Why cancelling the requirement of standardized tests is not the solution to a biased system

By Mia Kessinger

Founded in 1926, the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) has been in place for nearly a century. This and the American College Test (ACT), are typically required in college applications in order to provide an objective way of comparing each student. However, with the recent coronavirus outbreak, many schools have decided to drop this requirement and become test-optional for the class of 2021. While this change may be viewed as a new chance for students who have high GPAs to be accepted into higher-ranked colleges, going test-optional will ultimately make it more difficult to get into schools because students’ test scores usually provide a more diverse and complete application.

It is hard to deny that standardized tests are flawed, but their benefits outweigh their negatives in the long run. Research conducted by the ACT has found that strong scores are predictive of success in college and in the workforce. The data found “ACT composite scores to be effective for predicting long-term success at both four- and two-year institutions, citing evidence such as higher college GPAs and graduation rates for students with higher ACT scores.” Other research by the ACT established that high school students with the same GPAs often had varying test scores—proving that test-optional schools would assess all students with the same GPA as having the same chance of being successful in college when that is not the case at all.

Furthermore, the main criticism of standardized tests is that they put underprivileged families at a disadvantage because the tests favor affluent families who have the means to study with an expensive private tutor. In reality, if test requirements were to be suspended forever, students would only be judged from their GPAs, where the prejudices would be very similar, if not the same. According to a study conducted by Inside Higher Ed, half of high school students in the United States graduate with an A- average. So where would that place students who can’t afford to go to a private school or can’t live in an area with a strong public school system? At the bottom.

Students who attend struggling public schools in low-income areas and receive good grades can easily be disregarded by universities when compared to other students who come from superior schools that offer tougher curricula. For example, a student at a wealthier school that has Advanced Placement (AP) and honors classes might have a higher GPA than a student who attends a poor school that doesn’t. In the eyes of a college admissions officer, the student who has a higher GPA might look more attractive even though the student who comes from a weaker school with an A average could be just as smart. Thus, without the ACT or SAT, poorer students will be facing close to the same biases they would be with the standardized test requirement.

Nonetheless, if the SAT is continued to be required, there needs to be a push for more free tutoring resources so that the inequalities between socioeconomic classes are reduced. Some complimentary options for less affluent students, like Khan Academy, already exist. Supplements like this have been proven to be helpful; in an interview with the Harvard Gazette in March of 2014, Harvard Dean of Admissions William Fitzsimmons stated that,“The free test prep provided by the College Board and Khan Academy will help level the playing field for students from middle-income and most economic backgrounds.”

In addition to these resources, according to College Board CEO David Coleman, a tool called “Landscape” was recently implemented which provides admissions counselors with “information about a student’s background, like average neighborhood income and crime rates.” Because this allows colleges and universities to view a student’s score objectively in the context of the conditions in which they live and learn, it helps reduce the unfairness in SAT scores. With improvements like these, there is no reason why the requirement to submit them should be waived.

While it might be a difficult task, it is imperative that the College Board find ways to connect with more tutoring companies, such as the Princeton Review, to create other free online study resources to make the SAT and ACT more equitable tests of students’ academic and intellectual ability. Even without these changes, however, the SAT and ACT must stay in place because they provide a more diverse and objective way of looking at a student.

The poor standards of the standardized testing system

By Martha Fishburne

Standardized testing is fully ingrained in the fabric of our high school culture, almost as much as getting a driver’s license, going to prom or cringing at old photos from middle school. It’s a rite of passage: studying with tutors for hours and taking practice test after practice test. But as colleges across the country suspend their standardized testing requirements due to the coronavirus, tired students must ask the question: is standardized testing necessary in a post-coronavirus world?

Not really.

