By Annie Forsman and Adam Kreitzman

A Daunting Dilemma

Redwood alumnus Matthew Lewin lay silently as paralysis overcame him. Incapacitated, he waited helplessly as an emergency room doctor applied Neostigmine, in the form of a nasal spray, to reverse the paralysis.

Lewin had just been a guinea pig in his own experiment, one aimed toward the development of a successful antidote for snake venom. He took Mivacurium, a paralyzing agent, to simulate the effects of a cobra bite. Lewin has spent countless hours trying to fix a problem that is pervasive throughout the world: death by snakebite.

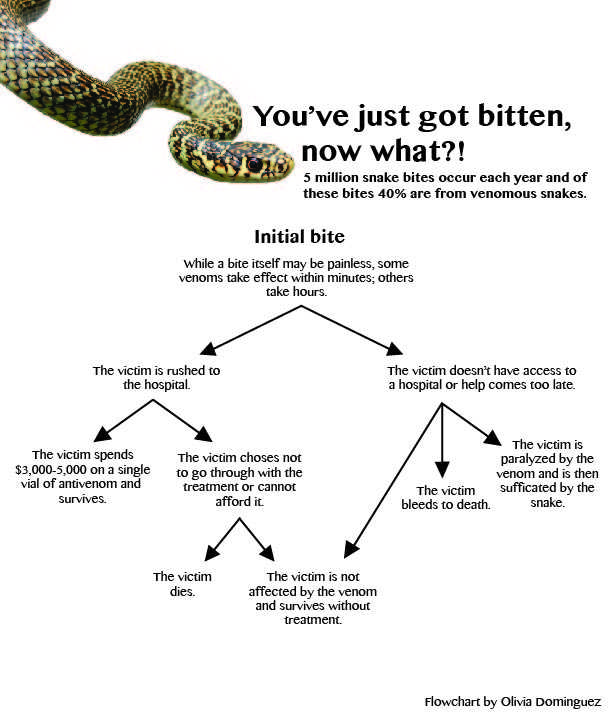

Victims of snake bites can die from an array of causes: Some venoms weaken the body, often causing paralysis, until the person suffocates to death. Others cause the victim to bleed to death. Often, bites are painless –– some people wake up paralyzed a day later because of a delayed reaction from a snakebite.

Snake attacks are prevalent across the world, and about five million people are bitten by snakes each year. Of those bitten, nearly 100,000 people die, and approximately 400,000 people are permanently disabled or disfigured, with many requiring amputations.

Lewin, an emergency medicine doctor at Kaiser Terra Linda and an expedition doctor for the California Academy of Sciences, is developing a cheap, durable treatment option.

Though snake-related deaths pose an enormous obstacle to many developing nations, Lewin believes they haven’t received enough attention.

“The pharmaceutical industry in general has completely abandoned anything to do with snake bites. The [Bill and Melinda] Gates Foundation, World Health Organization, and Unicef have invested, I think zero dollars into snakebite [research],” Lewin said. “It’s basically a problem that has been completely neglected.”

Due to this lack of recognition and support from large organizations, the development of an inexpensive, preventative, and on-site treatment has been delayed for almost a century.

While the 2014 Ebola epidemic killed 11,136 people, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, snake bites kill approximately 100,000 people per year. Lewin expressed concern that the Ebola outbreak received significantly more international coverage and attention.

According to Lewin, the number of people who will die from snake bites in one month during a monsoon is greater than the number of people who died in the entire Ebola epidemic. He believes that the reason Ebola received more media attention is because it was an infectious, life threatening disease that could spread, whereas snake bites are a problem of poverty that cannot spread.

“Even during the Ebola outbreak in Africa, hospitals were much more concerned with victims of snakebite,” Lewin said. “It is a pretty big problem that hasn’t been addressed.”

Lewin said that while lethal snake attacks are more of a foreign issue than a domestic issue, the dilemma is widespread, especially in countries such as India, whose population is approaching 1.3 billion.

