Editorial: Cultivating engaged learning

How we can improve our remote and physical classroom settings

December 17, 2020

It’s now mid-December and in-person learning feels like a bygone memory. Distance has become the most defining aspect of our education. Remote learning has minimized our comprehension and retention of academic concepts, bringing the shortcomings of our education into full view. Student immersion is seemingly at an all-time low, but distance learning isn’t the only culprit: our educational structure has long been the foundation of this issue. Seeing that numerous societal practices and structures have been challenged over the course of the pandemic, it’s only fitting that we examine this unengaging learning model as well. Online school has arguably been as hard for teachers as it has been for students, but if teachers can better foster connections within our content starting now, we’ll be more equipped to implement these changes upon our return to the physical classroom.

It’s now mid-December and in-person learning feels like a bygone memory. Distance has become the most defining aspect of our education. Remote learning has minimized our comprehension and retention of academic concepts, bringing the shortcomings of our education into full view. Student immersion is seemingly at an all-time low, but distance learning isn’t the only culprit: our educational structure has long been the foundation of this issue. Seeing that numerous societal practices and structures have been challenged over the course of the pandemic, it’s only fitting that we examine this unengaging learning model as well. Online school has arguably been as hard for teachers as it has been for students, but if teachers can better foster connections within our content starting now, we’ll be more equipped to implement these changes upon our return to the physical classroom.

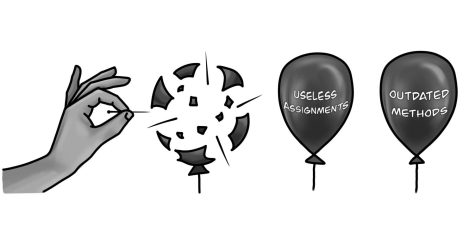

One of the most common critiques regarding education in the United States is that we still abide by the “factory model of education.” That is, education mimics vocational school, which was designed to train factory workers during the industrial revolution. The vast majority of classes follow this same format: learn material, memorize said material and regurgitate your memory of the material in the form of an assessment. This format is incredibly repetitive and stale, yet mastering it is all that matters in our current system. Although teachers aren’t to blame for factory model learning, they have the power to make positive change in their classrooms: here are a few ways that teachers can further engage their students moving forward.

Content covered in our classes often feels inapplicable in the real world, and now that we’re physically detached from such a world, we’re even more out of touch with the current curriculum. In a course like math, learning the computational skills that calculators are programmed to do feels like an even more futile task than normal. The list of outdated course material goes on and on. But we’re not in the business of designing a new curriculum; instead, we can rejuvenate what we have in place.

If students are more frequently empowered to choose the content they are taught (within reasonable bounds), they may take more ownership of, and have more interest in, their work. This is not to say that students should be able to selectively choose the concepts covered in their courses, but research projects could gain a dynamic edge if students were able to choose what they explored within a given topic. With so many events happening in the world right now, coupling our learning with exploration of current issues could reinvigorate our resolve twofold.

Furthermore, classes should not only provide students with real-world insight but also a sense of purpose and meaning. When students get a grade on an assignment, they often erase the content from memory, as it means little more than checking off the completed box; now, more than ever, it seems insight and genuine immersion in subject matters are low on students’ priority lists. This lack of true interest in course material most clearly manifests itself in reluctant group work, whether it takes place in tortuous breakout rooms or in real life. To combat this, teachers could elect group members to different positions: delegating a note-taker, a discussion leader, a researcher and a group speaker, for instance, would instill a sense of purpose and responsibility in class each day.

Oftentimes, working for a bigger purpose can motivate students to not only do their work, but take pride in it. In Bark, because we know the community will be reading our publication, we hold ourselves to a higher standard than we would in a typical course. To achieve this in other classes, teachers should consider having students submit essays, presentations, videos or other project forms to local newspapers, publishing sites or a Redwood-created forum. Such a forum could showcase student work in a similar manner as an art gallery, encouraging students to submit their best work. Doing so would make their work relevant to the real world while also giving it a tangible place in such a world, generating meaning beyond the grade.

Online school is draining for all parties involved, and it seems we’ll be in it for the long haul this year. Teachers have made sacrifice after sacrifice to improve online education for their students. We’ve seen them calming down their crying children while giving a lecture from home. We’ve watched their expressions sink when faced by silence and turned-off cameras after asking the class a question. We’ve heard their announcements about the after school office hours they’ve set up to help our learning retention and review course material. We know how hard teachers have worked this year, and our suggestions are in no way meant to insinuate that they are failing us right now; rather, they seek to enhance all the work they’ve already put in for us. This pandemic has been a tumultuous time — let’s also make it a fruitful one.