ADHD and dyslexia: exploring learning disabilities in the classroom

June 4, 2020

Reading, studying, listening and learning. These skills are necessary to succeed as a student, and early education attempts to instill them in kids. For individuals with learning disabilities, however, classroom etiquette may not come as naturally or even at all. Learning difficulties are surrounded by stigmas and often considered synonymous with “special needs,” but actually encompass a variety of comprehension issues. These issues may range in extremity, but most prevent students from fully thriving in the traditional education system. Dyslexia and Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADD and ADHD) are two of the most common learning disabilities, but with symptoms that mainly arise in academic or work environments, they can go undetected for years. When they are diagnosed, their impacts are often understated.

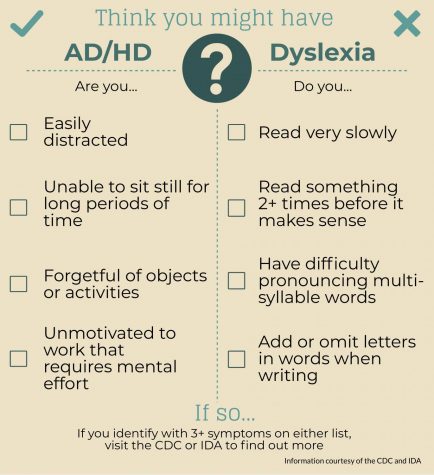

According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), 9.4 percent of American children aged two to 17 years old have ADHD. The disorder is characterized by tendencies toward distraction, inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity, according to the International Dyslexia Association (IDA). Dyslexia is a language-based learning disability where individuals have difficulties with language skills such as reading, writing, spelling and word pronunciation, according to IDA. Dyslexia and ADHD are closely intertwined; students with either often experience both reading and listening difficulties. The IDA estimates roughly 30 percent of individuals with dyslexia also have ADHD. With both conditions, paying attention is often more physically demanding and can cause fatigue. Junior Lilly Miller has both ADHD and dyslexia, which pose a challenge in academic environments.

“[ADHD and dyslexia] both limit how easy it is to do work. Outside of school, I see a lot less of their effect, but definitely within school it makes [assignments] take a little bit longer. [I] have to think a little bit harder about doing everything,” Miller said.

Despite there being a recent surge in AD/HD diagnosis, the condition often goes undetected, especially due to stereotyped differences between genders. According to the CDC, 12.9 percent of boys and 5.6 percent of girls are diagnosed with ADHD. However, the rates among adults are fairly equal according to Psych Central, demonstrating how less prominent symptoms like inattentiveness often lead fewer women to go undiagnosed. Despite seeing others with the condition and identifying with their symptoms, Miller was only recently diagnosed.

“I haven’t been diagnosed for super long. I kind of had a sense that I had it and it was hinted at in some testing that I did but I was officially diagnosed a month or two ago,” Miller said.

On the other hand, dyslexia is severely underdiagnosed, as 15 to 20 percent of the population show some signs of dyslexia and would benefit from treatment. It can also manifest as a specific difficulty with writing or math, called dysgraphia.

Freshman Svea Munson has been treated for her dyslexia since fifth grade, when she was diagnosed.

“At first I thought I had some sort of spelling problem. I had trouble understanding what teachers were trying to say when it was written down…What I usually do is switch up letters like ‘a’ and ‘e’ that look really similar,” Munson said.

For Munson, the transition to public Terra Linda High School from Marin Primary Middle School where she was able to receive one-on-one support has proven difficult, especially when taking notes or reading in class.

“I still have good grades…it’s just more challenging. [Reading] takes longer and I have to read through things three times for them to make sense, like questions on tests,” Munson said.

While Munson has been able to develop her skills over time, learning to communicate with peers and teachers has proven most valuable in helping her succeed as a student.

“Advocating for myself and saying that I need help used to be really challenging. Now that I’ve just gotten more comfortable with teachers, I can ask them questions, whether it’s after class or [by] emailing them,” Munson said. “I’ve become more of a self-advocate because I usually need help.”

Munson does not have an Individualized Education Plan (IEP), which is a formal learning plan schools develop to support students with disabilities and improve their academic abilities. Students with dyslexia and AD/HD often have highschool-specific IEPs called 504 plans to give them more flexibility based on their school needs, such as increased time for tests or assignments.

According to Miller, motivating factors are different and much less present for students with learning disabilities than those without. For Miller, sitting down and committing to work is one of her biggest struggles, and staying on track once she has started is challenging as well. However, experimenting with AD/HD medication such as Ritalin helped to regulate these symptoms.

“It was less of a battle to start doing work, and then once I was doing it, it felt rewarding to do the work. Before it didn’t really feel rewarding,” Miller said.

Medication is one of the most popular treatment options for AD/HD, with approximately 62 percent of children with the disorder taking prescription drugs, according to the CDC. Three out of four U.S. children with AD/HD receive some form of “treatment,” despite the condition not always being treatable. Behavioral therapy is another avenue available for handling AD/HD and can help subside some of the impacts of having a learning disorder.

Dr. Marianne Shine is a local psychotherapist and drama therapist, specializing in counseling for individuals of all ages through creative expression. According to Shine, learning disabilities like AD/HD and dyslexia can leave affected students feeling like they do not fit in.

“Our education system is set up in a way where everyone has to meet certain criteria by the end of the year and the way people learn is not all the same…I think the frustration and depression comes from trying constantly to fit in and match what everyone else is doing, and it doesn’t fit,” Shine said.

According to the CDC, 64 percent of individuals with AD/HD have a coexisting mental, emotional or behavioral disorder. According to Shine, having a disability makes an individual much more susceptible to negative messages from neurotypical people and feeling out of place. Messages and feelings like these in large quantities contribute to self-deprecating thoughts, which can lead to the development of mental illnesses like anxiety and depression.

“If you’re the kid who’s got AD/HD or dyslexia, and your siblings, friends or community keep making disparaging comments, you’re going to start internalizing them and think, ‘Maybe I am stupid’ or ‘Maybe there is something wrong with me,’” Shine said. “When you internalize that voice, you don’t need the outside negative voices anymore—you’re carrying it inside yourself. And that’s how the depression starts to grow because you’re defeating any possibility of moving forward.”

Behavioral counseling or therapy can help ease these conditions or prevent them altogether if they are caught early enough. Therapy helped Miller to accept her differences instead of comparing herself in the classroom.

“Knowing what causes these things, knowing that I take a little longer because of AD/HD or something, and just kind of being like, ‘Okay, that makes sense now, I understand why I work a little differently’ makes me feel a little less ostracized,” Miller said. “Being able to talk about it with an expert and work through different things has definitely been helpful.”

For students with learning disabilities, their experience in the classroom, social life and mental health are all affected. Daily activities that come easily to neurotypical people pose inherent challenges for anyone with a learning difficulty. During the shelter-in-place, it can be especially difficult to stay on top of schoolwork and remain mentally stable with or without a disability, so prioritizing mental health and regulating habits is more important than ever. If you think you might have AD/HD, dyslexia or another learning disability, visit https://dyslexiaida.org for more information.