Homecoming tackles gender norms as the tradition becomes more progressive

November 8, 2019

The moment the entire week has built up to is finally here: enthusiastic students and parents fill the football stands while the homecoming court proudly walks onto the field waving eagerly at the crowd. Each member is presented with a box containing a rose, either white to indicate victory or red to indicate otherwise. Tension mounts and silence resonates. The winners are…two kings?

Unbeknownst to some, Redwood changed their homecoming standards two years ago to allow for any combination of homecoming winners. Rather than the traditional king and queen––male and female––Redwood now elects two homecoming royalty members, allowing any combination of genders to be crowned.

Redwood’s adaptations

In recent years, Redwood has worked to promote inclusivity within the student body. The Leadership 2020 class Instagram account instructed seniors to vote online for their court based on a series of strengths that they believe illustrate a Giant regardless of their gender: personality, school involvement, academics, athletics and artistic skills.

Attempting to promote inclusion, Redwood changed its homecoming policy in 2018 so that the winners do not have to be strictly one male and one female.

A debrief of homecoming led in 2017 by Leadership teacher David Plescia brought to light the need to make these accommodations. The Leadership class started to implement changes to the court the following year, allowing for representation of people of non-traditional sexuality and gender.

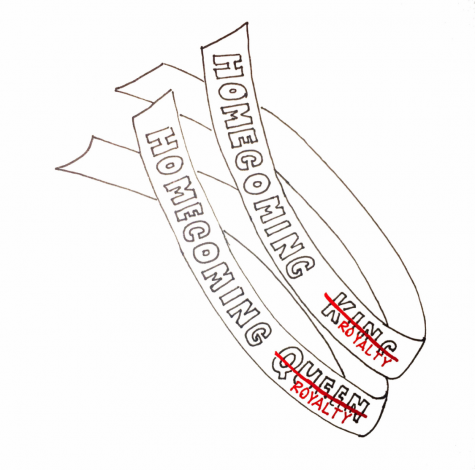

Prior to this, seniors selected their favorite pair made up of a king and queen. The couple was crowned and given matching sashes with their titles. This has since been updated, with sashes that now read “Royalty.” Fellow Leadership teacher Melissa Boles, who was a grade-level advisor when this policy was changed, believes that the alteration was necessary to create an inclusive environment for homecoming court nominees.

“Those old terms [of king and queen] created the appearance that you were only eligible if you were cisgendered, which of course is not the case. A big reason why we removed that court royalty language was to signal the inclusivity of the event. It’s open to anyone, however they identify,” Boles said.

Changing traditions as society transitions

The tradition of homecoming can be traced back to a University of Missouri football game in 1911. With the addition of a parade and school rally to supplement the game, the intention was to encourage alumni to visit the school. High schools and universities around the country have since adopted this custom.

For decades, homecoming has taken a similar structure among high schools: a football game both alumni and students attend, the crowning of a king and queen from the elected homecoming court and a dance in the evening. Some high schools, including Redwood, also dedicate the week prior to the game as “Homecoming Week,” where students dress up for specific spirit days. Although these traditional aspects have stayed constant, some traditions have evolved since the original court crowning.

There have been several challenges to gender-based homecoming traditions. Especially in California, an increasingly diverse gender and sexual spectrum has led to changes in laws, which has generated more widespread acceptance of individuals who do not identify with traditional binaries or orientations.

According to the Williams Institute, a public policy research entity based at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Law, 5.3 percent of California’s total population today identifies with the LGBTQ+ community. Additionally, a 2017 Williams Institute study categorized 27 percent of adolescents in the state of California do not fully associate with the gender they were born with. Non-binary senior Leila Malone, who identifies as they/them, believes that both Marin and Redwood’s more progressive atmosphere has created a more welcoming environment for people in the LGBTQ+ community.

According to Malone, LGBTQ+ members speaking their minds has further eased the idea of a non-cisgender royalty winner as social and gender-related norms present in homecoming customs are increasingly challenged.

“Because people in [the] LGBTQ+ community are more visible, I think that [the LGBTQ+ movement] is slowly moving forward to people being comfortable… If we have a gay king, lesbian queen or non-binary royalty, that would be wonderful, but change happens slowly,” Malone said.

