Since their creation 45 years ago, mobile phones have become arguably the most influential source of communication and information. People rely heavily on their devices to text friends, call relatives, store information or keep up to date on news and social media. Americans, on average, check their phones 80 times a day, according to a study by global tech protection and support company, Asurion. Our generation utilizes these devices all the time, yet few have a clue of what really goes on inside them. A couple of recent incidents, the Meltdown and Spectre security bugs and how Apple handled their degrading iPhone batteries, have raised awareness of the issue of tech transparency and whether society can truly rely on the companies that make these products to keep their customers secure and informed.

Meltdown and Spectre are two major central processing unit (CPU) security bugs that have recently affected technological devices such as iPhones and tablets. The bugs utilize critical vulnerabilities in modern processors and allow programs to steal data located on the computer, ultimately corrupting these systems to bypass and access information stored in the memory of other running programs, including passwords, emails and personal documents.

Three major chip producers are the key players in the issue created by these two malicious security defects: Intel, Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) and ARM Holdings. Although the bugs only surfaced last December, Meltdown and Spectre affect personal computers and mobile devices made within the last 20 years. Additionally, the cloud is also affected, which may make it possible for attackers to steal data from other customers in the system.

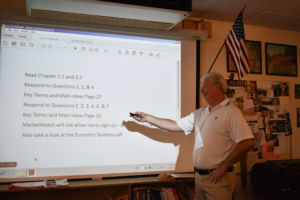

Even though Intel has known about Meltdown and Spectre since June 2017, they did not inform the public until rumors broke in January 2018. Computer graphics, economics and government teacher William Crabtree believes that this lack of communication and transparency is not acceptable. He argues that companies should take ownership of their actions.

“That’s irresponsible—corporate irresponsibility. Essentially, it’s a financial issue, they don’t want to take the hit financially and they don’t want to take the hit [public relations] wise,” Crabtree said. “It’s like every big organization or bureaucracy doesn’t really want to face the music, so they practice this standard operating procedure of plausible deniability until it becomes too much to deny.”

However, WARZAC Technologies Co-CEO, University High School senior and former Redwood student Warren Niles feels that Intel handled the timing of its announcement in a reasonable manner, since they needed to create an optimal solution first.

“If they had explained and released all that information about what Spectre is and what Meltdown is without any solutions, you could have had people’s financials stolen. I understand companies need to balance a level of transparency along with consumer safety but in this case, I think it’s okay that they released it later given that after this came out, there were already some patches available,” Niles said.

Given his concern with tech security, Niles created WARZAC Technologies along with Redwood senior Zach Walravens to develop encryption software that ensures the security of information being sent over the internet, as well as the protection of stored information through database software.

Both Meltdown and Spectre relate to how the CPU executes commands. They exploit speculative execution, which is a technique used by chips to increase performance by guessing likely future execution paths and prematurely executing the instructions in them. According to Niles, when a computer needs to access a piece of the user’s information, it communicates directly with memory on how to retrieve it. By using this process to their advantage, Meltdown and Spectre are able to steal data by manipulating the CPU to give it exactly what it wants, such as private pictures and information.

“What it will do instead is say ‘90 percent of the time this is true,’ so I’m going to speculate that this ‘if statement’ is true and execute all the commands below it. And some of those commands may include leaking private information,” Niles said.

Spectre involves exploiting branch prediction, which is predicting which of two branches is most likely to be correct and then starting to execute it before it knows which is the intended path. In simpler terms, it’s like a camping group going on a hike in the woods, a hike that they have been on multiple times. They bring a GPS to help navigate, since there are many different paths. When they arrive at one of the complicating forks, the GPS stops working. Since they are in a hurry, they don’t bother to wait for the GPS to recalibrate and choose a path based on past experience.

Niles provides an example of how Spectre breaks down the isolation between different applications and tricks programs into leaking secret information.

“Let’s say you have your bank opened up in another tab. Spectre could break down that wall between your two separate tabs and take your bank information from the filled-in fields that you have. It can steal cookies, which can contain tracking information. Anything you have stored on your computer can be attacked by these methods,” Niles said.

Meltdown exploits out-of-order execution to leak memory, which allows instructions further down the chain to be executed at the same time as, or even before, preceding instructions. Hackers take advantage of the way computers process commands to request information be sent to them ahead of the authorization conducted by the CPU. With this, they can essentially trick the computer to send them private content.

