Marin’s socially progressive nature appears everywhere. It’s in the environmentally-conscious surcharges for plastic bags, the Pride flags waving above schools and storefronts, the teachings of a social justice-oriented curriculum and its blue voting record. However, its democratic lean stops short of low-income housing.

Neighbors of planned low-income developments, which include units designated for households with an income approximately 50 percent of the county’s median income or $93,200, often spearhead the resistance.

Community-led efforts in Belvedere branded the partially low-income Mallard Pointe housing development “Bad for Belvedere.” In Mill Valley, residents belonging to the “Save Hauke Park” organization have waged a three-yearlong campaign against the construction of affordable housing units nearby.

These grassroots efforts are not the only challenge to low-income housing. Legislative obstacles, including State Senate Bill No. 106 from 2017, which exempted Marin from statewide housing quotas, have delayed the creation of affordable housing.

Additionally, since 1970, Marin’s population has expanded four times slower than California’s — by design. Through the ballot box, Marin voters have repeatedly defeated measures to increase the county’s long-term water supply, weaponizing a human need to deter future development. This culminated in the Marin Municipal Water District’s 2021 consideration of banning new water hookups, which would have effectively halted any low-income housing construction.

This resistance, whether systematic or community-led, falls under the “Not In My Backyard” mentality, or NIMBY. As financial expert Dave Shore stated in a previous Bark article, “Everybody wants more low-income housing in someone else’s neighborhood.”

Frequently citing the risk of environmental damages, lowered property values and increased strain on public infrastructure, NIMBY proponents raise legitimate concerns around affordable housing but seldom acknowledge the available solutions and the impacted communities.

Environmental issues can be mitigated with high-density redevelopment, which, according to a 2022 University of California Los Angeles study, in turn benefits sustainability through reduced commutes and emissions.

Considering concerns over property values, a University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill report concluded that, “Despite public perceptions of affordable housing negatively impacting nearby property values, there is evidence to suggest that the impact is minimal if at all.”

The worries surrounding infrastructure and resource strain are the most valid argument of NIMBY-ism. Yet, they neglect the reality that anti-development attitudes shift the burden of providing low-income housing to communities with less of a voice and often fewer resources.

According to Texas Southern University professor Robert Bullard, “The effect of NIMBY victories appears to have driven the unwanted facilities toward the more vulnerable groups. Black neighborhoods are especially vulnerable to the penetration of unwanted land uses — NIMBY-ism, like racism, creates and perpetuates privileges for [white people] at the expense of people of color.”

This occurs in Marin as the lowest-income, most densely populated and racially diverse community in the county, Marin City, contains the highest concentrations of low-income housing, with new developments planned. While the ongoing construction of affordable housing in Marin City fulfills the county’s state-mandated quotas, it also distances wealthier residents from affordable housing.

Consequently, Marin City must deal with the legitimate burdens of providing low-income housing as it strains underfunded public resources.

