The juggling act for student-athletes

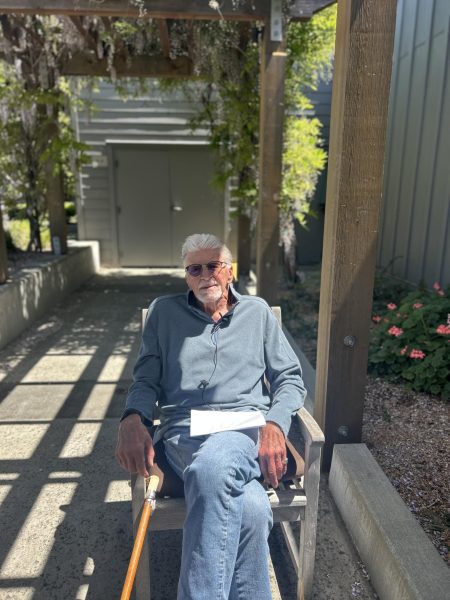

Don Schwartz, the coach of Finn Aune and Jackson Mason, watches over the young athletes during practice

July 4, 2019

Many believe the life led by student-athletes is a privileged one, filled with easy acceptances, high praise and endless amenities. With recent college scandals where students and their parents cheated the admission system, acceptances are more scrutinized than ever before. Athletes fall under this spotlight now because of assumed “easier” standards for athletes compared to the average student. In reality, only the most dedicated athletes can make their way to a spot on a Division I team. The taxing schedule of balancing school and sports can only be maintained by the most dominant, committed athletes who are driven by a love for the sport.

For Division I collegiate athletes, many aspects of the college experience are lost due to their athletic commitment. In-season, most Division I athletes are on the road for three to four days every two weeks, meaning they are missing about two academic days every two weeks. Missing two full days means missing numerous assignments, study time, lectures, notes, and opportunities for questions. According to the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), during the season Division I teams are allowed to train up to twenty hours a week, which is essentially the time commitment of a part-time job. In addition to their academic disadvantage, athletes miss out on the social experiences that make college so memorable for others. With about twenty hours a week dedicated to their sport, athletes often have to skip out on parties, time with friends and study abroad opportunities whilst trying to balance academic requirements.

Bill Pennington, a columnist for the New York Times, has commented on the burdensome life carried by student-athletes.

“The life of the scholarship athlete is so arduous that coaches and athletes said it was not unusual for as many as 15 percent of those receiving athletic aid to quit sports and turn down the scholarship money after a year or two,” Bill Pennington said in his New York Times article, “It’s Not an Adventure, It’s a Job.”

It may seem like their sport may be the only safe haven for these extreme athletes; however, sports also serve as a stressor for many of the athletes. According to Athletic Insight, an online journal of sports psychology, research shows that sports add stress for students. Dr. Mary Pritchard, a sports psychologist with a PhD from Boise State University, is one of the writers for Athletic Insight.

“Studies also suggest that athletic participation itself can become an additional stressor that traditional college students do not experience,” Dr. Mary Pritchard wrote in an Athletic Insight article.

A factor for this stress can be found in the confidence levels in college athletes. In high school, many of these now-college athletes were constantly praised for their unique talent, typically only one of a few at their high school to win a scholarship at the Division I level. Once in college, the ‘star’ appraisal fades out as they transition to become one of many. In combination with this new found insecurity, several other factors lead to the damaged psyche of student-athletes.

“Athletes experience unique stressors related to their athletic status such as extensive time demands; a loss of the ‘star status’ that many had experienced as high school athletes; injuries; the possibility of being benched or red-shirted their freshman year and conflicts with their coaches, among other factors,” Pritchard said.

These stressors lead to common trends of mental instability among college athletes. According to Athletic Insight, a recent study found that close to half of the male athletes and over half of the female athletes they interviewed associated stress with their athletic participation.

“10 percent of college athletes suffer from psychological and physiological problems that are severe enough to require counseling intervention,” Dr. Gregory Wilson wrote in an Athletic Insight article.

Although it appears as though becoming a college athlete is what leads to the unanticipated stress, many high school athletes also receive unwanted problems. Finn Aune, a sophomore at Redwood High School and an extremely competitive swimmer, has first handedly faced the effects of a busy athletic schedule.

“If I didn’t swim I would have a lot better grades. It’s definitely hard to manage school and swimming. I fell asleep last period,” Aune said.

Aune swims six days a week with an additional three days in the weight room before school. He feels as though his rigorous athletic schedule has become more of a time demand than his academics, redefining the common perception of student-athletes.

“At this point, I’m more of an athlete than a student. They should call us athlete-students,” Aune said.

Jackson Mason, a University of California-Santa Barbara swimming commit and a senior at Drake High School, feels similarly to Aune.

“I think about my swimming before I do everything. I think about my swimming before I decide what I’m going to eat for lunch, and what time I’m going to go to bed, and who I’m going to hang out with, and what I’m doing to do on the weekend… I’m pretty much willing to sacrifice anything except for friends and family for the sport. My athletics 100 percent come first for me,” Mason said. “Of course I value academics, but my life is based around swimming, not school.”

In addition to the time constraints their sports cause them, Aune has also dealt with some of the mental effects college athletes regularly face.

“I was trying really hard and I didn’t qualify [for a meet] and it crushed my heart. I didn’t go to practice for two days. In the swimming world that’s a really long time. I didn’t make it and I felt so bad. I felt so mad at myself,” Aune said.

Although their value on athletics has been detrimental to other aspects of their lives, both of these athletes agreed they would not be happy doing anything else.

“I’m always tired and I’m always hungry, but I love it. It makes me who I am,” Aune said.