Mental illness in the LGBTQ+ community

February 7, 2020

“One time, I came out to a girl at a party as bisexual and she scooted her chair away from mine. I was filled with anxiety for the rest of the night.”

This was the experience of current junior and Sexuality and Gender Alliance (SAGA) club president Natalie Pemberton. Members of the LGBTQ+ community experience similar microaggressions daily, which can take a serious toll on their mental health. Repeated offensive actions such as these toward individuals amount to serious self-doubt and trauma that, over time, can lead to the development of mental illness.

In 2015, almost 30 percent of students in grades nine through 12 nationwide reported feeling sad or hopeless for at least two weeks in a row, an indicator of depression, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). However, not all communities are subject to the same rates of mental illness—a number of social factors differentiate them. Certain groups, such as the LGBTQ+ community, struggle with unprecedentedly higher rates than others.

When everyday microaggressions and the sinking feeling of “I don’t belong” are added to an already-chaotic high school life, individuals can become more prone to mental illness. The queer community and other minority groups deal with these conditions more than most, according to Fel Agrelius, youth program coordinator at LGBTQ+ support organization the Spahr Center. She attributes the prevalence of mental illness in marginalized groups to the isolation and discrimination they face.

“This world is just simply not build for LGBTQ+ people because of expectations around what a normal relationship should look like, which bodies are supposed to dress in which ways, and more.” Agrelius said. “It sucks to move through the world and not be part of the norm, to not see yourself in popular culture and to not have your gender or sexuality respected.”

As the youth program coordinator, Agrelius works on outreach and education both in schools and for the community. Despite the increased support queer Redwood students have gained in recent years and continue to recieve with resources like the

SAGA club, Agrelius still attributes the disproportionate number of mental illness in their community to unfair treatment and microaggressions toward LGBTQ+ individuals.

“I think that if we were living in an equitable society, [mental illness and sexuality] wouldn’t have a direct link. But because we’re a marginalized community, it takes a profound amount of resilience to not be weighed down by what’s happening,” Agrelius said.

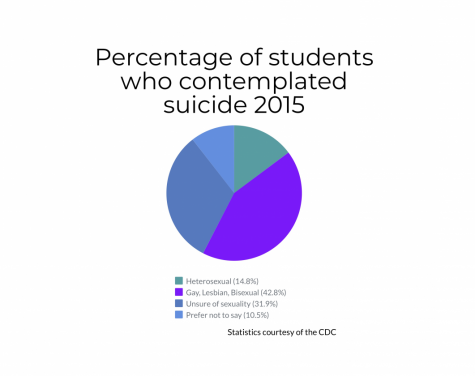

In 2015, 89 percent of students nationwide identified as heterosexual, eight percent identified as homosexual or bisexual and the remaining three percent were “not sure” of their sexual identity, according to the CDC. At Redwood, these statistics are almost the same according to a 2018 Bark survey where 85 percent of students self-reported they were heterosexual, two percent identified as homosexual and eight percent were bisexual.

Despite their low quantity, those within the eight percent in the CDC survey experienced up to double the depression rates of heterosexual students: 26.4 percent of heterosexual students experienced a two-week period of major depression in 2015 as compared to the 60.4 percent of gay and bisexual students who felt the same.

Stress can be a decisive factor in the development of mental illness, according to licensed Bay Area psychotherapist Bridget Whitlow. Discrimination and lack of acceptance are major causes for this stress, as well as other mental issues.

“If our parents or our loved ones reject us, of course that’s going to feel awful. That’s going to increase those environmental stressors of and then maybe even help develop internalized stigma or discrimination,” Whitlow said. “If they think [their sexuality] is wrong and they should be embarrassed, that could increase chances of depression, isolation, anxiety—it could go in any direction.”

As part of the LGBTQ+ community, Agrelius disclosed that her own experience with sexuality can be “a heavy weight to carry,” due to the microaggressions that she and other members of the community routinely face. Microaggressions are physical or verbal acts of discrimination against a marginalized community that are often subtle or even unintentional.

“A misunderstanding of what our identities are, [others] not understanding what it means to be pansexual or bisexual and then hearing a bunch of microaggressions around that [can be very detrimental],” Agrelius said. “And if you aren’t living somewhere where your parents love and understand you, then it’s very likely you’re going to be depressed or have some kind of mental health issues.”

The opinions of the SAGA club parallel Agrelius’ outlook. The microaggressions that permeate high school culture can deeply affect students’ self-confidence and start a cycle of negative thoughts in the developing brain.

“When we see homophobia, we can react with anger because we know it’s their fault. We can get mad. But when we experience a microaggression, we internalize it and see it more as on us. And that can create a downward spiral of thoughts that can lead to mental illness,” Pemberton said.

Without the threat of being cast out by one’s family or being bullied at school, coming out without trauma could be possible, according to Agrelius. However, the instances where a gay boy is abandoned by his family or a trans girl is heckled in the hallway are common even today, perpetuating the cycle of microaggressions, stigma and mental illness in the queer community.

If the divide between the treatment of the LGBTQ+ community and the rest of society lessened, the disparity in mental health could decrease as well, according to both Agrelius and Whitlow.

“It’s in those daily moments of speaking up and standing up,” Whitlow said. “And just in those minor ways we can really help to change the culture [of homophobia].”