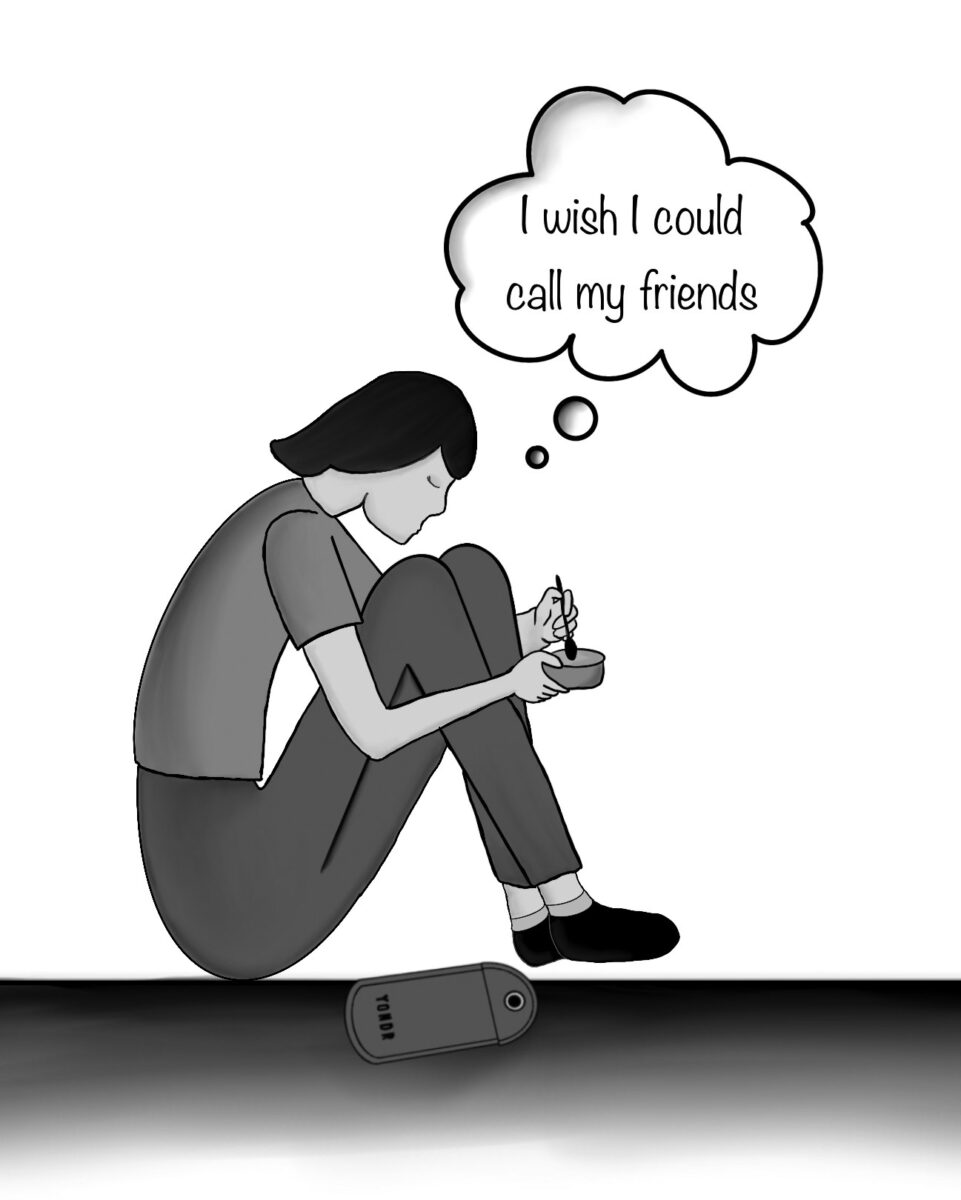

Not only does the discriminatory construction of affordable housing risk damaging diverse communities and evade the responsibility of wealthier ones, but it also hurts those who work in them. For hourly wage earners, with Marin’s rent costs tied for the most expensive in the U.S., the prospect of living close to their workplaces is often impossible.

Even for Marin teachers and other school employees, these prices exclude nearly 43 percent from renting an average studio apartment where they work. While the obvious remedy is expanded local affordable housing, NIMBY-ism ignores this.

Beyond helping those who teach in Marin, low-income housing also benefits students. A 2019 review of classroom integration concluded that greater socioeconomic diversity “can help reduce bias and counter stereotypes” and “promote more equitable access to resources.” This translates to low-income students benefiting from learning in Marin’s classrooms while their peers simultaneously gain access to new perspectives.

Marin has the ability to promote this with low-income housing, while also helping teachers and others who work in the county. However, efforts to redirect this affordable housing elsewhere defeat its purpose.

If Marin residents truly support social welfare programs as the liberals most claim to be, then they must genuinely support affordable housing. And while the addition of any new housing poses inherent challenges, these should not push residents away from supporting ethical developments — least of all should they motivate current residents to force housing upon other communities.