Throughout modern history, new and innovative forms of technology have been implemented in people’s daily lives and workplaces. Whether it be the printing press in 1440, the automobile in 1885 or the smartphone in 1992, technological pioneers are constantly introducing different ways of making human lives more efficient. After the early 2000’s tech boom, engineers and computer scientists have figured out how to push the societal boundaries with the introduction of artificial intelligence (AI)—except this time, the implications could be potentially debilitating to our economy and social stability.

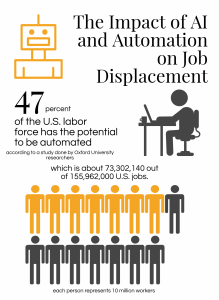

According to Stanford professor John McCarthy, AI is a form of technology that uses the concept of machine-learning (learning from data, environmental conditions or direct teaching) to create intelligent systems in robots or other forms of mechanization. Through their comprehensive global survey, Pew Research reported that 72 percent of Americans are concerned that the rise of robotics and AI will displace human jobs and lead to severe economic issues.

According to The New York Times, pre-existing technology has the capability to automate 45 percent of paying jobs. Researchers, business owners and workers alike often debate about whether the effects of incoming AI will be positive or not. On one hand, AI and increasing automation show significant promise in raising efficiency and maximizing company profits, which could benefit our economy. On the other hand, the displacement of workers via machinery or robotics is daunting to those with jobs that could easily be automated such as cashiers, truck, taxi and uber drivers or fast food cooks.

AP Economics teacher Ann Tepovich believes that one of the potential encouraging features of AI and automation could be allowing people to enhance their human capital.

“It makes us more efficient. It frees labor up to theoretically gain different kinds of skills and add [to society] in different ways. If you can be replaced by a robot, theoretically, that’s not a good use of human labor,” Tepovich said. “Maybe what we should be doing is training people to do other types of jobs that can’t be replaced by robotics so it makes for people using their skills in different ways—enhancing their own ‘human capital,’ which in economics is your skills, your brains, your know-how—to be using that in a different way that adds more to the economy and to prosperity.”

In a 2016 article, the Harvard Business Review expanded on this increase in efficiency, saying that throughout the 1990s and 2000s, productivity growth increased by .35 percent yearly due to robotics. With said prosperity and efficiency, though, comes substantial issues for lower-income individuals. According to National Public Radio (NPR), automation and robotics could displace 400-800 million workers by 2030.

Senior Austin Patel, who has interned at the Buck Institute, an independent biomedical research organization, for seven weeks, thinks of AI and automation in a more positive light. He himself has created AI programs such as the program he developed his sophomore year for an Honors Integrated Science project that could decipher handwritten letters and replicate them. Through his personal experience, he doubts that AI will have the impact that many speculate.

“It’s pretty hard to get an AI program to actually accomplish what you want it to do. I guess that makes me think, ‘No, it’s not going to take over the world.’ Yes, it might displace workers in certain fields, but I think it opens up more opportunities as well,” Patel said. There are just tasks that are better done by computers than humans … and there are some tasks that humans do better than robots.”

However, AP Economics teacher Paul Ippolito finds that, on the contrary, worker displacement is a reality that must be acknowledged, and it comes as a result of an economic concept called disruption.

“Disruption is really a process of destroying an old industry and inventing a new, hopefully more efficient way of doing it. People are going to find their skills are no longer relevant … they’re going to have to go back to school and get new skills that are relevant,” Ippolito said.

Tepovich questions where the money will come from to pay for said education, and how people will find the motivation to follow through with learning unfamiliar skills.

“I think it takes a lot of investment. If you’re saying to somebody you no longer have a job and we want you to go back to school to learn or go through retraining, how do they pay their bills? Where that financial investment comes from, is it the government, is it the companies that are looking for workers, is part of the dilemma,” Tepovich said.

This reality not only has implications for those who are older and are currently being displaced, but also the youth that will soon be entering the labor market. Many wonder how the introduction of AI and automation into the workforce will impact this younger generation.

“It means that it’s harder to get your foot in the door and start your career. If you’re a valuable employee, a good company will never let you go. It’s really about getting those internships in college,” Ippolito said. “I think the main thing is to receive a lot of education and get out there in the real world. You can always pick the company you work for, but the first company you work for may determine what you end up [pursuing].”