Educational realities behind ADHD

by Daniela Schwartz

“In middle school I’d always be standing up in my classes and fidgeting with stuff and bending paper clips and flinging rubber bands, and doing whatever to just keep myself occupied. My teachers basically realized that they had to put me in the back of the classroom because I’d always be standing up,” said junior Aidan Rankin-Williams, who was diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD) in eighth grade.

According to a study by Medical University of South Carolina psychologist, Dr. Russell Barkley, ADHD is a disorder that affects roughly one to three students in a classroom of 30.

Despite the high rates of ADHD among children, diagnosing a child with the disorder can be a complex task due to the many different types of evaluations available. However, diagnosing has gained attention over the years. According to the National Survey of Children’s Health parent reports, 11 percent of children ages four through 17 have been diagnosed with ADHD. The same survey found that the rate of diagnosed ADHD has increased an average of about five percent per year from 2003 to 2011.

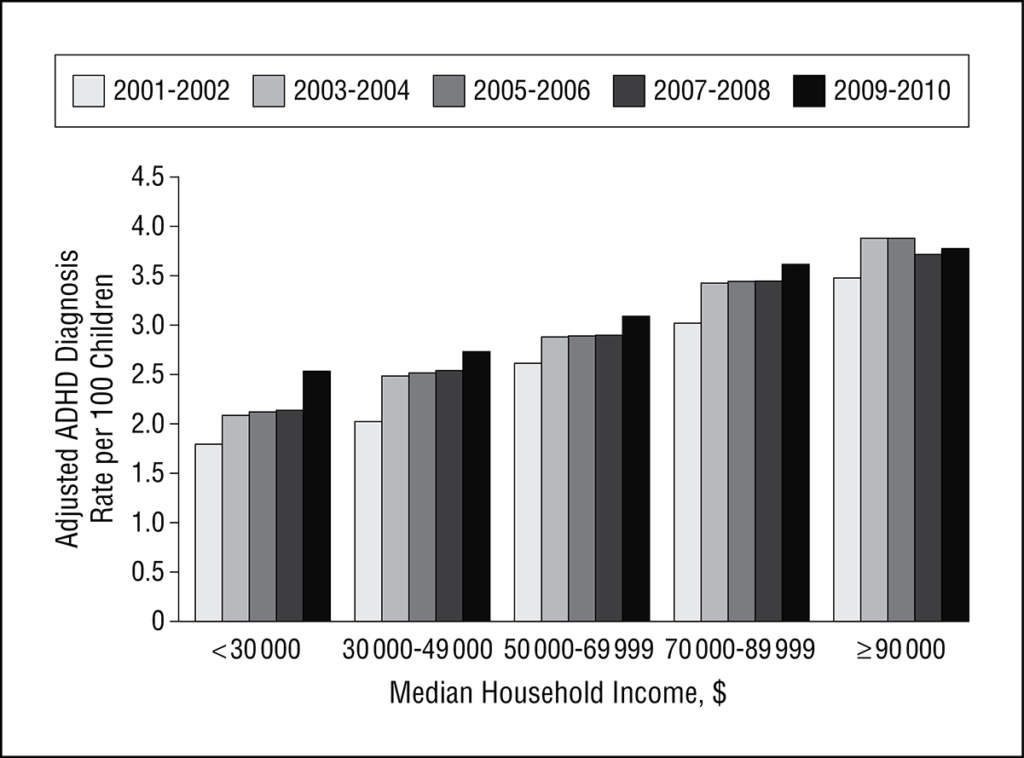

As ADHD attracts more attention each year, understanding the complexities behind the diagnosis has become critical. Both getting the diagnosis and receiving the appropriate benefits, like extra time for college entrance tests, can be challenging for students with ADHD. Additionally, ensuring that these two benefits are accessible for families and students of all income levels hasn’t been fully addressed. In fact, a report done by Jama Pediatrics, a medical journal published by the American Medical Association, showed that among all children with ADHD symptoms, poor children and children in minority groups are less likely to be diagnosed with the disorder. It also found that children from high-income families (classified as greater than $70,000 a year) were more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD.

ADHD Diagnosis

According to Kentfield based psychologist Merriam Saunders, diagnosing ADHD most commonly begins between kindergarten and third grade.

“Usually it will start with either a parent noticing there is something different about their child, maybe they have so much more energy and an inability to sit still, and often that comes into play when they first come to school—preschool maybe,” Saunders said.

Saunders said that if the parent doesn’t detect anything, then a teacher or school personnel may bring it up to them. Next, the family usually visits their pediatrician, who sends a questionnaire home with the family for both the parents and teachers to fill out.

“The doctor will get the questionnaire from the [home and school] and if they check off enough boxes then they’re able to diagnose the child with ADHD,” Saunders said.