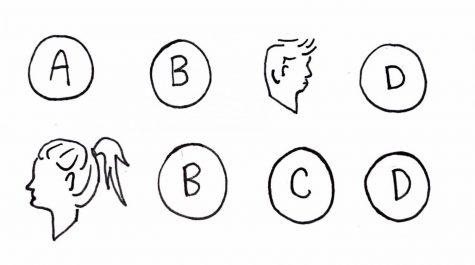

Before coronavirus, test-optional schools were primarily private liberal arts colleges, including Bard College, Brandeis University and Pitzer College. The coronavirus pandemic, however, has pushed other well-known colleges, including four Ivy League schools, to make the transition as well for the Class of 2021. That, and the recent vote among the University of California schools to waive American College Testing (ACT) and Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) requirements until 2023, just goes to show that these requirements are not necessary to determine a student’s academic capability. In fact, a study headed by William Hiss, a former dean of admissions at Bates College, found that those who submitted test scores only had a 0.05 percent of a GPA point higher in college and a 0.6 percent higher graduation rate. While the SAT and ACT can gauge a student’s intelligence to a certain extent, it primarily tests a student’s strength as a test-taker.

On top of being poor indicators of a student’s academic credentials, SATs and ACTs are biased against students from lower socioeconomic classes. For example, a study conducted by Inside Higher Ed found that the average score on the English section of the SAT was 433 for participants whose family income was less than $200,000, while those whose family income was $200,000 or more scored an average of 570.

Such polarizing score discrepancies can be partially attributed to the high cost of the tests and their preparation. According to the College Board website, the SAT with an essay portion costs $64.50. While the website also states that they can waive the fees if needed, that does not release students from the obligation of having to pay for test prep which, as reported by a 2020 Bark article, can cost around $150-$220 an hour in Marin. Considering most students have a separate tutor for the math and English sections and meet with each tutor an average of 5-8 times, preparing for the SAT and ACT can easily cost thousands of dollars, which many families cannot afford.

Although organizations such as Khan Academy do offer free or reduced-price tutoring virtually, online tutoring is a poor substitute for a private tutor due to the lack of personalization and human interaction. A report published by the ACT website states that preparing for the ACT with a tutor improved student scores, whereas using alternative methods of preparation had no notable effect on them. ACT and SAT advocates claim that the tests are ways to pick underprivileged teens from their poor high schools, but the economic barriers that come with taking these tests do little to help those from impoverished backgrounds.

It is true that the SAT and ACT allow college admissions offices to objectively compare students from different high schools by having them all take the same test, but until all students are given equal preparation and educational opportunities, the SAT and ACT will never truly be objective. I personally test well, and including my ACT scores in my application would give my application a boost. I am not writing this as a bitter test-taker, angry at not reaching her target score, but rather as someone who does not want the acceptance into my dream school to come at the expense of other qualified students who are at a disadvantage.

Another argument presented by supporters of the ACT and SAT is that, without relying on standardized testing, colleges would have to place more emphasis on high school grades during the college acceptance process. At the surface level, comparing students’ GPAs from vastly different high schools is virtually impossible; while grades can be evaluated in the context of the high school, they can not be a measuring stick for colleges to judge applicants. America’s unequal educational system means that it is possible for admissions offices to disregard a high GPA from a lower-income school, harming those students in the same way that the ACT and SAT would.

To combat this, College Board created an adversity score, which judged students on a 1-100 scale regarding their environment, factoring in school quality, neighborhood crime rate and poverty level, among other things. However, College Board rejected the metric only a few months later after facing backlash from parents and students alike, implementing instead a similar tool called “Landscape” soon after. Although College Board is trying to make the ACT and SAT a fair system, it is not enough to merely compress the lived hardships of disadvantaged students into a 1-100 scale, and attempting to do so only brings discontent from wealthy families who feel slighted.

It’s true: as of now, there is no perfect solution. Many of the problems with the SAT and ACT are societal problems, not just problems within College Board, further complicating the issue. But rather than relying on an outdated test that tries to distill multi-faceted people into a number, college admissions offices should put more stock into other aspects than grades and standardized testing scores, such as essays and letters of recommendation. And until another idea can be implemented, it is unfair to put marginalized students and their futures at stake.