 submitted test scores, a strikingly

low percentage compared to the 77 percent of students who sent colleges their scores in 2019. In most cases, duKor-Jackson believes whether a student submitted a test score or not had little effect on their admission.

“In the absence of a score, we needed to find something else that would give us confidence [in an applicant’s academic strength], which is the stuff that we would look at anyway. We are looking at the curricular rigor, [seeing if they] have taken the necessary coursework that suggests that they can come to MIT and do well in the things that they need to do well in,” duKor-Jackson said.

Although the usage of standardized tests differed from school to school, there were a few notable trends across the country. According to a newsletter sent out by college admissions expert and New York Times best-selling author Jeff Salingo, students applying with scores to business and STEM programs were admitted at a higher rate than those applying without. Similarly, at schools with extremely low admissions rates, students who applied with test scores were often given a 20 to 60 percent edge in admissions. Emory University reported a 17.94 percent admission rate for students with test scores compared to 8.06 percent without them. However, directly correlating test scores to admissions advantages could be misleading, as students with high test scores often boast a strong academic record as well. The bottom line is that at schools without an extensive history of test-optional admissions, test scores helped students’ overall case. Reed agrees that testing can be beneficial to applicants at competitive schools.

“When a reader opens up an application, she has a lot of questions that she is trying to find answers to and a test score just answers another one of those questions,” Reed said. “If she sees two applicants that look identical otherwise, but one has a strong test score, [the score] is yet another piece of concrete information that means something, and it makes that decision a little easier.”

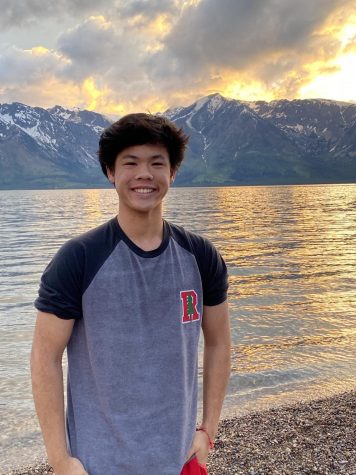

Senior Jordan Mann, who plans to attend Dartmouth College next fall, was able to take the SAT and chose to submit his scores to colleges as definitive data that could help him stand out in competitive admissions pools.

“I think scores generally help because they are a quantitative point in a very qualitative process,” Mann said. “For a lot of the more exclusive [schools], I think having a test score is yet another way to differentiate yourself.”

On the other hand, Rosenfeld applied to the USC Marshall School of Business without scores to show. Despite not being able to take the standardized test, she believes that a score may not have been beneficial.

“There are some people with a really low [grade point average] (GPA), and a nice test score would have benefitted them. Because I had a solid GPA, I would’ve had to have to get a really high test score to match it, and that would have been really difficult,” Rosenfeld said.

What test-optional policies did notably impact, though, was the number of applications colleges received. Nearly every selective college and university in the country experienced a record-breaking surge in applicants for the 2020-2021 admissions cycle. While competitive schools like Harvard University received 42 percent more applications than a typical year, Colgate University experienced the highest increase in applications with a 102 percent increase. The University of California schools, which went test-blind indefinitely after a legal case, saw an 18.2 percent increase in applications. Without requiring test scores, students who previously were discouraged from applying to colleges with high median test scores applied this year believing they may have a shot at acceptance. In addition to hopeful applications, Reed believes that another factor influenced applicant rates this year.

“I think there were two sentiments happening at once across the country. There was hopeful optimism and the opposite, fear,” Reed said. “Both of them led to the same behavior which was to apply to more schools.”

The fear Reed proposes comes from the transitive thought process of many students who applied to a school they could never get into if test scores were required. They realized that if they apply to better schools before, then their friends are likely doing the same and the cycle continues. That mindset led students to feel pessimistic and fearful, so many applied to more schools.

Similarly, Marin college consultant Gael Casner believes that competitive colleges saw another rise in applicants because of students’ inability to participate in live events and formulate a list of schools that were a personal fit.