Perceptions at Redwood

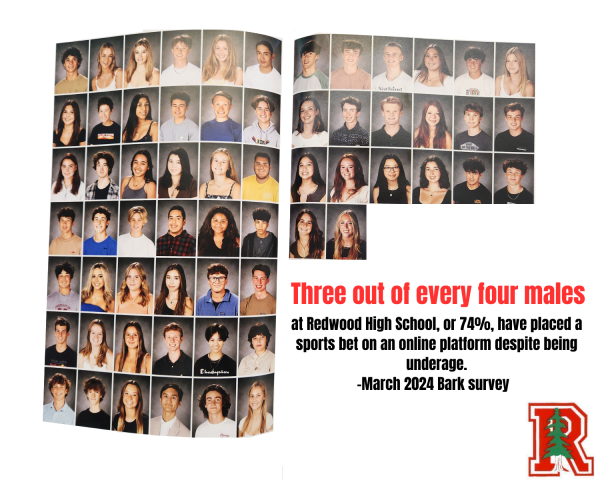

There are some students who believe that the changes to homecoming are violating tradition. According to the 2019 October Bark survey, 57 percent believe that the shift breaks routine. However, of those who believe that the shift violates tradition, 56 percent are personally fine with the change.

There is still a large population at Redwood who do not support the change. While the main motivation behind this transition was to generate inclusivity of all students, junior Sam Bonder, who experienced homecoming at Woodward Academy in Atlanta, Georgia before transferring to Redwood in 2017, believes that it will eventually do the opposite.

“I get that they want to see more inclusivity, but the tradition is king and queen. That’s how it always has worked,” Bonder said. “I think that there’s something special when you pair up people of other genders rather than just two guys because then it really does become a popularity thing.”

Breaking homecoming tradition, 2019 was the first year in Redwood’s history that a female did not win.

When the winners are a king and queen, Bonder believes that homecoming is more representative of the student body as a whole.

“If [there are] two guys, and a lot of people like those guys, they’re both going to get voted in. That might happen for years on end, where it might just be two guys, might just be two girls, when it should be split. At least everybody feels like they have a chance and it’s more representative [with a king and queen],” Bonder said.

Conversely, Malone believes the modernization of homecoming trends override the importance of tradition.

“[Ending tradition] is not a good reason for things to stay the same,” Malone said. “I think a lot of people are afraid of change in general and that can come off as hate, but it honestly could just be fear. For me, I don’t think [changing the tradition] is that big of a deal.”

Although Malone appreciates Redwood’s attempt to adjust to a changing society and the application of this into the homecoming court, they believe that the likelihood of the school electing two of the same gender or a member of the LGBTQ+ community to the royalty is slim.

“As much as [the LGBTQ+ community] wants to be more out there, straight people are still in the majority,” Malone said. “I think people are going to be more likely to choose a couple between men and women. I think that’s more likely than choosing two kings and two queens, but that doesn’t mean it can’t happen. And I do appreciate that [two kings or two queens] is a possibility.”

Beyond Redwood

Across the country, homecoming traditions and culture varies. At Half Moon Bay High School, they have adopted non-traditional arrangements for homecoming. These include allowing non-cisgender individuals to win homecoming titles. Two years ago, Raven Chalif, who goes by they/them pronouns, was crowned king.

“I was just a little nervous because I was all dressed up in a suit and people definitely knew that I wasn’t a regular boy…At the football game, I was questioning what I was really doing there. Like, did I even have a chance because I was standing next to all these boys?” Chalif said. “Am I deserving of it? Would people actually vote for me? Then, actually, I didn’t expect it at all, but everybody just started erupting in cheers when they called my name. It was really crazy.”

For Chalif, their school’s move to a less gender-conforming homecoming holds a greater meaning for them.

“It’s important because even something as unimportant as homecoming should be integrated and available to everybody. I think that that speaks to other more important issues,” Chalif said. “If there [are] people who are more ignorant or more educated about gender, gender inequality, non-binary genders or anything like that, then it’s a starting point for education on that.”

Other schools across the country adhere to original Homecoming traditions. At Woodward Academy, it is important to preserve the traditions because of the active student participation and ardent support for Homecoming as is, whereas Redwood has the opportunity to stray away from these traditions because of its lesser student involvement, according to Bonder. In Oxford, Mississippi, the spirit among the student body is intense and the homecoming festivities receive significant engagement on behalf of the tradition they represent, according to Caroline McCready, a junior at Oxford High School. She also believes that homecoming is important at her school because it unites the student body, stresses a common identity and facilitates unique interactions among students.

“Everybody at Oxford has a reputation of being ‘too cool’ to do these certain things. So [homecoming] is a week that everybody can just branch out, do their things and have fun. Also, it’s fun to get everybody together,” McCready said. “It’s great for friendships and unity where everybody gets to be together.”

At the end of the day, Chalif says, homecoming is supposed to promote school spirit and unity between all students, not just those in the majority.

“Homecoming isn’t the most important thing, but the most important part of it is to have fun. If you can’t have fun, I feel like something needs to change,” Chalif said. “Something did change for my school, and I was able to have a pretty amazing senior year.”