“So many people don’t have indoor plumbing, so the risk of being bitten by a snake is high,” Lewin said. “When people are walking in flip flops outside every single day, the odds that they will be bitten by a snake are very high.”

Lewin said that those who live in the United States are incredibly fortunate because they do not have to worry about venomous snakes frequently slithering into their homes, gardens, or fields.

An Emerging Solution

When it comes to a snake’s bite, the key to survival is quick treatment. Those who are treated quickly after being bitten have a very high chance of survival. Often, those who get bitten suffer from some form of paralysis, and even if they are able to make it to the hospital, a massive economic decision awaits them.

Treatment for a snake’s bite is incredibly costly, especially for poverty-stricken people who live in developing countries or rural areas.

In addition, there is no definite way to know if a snake’s bite is fatal because venom can take effect ranging from a couple of minutes to an entire day, forcing people to gamble with their lives, said Lewin.

“Imagine being bitten, and, like most bites, it isn’t deep so you aren’t sure that [the snake] injected venom, and you won’t know for about four hours,” Lewin said. “Now you have to make a life-or-death decision of whether or not to undergo anti-venom treatment. And if you do, right there, that is six months’ income. Just the decision to get treated is a potentially life-altering event.”

Lewin said that many unnecessary fatalities come from people’s hesitation to get the necessary treatment.

“If you are poor and only one in 10 snake bites are going to be fatal and you can bankrupt your family, you might hesitate,” Lewin said.

Currently, antivenom is the only cure for snake bites and a single vial can cost up to $3,000, with most people needing anywhere from four-to-20 vials at a time. The treatment Lewin and his team are developing, however, could be available for just a few dollars per dose.

Antivenom is an extremely complicated chemical solution, according to Lewin, and it has many drawbacks, including a high rate of allergic reaction, a 90-minute dissolving period and a need for a doctor with precise expertise who can handle the dangerous antivenom. The compound also needs to be stored in a refrigerated area, which makes it perishable and difficult to transport.

This treatment was first introduced in the 1980s by French physician Albert Calmette, and the lengthy and complicated production process has remained nearly unchanged.

Lewin, however, hopes his low-cost buffer will increase the chance of survival for victims of snakebite.

Currently confidential and patent-pending, the treatment will most likely come in liquid form so that victims of snakebite can easily drink it, even if they are partially paralyzed, said Lewin.

“Right now, you’ve got a first aid element [to the project], which is that when you are bitten, you can drink [the compound] and make it to the hospital before having to decide whether to undergo antivenom treatment or not. The hope is that it will be able to replace antivenom entirely,” Lewin said.

Three out of four snake-related human fatalities occur outside of the hospital, according to Lewin.

“If you make it to the hospital you’re going to probably live, even without a good antivenom, because of the intensive care capabilities of most hospitals,” Lewin said. “The goal of the project right now is to provide a bridge to survival. ”

According to Lewin, current snakebite treatment does not address the problem soon enough. Lewin said that he is focusing his treatment on the first six to 12-hours following the bite because that is the immediate life threatening period.

“The first project I really want to focus my attention on is figuring out how to get the solution into a stable form and figure out a way to manufacture it. The key is to manufacture it so that it is usable in an emergency,” Lewin said.

[vimeo id=”https://vimeo.com/153864362″]

Lewin said the idea of a simple, durable compound that could counteract venom has been “floating around” in his mind for years.

“I had given up on the idea for a while, for a variety of reasons,” Lewin said. “I was actually at a party somebody had dragged me to and Jerry Harrison was there, from the ‘Talking Heads’ and he said ‘Does anybody have any crazy ideas.’ And I blurted out this idea, ‘nasal spray for snakebites.’ And he said I should really pursue this.”

Lewin’s team is very small and primarily local, consisting of Dr. Philip Bickler from UCSF and Dr. Stephen Samuel from the National Health Service in the United Kingdom, who is from Tamil Nadu, a densely populated venomous snake region in southern India.