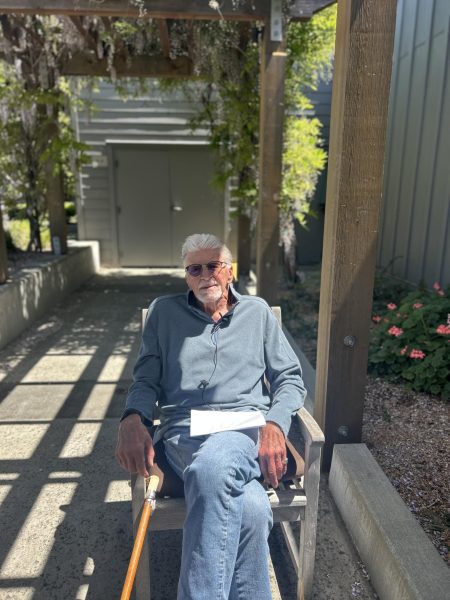

“I think it was really stressful, and the real stress came in not being able to get on campuses to make decisions. They didn’t get a chance to see a lot of these colleges, and if they snuck onto campus, they sure didn’t get the warm and fuzzy embrace that they would have for a normal year. So, most of my kids made a decision somewhat in a vacuum,” Casner said.

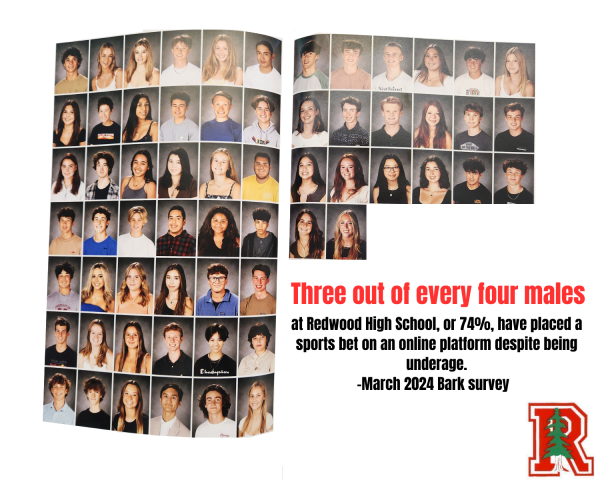

Aside from the changes in the past year, the college admissions process has held up its infamous history of supporting privileged students while hindering the academic potential of less-privileged students. From prioritizing legacy students and recruited athletes to requiring test scores, policies that fuel much of the admissions process are favorable to certain demographics. In going test-optional, many colleges and universities hoped to increase diversity in their applicant pool.

However, researchers are finding that dropping testing requirements is not substantially expanding the number of low-income students or students of color applying to college. A study published by the American Educational Research Journal in April 2021 found that applications from Black, Latinx and Native American students only increased by approximately one percentage point when colleges transitioned to test-optional admissions. So while test-optional admissions open up a door for a handful of low-income and minority students, the increase is not as substantial as most would expect. Reed thinks that going test-optional is an easy way for schools to embark on the diversity pursuit, but their work to support underrepresented communities should not stop there.

“The hard work comes after you get rid of the test scores. It is the stuff that does not make headlines, and it is not an easy policy that you just change,” Reed said. “It’s really society coming to grips with what is causing students to under-perform systemically.”

With so much work left for colleges and universities to take action on, the future of standardized testing and its application in admissions is uncertain. Some schools, like the University System of Georgia, have already announced the reinstatement of SAT and ACT requirements for the 2021-2022 admissions year. However, Reed anticipates that the majority of colleges and universities will remain test-optional going forward.

“I do not know that you are going to see [testing] requirements come back, but I think you’re going to see the expectation come back,” Reed said. “You do not have to do a summer job. You do not have to have an extracurricular activity. Those are not required, but they are expected.”

Regardless of test-optionality, Casner fears the precedent set with the removal of standardized tests will limit an admission officer’s ability to fully evaluate an applicant.

“The more pieces you can give a school, the better. If you take one piece away like the SAT or the ACT, [admission officers] can still see a picture. The more pieces you take away, though, the harder it is to see a kid,” Casner said.