Unlike the typical hour-long session on a psychologist’s couch, wilderness therapy is a ground-breaking mode of treatment that fits our time and our Redwood community.

“I was picked up in the middle of the night by private escorts,” anonymous Redwood alumni “John” said while recounting his forty-five day experience in Muir Woods Therapy.

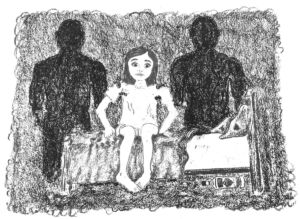

These alternative forms of therapy, either wilderness or impound, use fear to forcibly push students out of their comfort zones. Wilderness therapy helps adolescents overcome emotional, adjustment, addiction, and psychological problems outdoors, while impound therapy is in a group home. There are designated men, typically referred to as “Big Mikes,” that transport adolescents to the different therapy locations, often in the middle of the night.

Redwood alumna Lennon Lott, who spent 35 days in the wilderness therapy program, Suws, when she was only 12 years old, explained the experiences she had with the “Big Mike” tactic in her therapy group. Lott attended Suws Wilderness Program, as it was the only wilderness program that would take her at such a young age.

“A lot of the girls at Suws were picked up by Big Mike. He comes into your room at three in the morning and scoops you out of bed kicking and screaming with his other big buddies, and takes you to the airport. “Big Mike” sits next to you on the plane until you’re there,” Lott said.

There are a multitude of reasons that teens are sent to therapy, including behavioral issues and substance abuse.

According to the Wilderness Research Center in Idaho, adolescents in the United States are at a much higher risk of addiction, behavioral issues and instability than previous generations due to evolving cultural influences and modernizing technology. These influences include, among others: social media, print media manipulation through images, advertisements, and more relaxed attitudes towards drugs (e.g., the legalization of marijuana in many U.S. states).

Adolescents are most commonly sent to wilderness therapy because of behavioral issues or substance abuse, and Marin teenagers seem to be specifically more susceptible to these factors. Data from Francine D. Ward has shown that Marin has one of the highest teenage binge drinking rates across the United States. Marin County has also received an F grade from the American Lung Association for overall tobacco issues in both teenagers and adults, revealing the prevalence that drugs and alcohol has on the adolescent community.

Wilderness therapy can serve as a forgiving environment, providing support to adolescents in need of rehabilitation.

“I was surrounded by a bunch of other kids with withdrawals which made the process easier as I was able to relate with them,” Bechard said.

Teens all over the country are experiencing similar situations, thus providing a supportive community for these adolescents.

There are over 38 therapeutic wilderness programs available in the United States for adolescents. Wilderness therapy has distanced itself from past stereotypes of being a “boot-camp” for adolescents. Instead, it has turned into a supportive environment for individuals to recover through nature. According to Open Sky Wilderness, this type of therapy is filled with employees who believe nature has the power to heal.

Wilderness therapy differs from the more mainstream services like outpatient and inpatient therapy, instead providing an outdoor alternative. Wilderness therapy helps adolescents heal, grow and learn through nature.

“I came back wanting to go out and do stuff, like go hiking, unlike before where I just wanted to sleep all day and not do anything. I was super lazy and didn’t like walking, even a block,” Lott said.

There are several different scenarios in which students have been taken to a traditional form of therapy, but Lott’s experience didn’t conform to the typical “Big Mike” tactic.

“My mom told me that I was going [to the Suws therapy program] and she bribed me with a nice camera and Lululemon pants when I got out,” Lott said. “She also said that it was going to be super fun, I was going to meet great people, and there was equiline therapy, so I was going to ride horses which I like to do.”

This transition from a privileged lifestyle in Marin County to living with a bare minimum forces students to adapt to an unwanted reality. They have to move to a new place, be surrounded with different people as well as make changes to their daily routines.

“I had packed a hair straightener, a cell phone, and all these clothes, and they took that all away and gave us one pair of wool pants, boots, three jackets, a pair of long-johns, underwear, and a beanie,” Lott said.

Adaption was unavoidable and forced these students to set aside their ego and accept the help provided. Redwood alumnus Berklee Bechard, another student who experienced the “Big Mike” tactic, described how he eventually had to give into the therapy despite how badly he wanted to leave.

“I was furious for the first five weeks, then it beat me and I followed through with the program,” Bechard said.

The responsibility that is placed on adolescents in wilderness therapy helps build a sense of community, reinforces that these students are not alone in their recovery and shows them the power they have to help others.

The experience doesn’t serve only as a way to help oneself, but also as a way to assist others that are struggling with similar issues. Lott provided support to a friend during therapy, which helped her gain a sense of responsibility throughout the program.

“Knowing that she relied on me was a big part, and being able to teach someone how to live out there was cool,” Lott said.

Although this type of therapy can be jarring and abrupt, it can provide these students with long-lasting positive takeaways that they can apply to their everyday lives.

“I had a stronger self of mind. You feel more centered and aware of who you are and what type of intentions you have and what your motivations are in the world,” John said.