“Trump administration seeks to deport children with life-threatening illnesses.”

“Newest immigration changes under Trump spark confusion.”

These are just a few of the most recent headlines in the constant debate and coverage on immigration in America. Countless sources ruminate on the ethics and facts behind deportation, as well as its effect on America and the general population. However, many fail to realize the impact deportation has on the countries receiving these deportees.

According to the Washington Post, in 2018, over 57 percent of deported individuals were convicted criminals. These often dangerous criminals are shipped back to their country of origin, where they continue to cause trouble. In fact, for every 10 convicts a country receives per 100,000 people, the murder rate in that country goes up by two, according to the Washington Post. This is especially true when those criminals are gang members, as deportation over time helps to spread the reach of gangs.

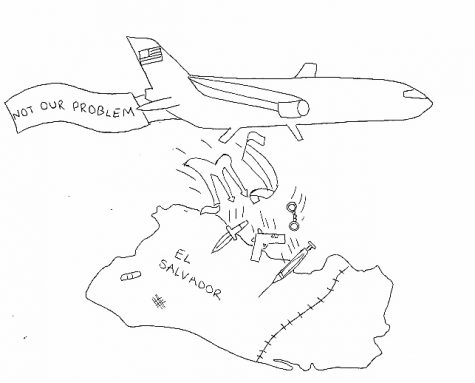

One example of the damage caused by the deportation of gang members is the gang La Mara Salvatrucha (M.S. 13). In the 1980s, El Salvadorans who fled to America in hopes of escaping civil war in their home country began to form a gang in Southern California for their own safety. Over the next decade, this gang grew and developed into M.S. 13. El Salvador finally signed peace accords in the 1990s, but the United States simultaneously deported almost 4,000 members of M.S. 13 back to their country. Instead of mitigating the gangs, this action led to members establishing factions throughout El Salvador and the neighboring countries of Guatemala and Honduras, known as the “Northern Triangle.” In fact, in 2012, the Department of Treasury classified M.S. 13 as a transnational criminal organization. Essentially, the deportation of gang members allowed M.S. 13 to establish an organized crime association, which would cause problems still present today. The Northern Triangle rates among the most violent places not at war largely due to gang violence, according to Insight Crime, which studies threats to the security of Latin America. Though no one could have predicted the drastic effect at the time, America must not repeat this mistake in today’s world.

The Trump administration continues to promote Immigration and Customs Enforcement (I.C.E.) raids, such as the recent ones in Mississippi. I.C.E. officials have also been posted in areas of Marin with high Latino and Hispanic populations, such as San Rafael. As this occurs, it is important to consider that, like the removal of M.S. 13 members, if handled improperly, it could trigger the international spread of dangerous and organized gangs. In 2017, the Enforcement and Removal Operations of I.C.E. removed over twice as many suspected or confirmed gang members than the previous year, according to the Department of Homeland Security. Though many do not want these people free in America, gang members should be properly detained somewhere instead of being set loose where unstable governments and economies are unable to curb gang violence. Resources should instead be funneled into preventing young men and women from joining gangs in America, especially in neighborhoods where gang activity is concentrated, as they are at a higher risk. There are many factors throughout all aspects of life, including home and social settings, that can affect one’s likelihood to join a gang. By educating youth on the dangers of gangs and providing alternatives for their future, it is possible to lower their risk of joining a gang.

While the ultimate goal is to decrease the number of illegal immigrants in America, the deportation of gang members in large groups does just the opposite. As gang violence continues to rise in El Salvador and its neighboring countries, more and more people come to the United States seeking refuge. According to the Migration Policy Institute, the total number of immigrants in the United States from Central America has doubled since 2000, and the number continues to grow. This is largely due to the increase of crime, especially in the Northern Triangle, which is closely tied to the control that gangs have over the general population.

Deporting gang members does not stop or even lessen violence. Rather, it allows crime to thrive elsewhere. When removing these people from our home, we must remember that we are sending them directly to someone else’s. Instead of claiming that it is “not our problem,” we should face the problem of gangs in our country head-on to benefit future generations not only in America, but internationally.