Publicly Funded Housing in Marin: Supported Until it Strikes Home

December 13, 2021

As we emerge from the pandemic, plans to construct a publicly funded housing complex in Mill Valley have been reintroduced by city planners. The proposal involves a 40-unit housing development that aims to address the city’s lack of diversity in the real estate market by making more affordable homes.

According to Zillow, the Mill Valley median home price has risen from $960,000 to $1,930,000 in the past 10 years. Marin’s notoriety as an expensive county to live in has only been exacerbated in the past decade, and the issue is currently being addressed across city halls.

“It’s very hard to afford housing right now, especially in California, especially in the Bay Area, and especially in Marin,” Patrick Streeter, the Planning and Building Director for the Town of Ross, said.

Streeter says the solution to high housing prices is state-allocated construction units. Distributed amongst all Bay Area jurisdictions, about 400,000 units have been assigned.

“[The State Department of Housing and Community Development] determines what the need is for housing across the state, and then local governments distribute that amongst themselves,” Streeter said. “We’re responsible for showing that we can accommodate those units.”

Each district submits their accommodation demonstrations in order to satisfy the unit requirements, but few are actually constructed. Even though it

is not mandatory to fulfill this plan, Mill Valley is taking steps past just a report of potential housing. Danielle Staude, a Senior Planner for the City of Mill Valley, considers the construction process very extensive.

“In March 2020, the city council approved the housing advisory committee’s work plan and there were several priorities,” Staude said. “The priorities included identifying a publicly owned site that the city could look at building affordable housing on or selling the land to leverage funds to build affordable housing elsewhere. We can actively make a diffe

rence by utilizing our land.”

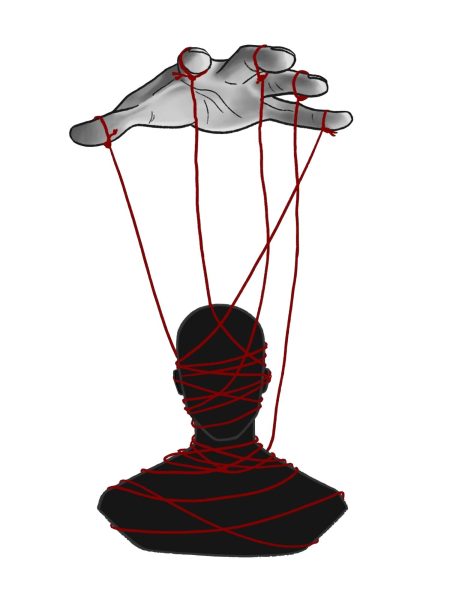

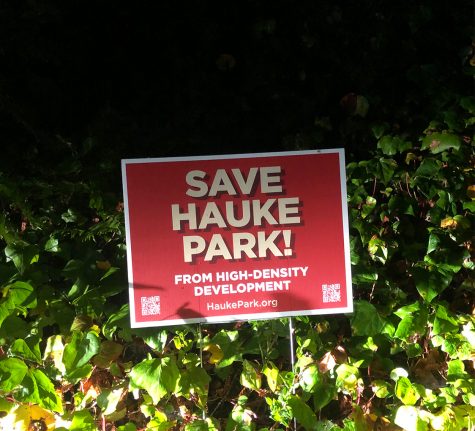

However, the plan has been met with a strong community reaction. Mill Valley residents voiced their opposition to the proposal on public forums, email chains and in an organized group called “Friends of Hauke Park.” The name “Hauke Park” refers to the neighborhood surrounding the collective playground, public fields and paths in Mill Valley.

Charlotte Casey, a Redwood senior and resident of the Hauke Park neighborhood recalls the neighborhood discussion in the earliest stages of the project.

“A lot of people were very vocal at the beginning. I wasn’t really shocked by the reaction. The thing is, they say it’s low income, but the people that are going to be moving in are people that already work here, they just can’t afford a crazy expensive house,” Casey said. “It was kind of ironic that it was around the [Black Lives Matter] movement when everyone was talking about equality and equity because we’re all for it in Mill Valley, unless it’s in our backyard.”

Not only is housing in Mill Valley not feasible for a range of incomes, longtime residents have an increasingly difficult

time affording homes. The range of incomes of residents that can afford a home in the Bay Area consistently narrows with time, excluding generations that have been in the area for decades.

“It’s very hard to afford housing across California, especially in the Bay Area and Marin. The median house price has gone up steadily, and it hasn’t been matched by construction of housing,” Streeter said.

This plan clearly demonstrates that Mill Valley has attempted to create more equitable housing and that the need for equitable housing grows as the prices of housing do as well.

“I am definitely in support of it. We need way more affordable housing. … The key workers in Marin can’t even afford to live where they work. That’s wrong, and we need to make Marin a lot more inclusive,” Casey said. “There needs to be equality everywhere and that starts in your hometown.”

Casey is not alone in her assertion that the workers of Marin should have the option of localization. Streeter recognizes the many benefits of this project for the community as a whole, as well as the individual.

“There’s a lot of people that work in Marin, but can’t afford to live in Marin. So they’re commuting from the South Bay, so an increase in greenhouse gases, and an increase in their own personal costs of paying tolls and gas. Being able to live where you work is a huge benefit, environmentally and fiscally,” Streeter said.