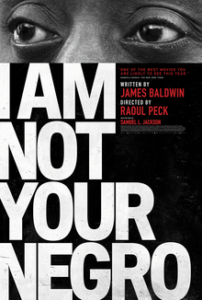

Like many students my age, I’ve seen several documentaries about racism and discrimination in America. But “I Am Not Your Negro” goes well beyond offering just an overview―it defines the causes of racist behavior and proposes solutions for this ongoing problem.

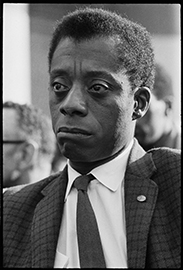

The documentary is based upon the life of James Baldwin, a Black American writer and philosopher who frequently spoke on television and in numerous universities from the 1960s through the 1980s.

Extensive footage of his life exists, so viewers have the opportunity to watch his most searing and pointed commentary on the state of Black civil rights in America in the mid-to-late 20th century. These are the most memorable scenes in the movie because it quickly becomes apparent that Baldwin’s ideas for combating racism are startlingly relevant today. It was thought-provoking due to the fact that it poked at the conscience of White American viewers like me.

Baldwin is a poetic intellectual who defines the source of racism in America as a fundamental moral issue. He questions the maturity and truthfulness of suburban White Americans in a way that is not confrontational, in spite of the message. He expresses himself so well and with so much sincerity that his message can be readily heard, understood and accepted by White Americans viewers.

The film echoes this non-confrontational approach as it lays out the life of Baldwin and his interactions with three very influential Black Americans—Medgar Evans, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. The relentless theme of premature death of one Black American after another (including these three) is a constant and discomforting reality. However, this is a necessary discomfort that I think we all need, as discrimination is still prevalent today.

Director Raoul Peck uses water as a metaphor to illustrate the frequent passage of life into death in Baldwin’s lifetime. As each of Baldwin’s mentors die, their passing is memorialized via rain or the ocean or even by pool water.

These scenes contrast with the violent nature of their deaths in a way that seems to be meant to soothe the viewer before the documentary moves onto the next example of a too-short life. The calm style of the movie echoes Baldwin’s approach to these issues, and makes it easier for the viewer to watch.

Peck also incorporates recent video and photo montages to recognize the timelessness of Baldwin’s message and its pertinence today. For instance, he illustrates Baldwin’s explanation about Black Americans’ fear for their own safety with images of modern day events, such as the Ferguson riots and recent Black shooting victims like Trayvon Martin.

Throughout the movie, Baldwin explains—in speech after speech until he is visibly weary—the “emotional poverty” in America that allows Whites to conveniently disregard the disparities that exist between the races. Baldwin notes that most White Americans do not want to face the fact that many Black people fear for their lives in the United States. Understanding the discomfort of the White American audience on this topic, Baldwin and Peck present these points in a non-aggressive manner, both in speech and via the movie images.

Baldwin also equates the Black American’s social status to that of the American Indian. He notes that Blacks’ lower status in American society has been perpetuated by movies and television shows of the 1960s and 1970s in which all the heroes were White. When he watches these movies, he finds himself also seeing a country that is unable and unwilling to recognize the humanity of non-whites.

Once again, Peck effectively employs film clips to illustrates Baldwin’s arguments. For example, he shows John Wayne endlessly admonishing the Indians in western films to highlight the immaturity and ignorance of White Americans to the plight of other races. This is an interesting analogy that I readily agree with.

To combat White Americans’ ingrained tendency to avoid these issues, the movie ends with a montage of various Black American faces. It pointedly suggests we start changing our attitude by simply looking at Black individuals directly. This effectively goes to the heart of the film’s message about overcoming White Americans lack of desire to interact with and understand their Black neighbors as fellow Americans.

There is great truth to the message that U.S. is still a segregated nation. How many of us know Black Americans and interact with them on a daily basis? Although we supposedly live in a post-segregation era, Baldwin is correct in stating that until it is normal for Black and White Americans to regularly interact in all areas of life—school, work, homes, etc.—then White Americans cannot truly claim to be unbiased.

This film is a very effective tribute to someone who went unrecognized in his own time, while also reminding viewers of the very same discrimination that is still faced today. Like its main character, the movie is insightful and perceptive, and demands more self-awareness from its White American viewers. It’s a worthy and important film to watch.