The irresponsibility that Crabtree speaks of is evident, as Intel’s initial response to the issue denied any allegations claiming that their devices were insecure and unreliable. They also refuted claims that the problem was unique to Intel products, citing that multiple types of computing devices are susceptible to these exploits. Despite reports that the patch needed to fix Meltdown could slow down computers by as much as 30 percent, the company claimed any performance impacts that resulted from the installation would not be significant.

Following this denial, Intel released a second response a day later indicating that the performance impact from the software updates may initially be higher but not offering many details on how the impact could be mitigated. In the third statement, Intel acknowledged that the impact may be significant in some cases.

The severity of the current issue is multiplied by the fact that while there are patches to mitigate Meltdown, there is no easy fix for Spectre.

“That’s why [researchers] chose a ghost [as the logo] for Spectre because they assume that it’s going to be around for much longer versus Meltdown, which you can patch with software,” Niles said.

In relation to the Meltdown patch slowing down computers significantly, Crabtree recognizes that this side effect has to be accepted.

“It’s like the gift that keeps on giving. You don’t have any say. You’re on the train and the train just got slow. So if you want to buy all new devices once they come out with different hardware, which remains to be seen how long that’s going to take, you could do that. But until then, there’s nothing you can do about it,” Crabtree said.

In regards to transparency, Crabtree believes there is a fine line that has been crossed. However, he acknowledges that people will still continue to depend on these companies.

“There is a certain level of trust that has been breached with regard to being able to trust Intel, being able to trust AMD and any other chipmaker involved in the future. But we will, won’t we? It’s almost like we’re not going to stop using the devices,” Crabtree said.

Walravens shares a similar view regarding our growing reliance on tech devices, emphasizing the responsibility companies need to maintain.

“As these pieces of technology become more and more important to people’s lives, these companies have a greater and greater responsibility to make sure they are secure,” Walravens said.

Additionally, he fears the increasing lack of security, especially in the time to come.

“I feel like nothing’s really secure nowadays. There are just so many opportunities for attacks—more and more of them just keep coming in the foreseeable future,” Walravens said.

Despite the bugs’ broad reach, Meltdown and Spectre have fortunately had little impact at Redwood, according to IT Systems Specialist Les Gill.

“Nothing [has happened regarding the bugs] so far, but we did get warnings about some systems that we do have on campus, some older ones. I don’t have a percentage but it’s minor, very small—old systems that are still in use but not a big threat,” Gill said.

However, Gill does expect this incident to push tech companies to be more transparent with customers about issues with their products.

“Especially if we’re like the whole campus just using Dell—this is our preferred device of use, we would definitely like to know if there are any issues. We don’t want to be taken advantage of. We’re spending all this money and you’re not being up front with us. We are relying on you for this great technology and we are telling our students, our staff that this is great technology and it’s full of bugs,” Gill said.

The second overarching incident is one that hits closer to home for Redwood students—the lack of honesty from the Apple dilemna identified in early December 2017 regarding phone batteries. Instead of telling customers about degrading batteries, Apple chose to slow down iPhones to compensate for battery life issues. Users ended up replacing their phones when they could have just replaced their batteries for $79.

Walravens sees this move as manipulative and unfair, especially since people are so dependent on their phones.

“I feel it’s a real ‘not nice move’ to let there be some huge issue in a device people rely on so heavily and not tell them about it. Apple is just abusing the fact that people rely on their products so much,” Walravens said.

Crabtree highlights how it all boils down to the economic side of the business, correlating the company’s move to a money grab.

“They’re all in the business of getting you to come back to the well. They’re all wanting you to upgrade and further spend money on this product because that’s their livelihood,” Crabtree said. “It’s no surprise to me that the batteries all of a sudden kind of tank. And then there was never any kind of messaging that said ‘Oh, just replace the batteries and it will be all good.’ No, they want you to buy that iPhone X or whatever they’ve got going on now.”

Apple eventually acknowledged they were wrong and sent an apology letter to their customers on Dec. 28, offering discounted battery replacements for $29 for a year. On Jan. 24, 2018, Apple announced that it is planning to add a software update called iOS 11.3 that will allow users to opt out of Apple slowing down their iPhones and a tool that shows their iPhone’s battery health.

Despite this apology, the U.S. Department of Justice, as well as the Securities and Exchange Commission, will be conducting an investigation to determine if Apple’s unveiling of the software which slowed old models infringes upon security laws.

As a result of these situations, tech transparency has been thrust into the spotlight. Our reliance on these devices has manifested into an issue that allows large corporations to hold back information in favor of economic growth. Similar to the Spectre bug, this problem continues to linger and will remain for a long time with no feasible solution in sight.