“It is a multi-person effort. To have an idea that can save lives is great, and [it’s] why I went into medicine,” Lewin said. “From a professional standpoint, it feels as though I am finally living up to my potential, after floundering for a decade.”

Lewin said his greatest challenge has been a lack of funding among potential supporters.

“At the beginning, there wasn’t much I could tell [potential investors] other than, ‘I’ve got this,’” Lewin said.

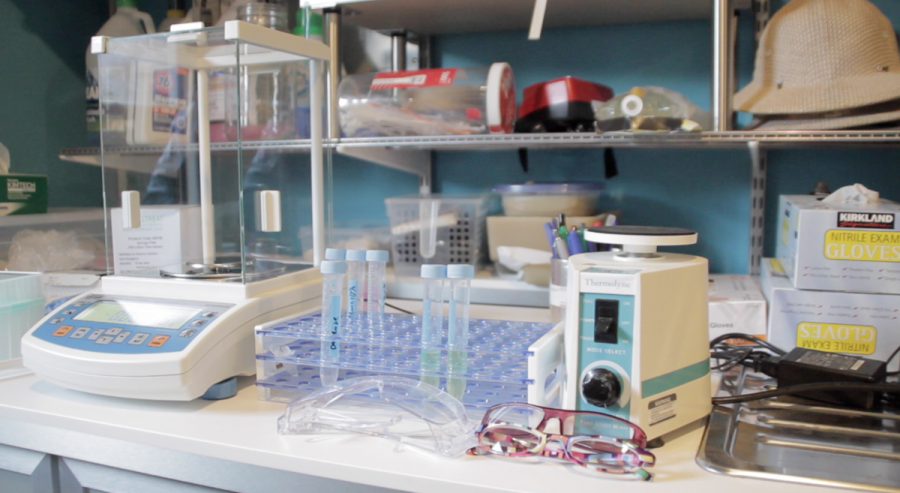

To minimize costs, Lewin has conducted a large portion of his research and tests in his own garage, which contains a small lab he built with the help of his 9-year-old son, Daniel.

“What I do in here is basic pharmaceutical formulation, basically stuff you can do without a permit,” Lewin said.

The Foreseeable Future

The yearly death toll from snake bites has remained constant at about 100,000 and has shown no sign of decline.

Lewin’s ultimate goal is to eliminate the need for antivenom and make snake bites a “nuisance problem” rather than a life-threatening and costly problem.

Lewin said he would like to develop the first oral antidote for a snakebite, that will take [the treatment] outside of the realm of hospital care.

Lewin hopes to administer the drug on humans within 18 to 24 months, but acknowledges that the process to develop, patent, and publicly distribute the drug will be very long.

[vimeo id=”https://vimeo.com/153863979″ align=”right”]

“What I expect to happen is that we will publish the basic recipe and many countries will probably ignore the patent and just start producing [the antidote]. And if that starts saving lives early then that is OK and it’s hard to argue with that,” Lewin said.

In six to 10 weeks, Lewin expects that the “secret sauce,” or recipe, will be made public in the form of an official and carefully edited scientific journal.

“The moment that [the paper] comes out there will be a lot of international pressure to develop it quickly and then I think that will accelerate things,” Lewin said. “We already know the drug is safe on humans because it has been tested it on 10,000 people, so we have a good sense that it can be deployed quickly.”

Though Lewin has high hopes for the future, he is currently most focused on developing the product so that it can be tested and manufactured properly.

“The reality is that on a day-to-day basis I am more worried about how I am going to dissolve this [solution]. If you can’t dissolve it, then it will be hard to give it,” Lewin said. “It’s not going to save anyone’s life if we cannot get it developed, so that is sort of the preoccupation.”

Lewin hopes the risks he has taken developing this new treatment will eventually make a difference.

“It is a fantastically exciting project. Intellectually it is really fun. It is not a crowded field,” Lewin said. “There are just a few people in the world working on this problem in a similar way. It would be fun to be the first, I would be lying if I said it isn’t. So, why not me? I put a lot on the line for it.”