This is the simplest way to get diagnosed with ADHD, but there are a number of other methods that range in cost. Junior Antonia Thomson was diagnosed with ADHD her sophomore year. She said she went to a psychologist who specialized in ADHD to receive her diagnosis, instead of going to her pediatrician, because she thought a specialist could give her a more thorough evaluation.

“My whole life I’ve been kind of spacey and can’t pay attention for a long period of time, but my parents just thought that was how I was. Then I think it was about two years ago I was diagnosed with it [ADHD] by a psychiatrist, and my parents kind of realized,” Thomson said.

Rankin-Williams also went outside of his primary care provider to take the Quotient ADHD test at a Kaiser Permanente facility in Oakland. During this test, the doctors used a headband-like gadget that monitored each time Rankin-Williams clicked the spacebar on a keyboard while watching a moving star on a computer to measure how well he could focus on a single object. He said that although this was an expensive test, his family wanted a better understanding of what the problem was before they spent the time to get him diagnosed.

Afterwards Rankin-Williams went to his doctor who gave him a much simpler evaluation involving blocks and memorization games. There, he received a diagnosis and prescription for ADHD medication.

According to Saunders, another way to tell if someone has ADHD is through a neuropsychologist report. The report consists of a multi-day testing assessment of the child using many Intelligent Quotient tests and various processing tests which pinpoint where in the brain the disorder occurs. Although this test is informative, it can cost anywhere from $2,000 to $5,000.

Although there are pricier tests, if a student goes to the doctor to get an evaluation their insurance should also cover the cost of medications, according to Saunders, as this would make it accessible to students of all socioeconomic backgrounds.

According to Andrew Sperling, the director of federal legislative advocacy for the National Alliance on Mental Illness, health plans are inconsistent with covering the costs of ADHD medication.

Since Rankin-Williams and Thomson were diagnosed at an older age, they didn’t need to have their teachers fill out a report for ADHD, a task that is usually necessary for elementary-aged children.

For most younger students, the gap between who is receiving ADHD diagnoses and who isn’t is dependent on whether their school can afford to respond to these students’ needs, according to Saunders.

“The more attentive the school, the more resources the school has, the more likely they are to single a child out as someone who is having difficulties,” Saunders said. “A school in a higher socioeconomic situation will have more resources and might notice a child struggling more. It might take a student with less resources longer to get diagnosed, but if it’s brought up and they have access to medical care then they should have the ability to be diagnosed.”

ADHD impact on standardized tests

Hearing students talk about receiving extra time on their standardized tests is common in the Redwood hallways. Over 70 percent of Redwood students self reported that they believe it’s fair for a peer with an official ADHD diagnosis to get extra time, according to a February Bark survey.

According to a national test prep and tutoring company called Applerouth, both College Board and ACT Inc. receive tens of thousands of requests from parents seeking extended time for their children to take standardized tests, which leads to the question of how these companies go about determining who receives the benefit of extra time.

Saunders said that expenses add up when a family is trying to receive extra time on a college entrance test.

“I would imagine it would be harder for a socioeconomically challenged student to prove to the college board that they need extra time because of all of the background information you need to prove to them,” Saunders said.

Even if a family can afford the costs, some are unwilling to pay, especially if their child has already been diagnosed.

For the past year, Thomson has been involved in the lengthy process to acquire extra time to take the SAT and ACT. She originally tried to request extra time on the SAT, but was denied twice.

“I sent all these letters, like a doctor’s letters, a letter from the school because I have accommodations, and from the psychiatrist who diagnosed me, and [College Board] kept saying not enough information, even though we had a ton of stuff,” Thomson said.

On the other hand, a friend of Thomson’s received extra time for her ACT after her first attempt to do so after submitting the results of her neuropsychological exam which proved that she has ADHD. The exam cost roughly $3,000.

“I guess the College Board takes that test more seriously or something; all my friend had to do was send her test results and she got the extra time right away,” Thomson said.

Thomson said that it was pointless to pay for an expensive exam, because it would tell her the same information that she already knows.

The College Board documentation for extra time also requires that a student show history of using extended time during high school tests, scores from timed and untimed academic tests, an occupational therapy evaluation and a teacher survey form.

“I think that if you show it through different evidence and multiple people and different sources then you should be able to get extra time, because it’s clearly flawed if I obviously have it and I can’t get extra time versus a classmate who gets it right away,” Thomson said.

Thomson is currently waiting to hear back from ACT, to see if she will be granted extra time on that test instead. Rankin-Williams decided not to go through the process of requesting extra time on either of the college entrance tests.

“I’ve wanted to get extra time for the ACT that’s coming up, but because I haven’t used extra time in my school tests, I can’t use it for the ACT” Rankin-Williams said. “I didn’t feel like it was worth it to go through the long process.”